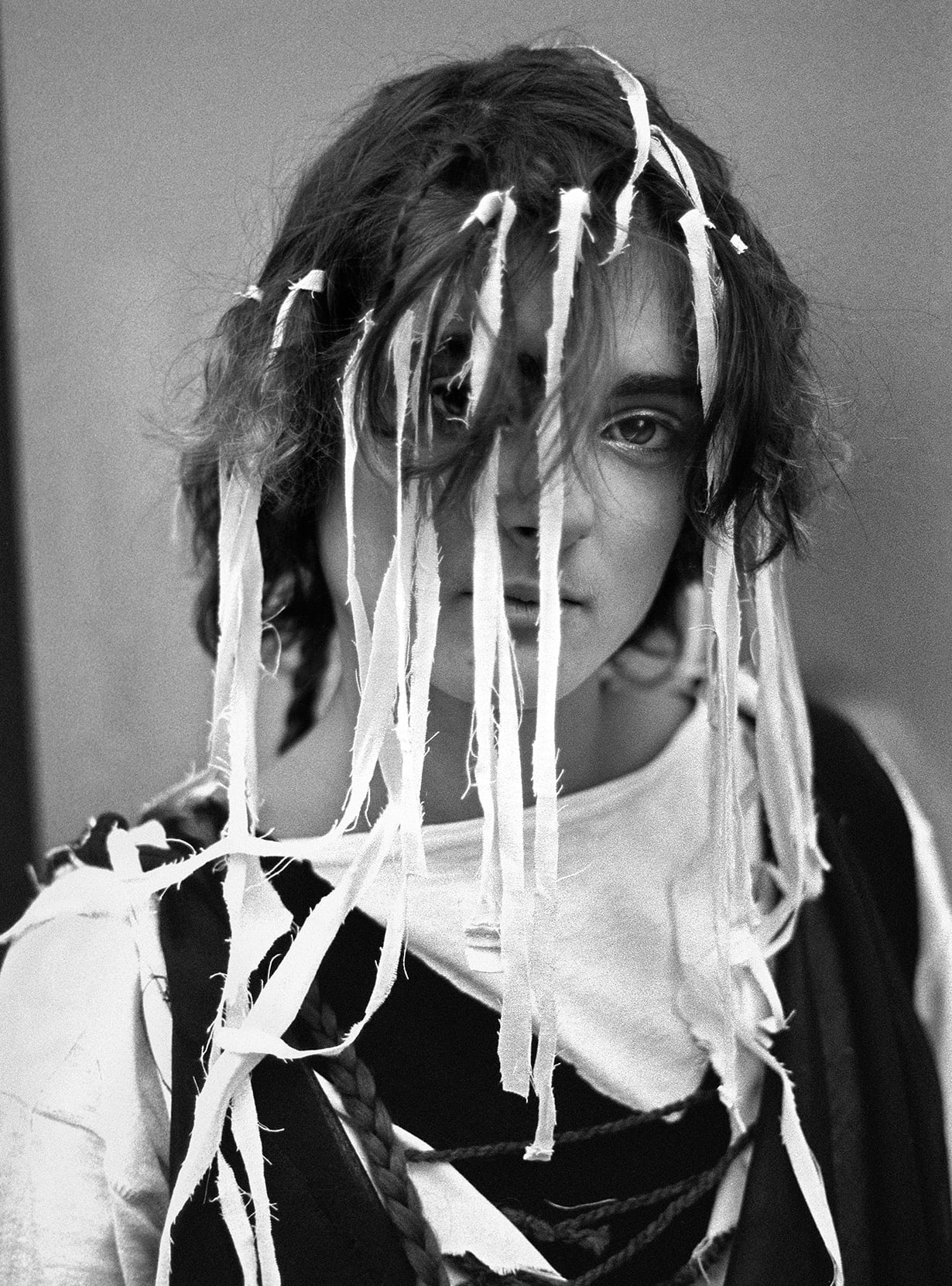

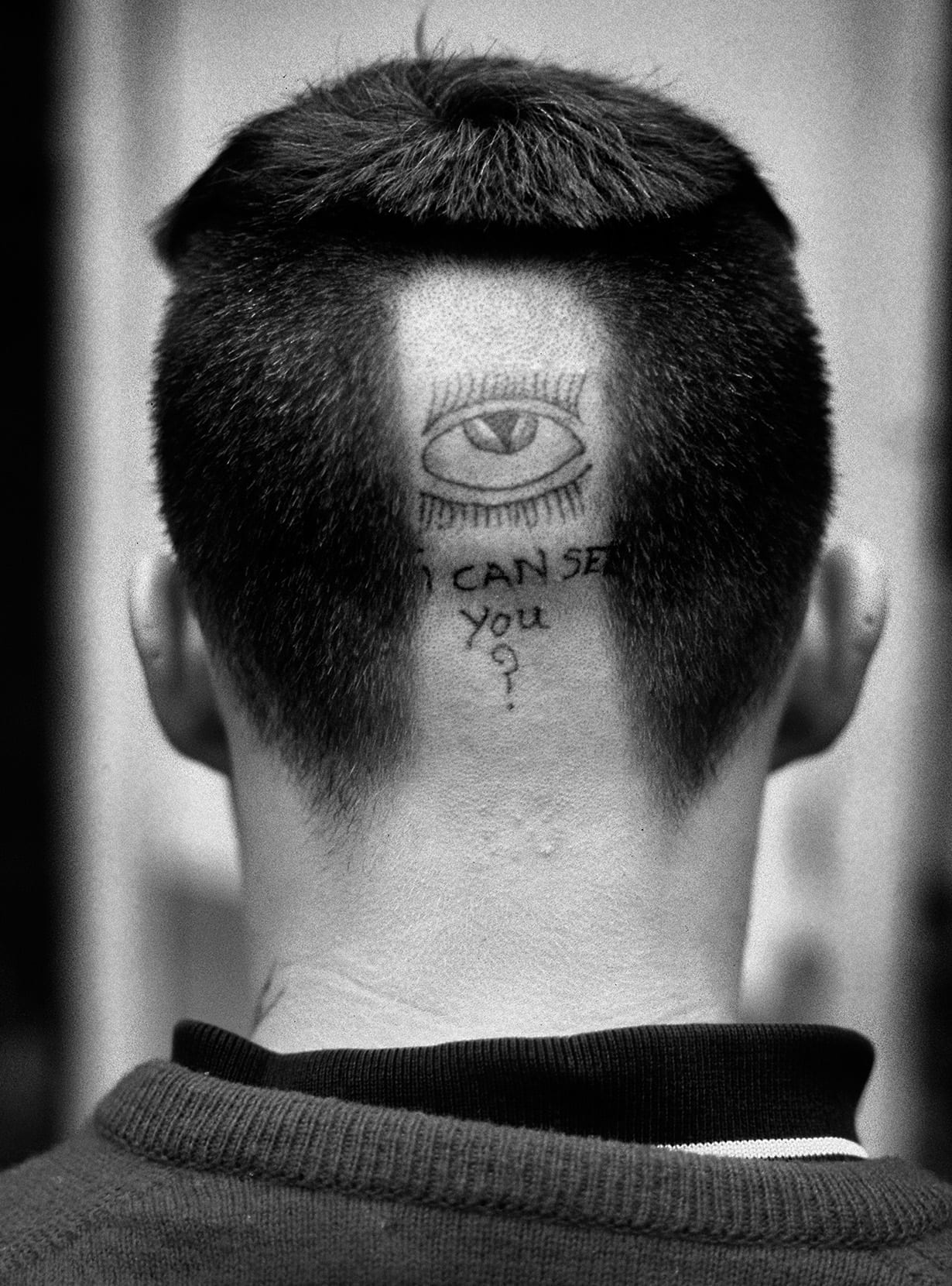

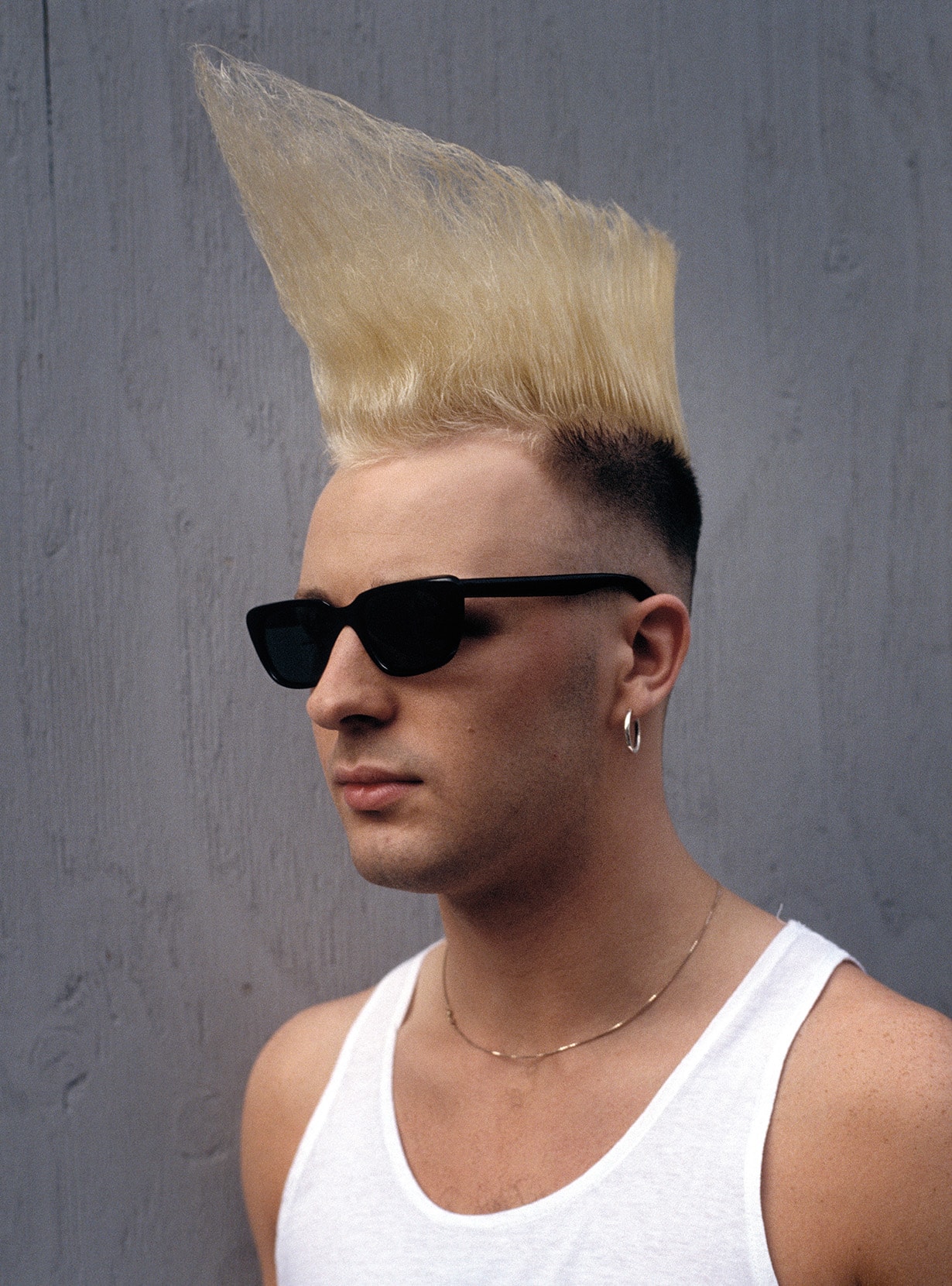

ART & CULTURE: Made In England: Derek Ridgers captures Britain’s shifting social landscape. The photographer’s extensive archive documents Britain’s subcultures, trends and anti-trends, club kids and misfits

Interview: Emma de Clercq

Images: Derek Ridgers

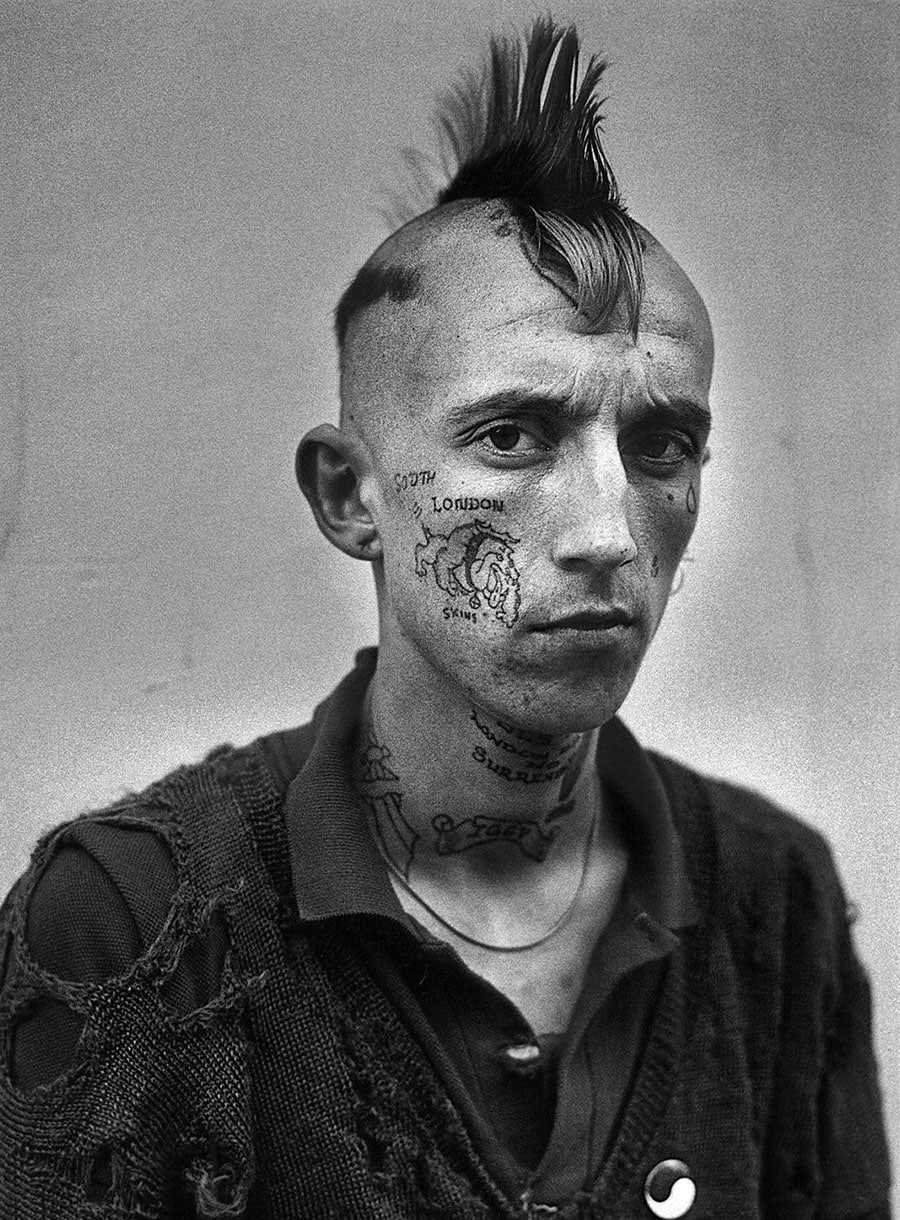

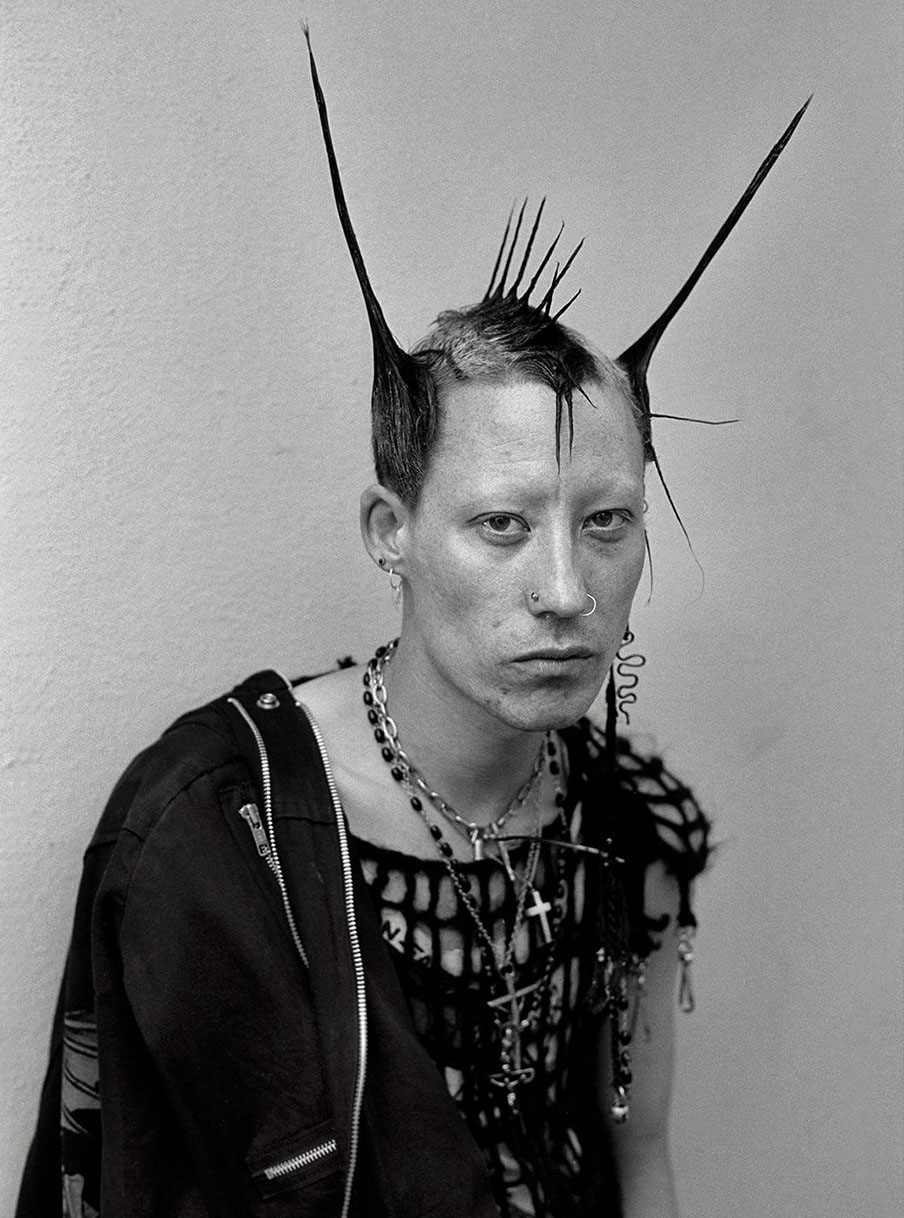

Over the course of his career, Derek Ridgers has captured thousands of faces on the streets, bars, and underground clubs of London. His photographs, a heady mix of portraiture and reportage, delve into Britain’s subcultures, its “trends and anti-trends”, club kids and misfits. Taken by Ridgers as he walked the streets of London, he would approach strangers whose anarchic looks caught his eye. In a world of bloggers and camera phones, this concept is now widely replicated. But as Ridgers states, when he first started shooting in the early 70s it was a very different story; ”it’s hard to believe now, but some of the individuals that I photographed would not have been photographed before – at all”.

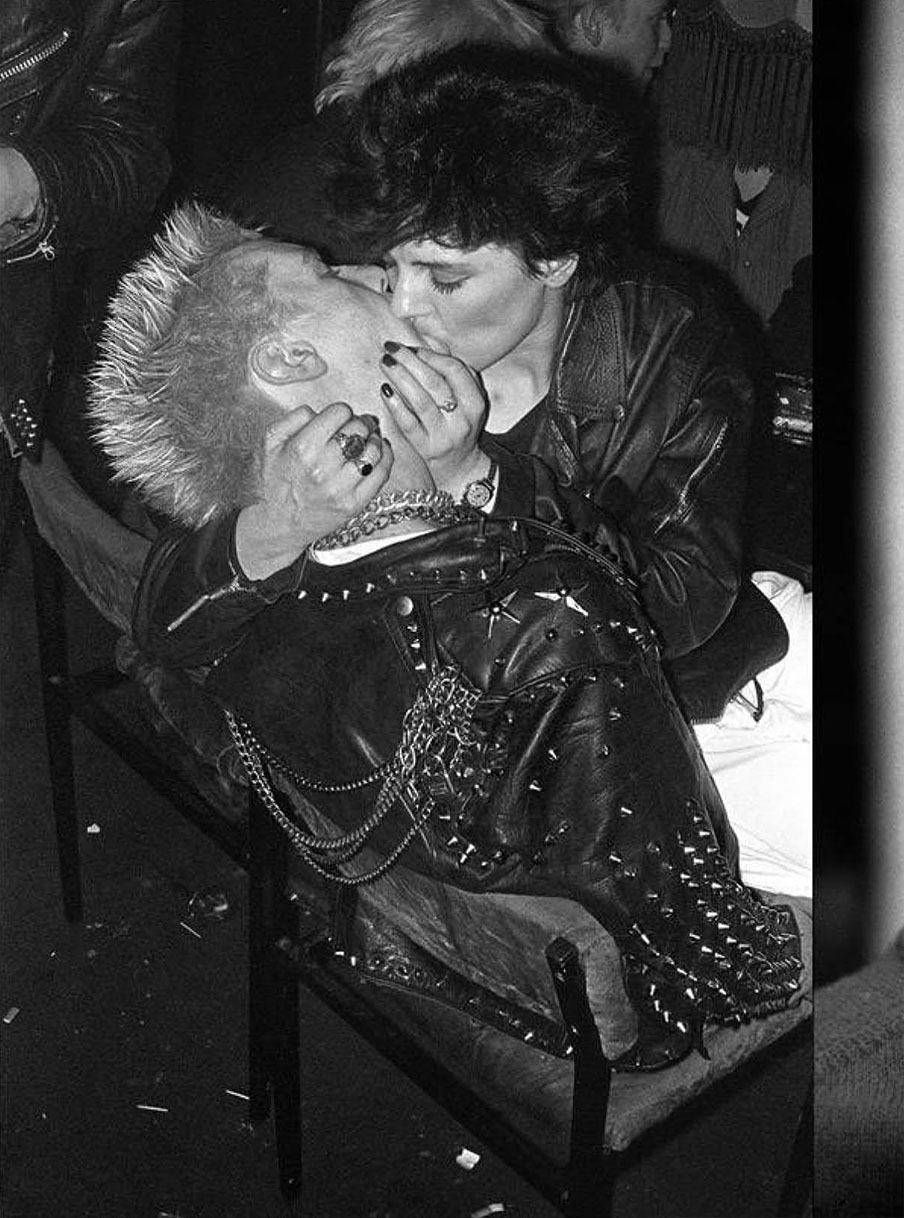

Ridgers’s photography career began when, fuelled by a love of punk music, he started to document live gigs he attended, capturing everyone from The Slits, The Clash and Siouxsie Sioux. Leaving a career in advertising to become a professional photographer, he would shoot late into the night at Soho clubs such as Billy’s and The Blitz, places which, in the eyes of today’s youth, have acquired an almost mythical status. The Blitz is regarded as the birthplace of the New Romantics movement, and was frequented by colourful young Londoners including Boy George, Steve Strange, and Leigh Bowery. But his lens did not discriminate, and while some images feature recognisable faces, most are of anonymous hedonistic partygoers, snapped on dance floors and in dark corridors, dancing, kissing, scrapping and smoking…

While there is a voyeuristic element to the images, the subject is never mocked. This is largely down to Ridgers’s unjudging gaze, his images feel like honest recordings, a world shot as seen. We spoke to Ridgers about his favourite portrait, London’s rapidly changing landscape, and what it is like to shoot in the age of the selfie.

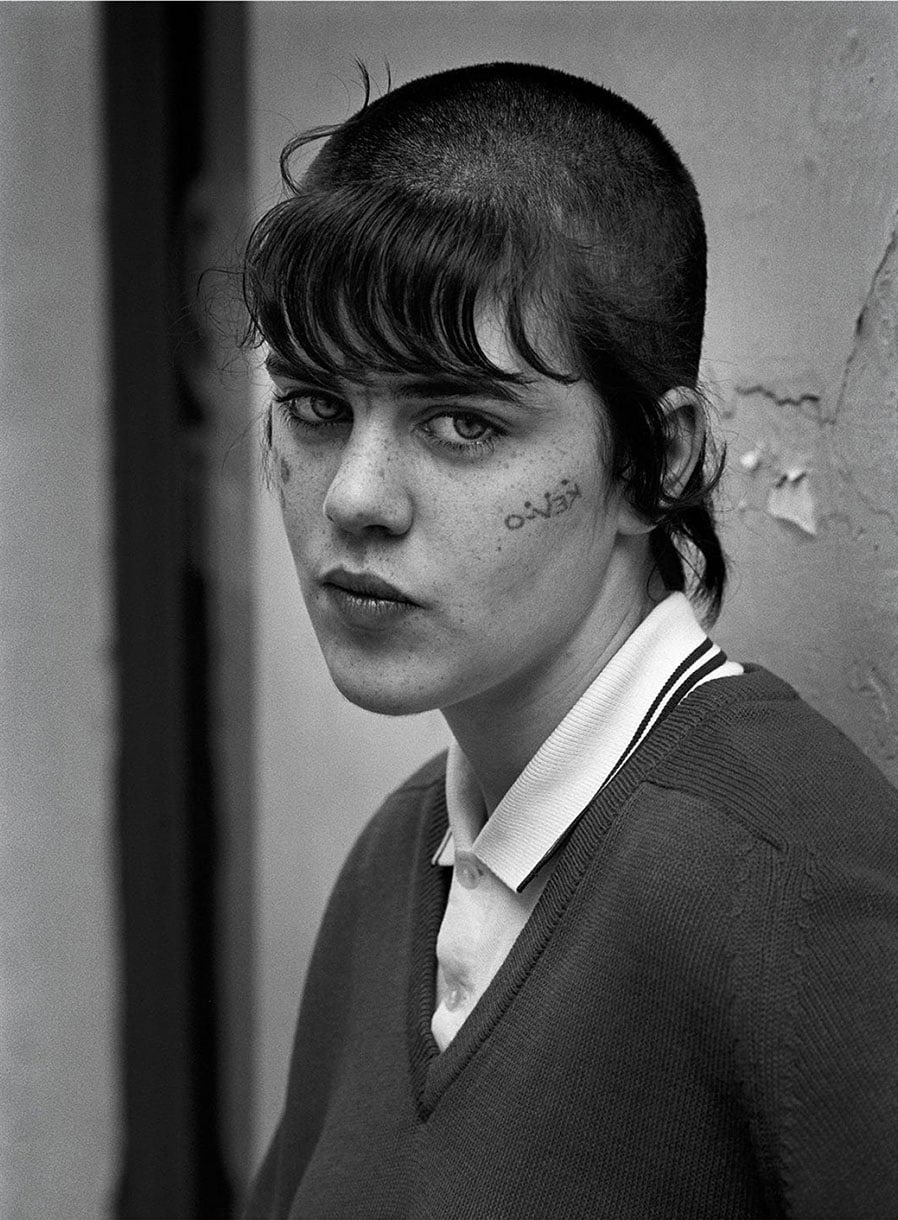

You have photographed countless individuals. Any favourites? It’s not good for me to have favourites because I don’t want to be judgmental. However, if you twist my arm… My portrait of ‘Babs’ in Soho in 1987 is one of my favourites because of her eyes. I’m not sure I ever photographed anyone before or since with eyes like that. She was a skinhead, and she was just leaning up against a wall with her dog one day, when I walked past with my camera.

"I wanted to be the kind of kid that got into fights and hung out with girls of easy virtue. But it only ever happened in my mind"

She had these big soulful, beautiful eyes and she’d tattooed a boy’s name (backwards) on one cheek. If it wasn’t for the daft tattoo, which I assume she’d done herself looking into a mirror, she would have been extremely attractive. But there was a real sadness about her. She had her whole life tattooed, roughly, on her arms. Probably all done in Borstal or similar. Babs wasn’t her real name. A good friend who had been in the same children’s home as her told me that it was Dianne.

You have documented so many different social scenes. Is there any particular group you identified with the most? To some extent, I identified with most of them. This was really why I was there, photographing them in the first place. It was a vicarious thing. I could never be a part of anything myself when I was growing up – I was a bit of a loner – but I would certainly have liked to be. I wanted to be the kind of kid that got into fights and hung out with girls of easy virtue. But it only ever happened in my mind.

The only group I ever felt a greater affinity to was the skinheads. My social and political views were diametrically opposed to those of the skinheads. Socially and politically I’ve always really been a hippy. But being a skinhead is the absolute perfect place for a social misfit – which I must admit I did feel like at times, when I was young.

There has been a major shift in the interaction between photographer and subject in recent years. In the current ‘selfie’ era, documenting oneself through image has become the norm. How does the experience of photographing a stranger differ now? To do things in the way I did is much harder now. It’s hard to believe now but some of the individuals that I photographed in the late 70s and early 80s would not have been photographed before – at all. Others, just by members of their own families. So many people were flattered by the attention.

Nowadays many people photograph themselves constantly. If anyone does anything really remarkable these days, the whole world can know about it before the sun sets. The rules have all completely changed. So why do they need people like me? I’m not sure they do. When I’m out walking the streets with my camera, people assume every photograph is for Facebook or Instagram.

Also, London has changed out of all recognition. In my opinion, it’s now the most multi-cultural city in the world and some cultures just don’t seem to approve of photography. Being photographed in the street by a stranger is not acceptable. I always ask first but that doesn’t always go down well either. Several times I’ve been threatened with violence just for asking. There is a hostility now that there never was 40 years ago.

"Socially and politically I’ve always really been a hippy. But being a skinhead is the absolute perfect place for a social misfit - which I must admit I did feel like at times"

Speaking of which, some of your subjects can be seen as quite intimidating. Do you ever feel intimidated when shooting? I’m never intimidated when I’m taking photographs because the camera gives my presence a legitimacy that I wouldn’t have without it. And I can, in a sense, hide behind my camera. I’m not easily intimidated though, even without a camera. But I can be very naive. If I had known then, when I decided to spend time photographing skinheads, what I know now, I certainly wouldn’t have done it. Although the vast majority of them were fine and just young men being young men, a small number of them were more dangerous than I could ever have imagined. No one wants to hear some of the stories I’ve heard, and one certainly doesn’t want to become involved with the participants.

Many of your street portraits were taken in Soho and the Kings Road, areas which have changed significantly since the 70s. Do you still photograph in these areas, or have you found new haunts? I guess shooting in Shoreditch or Camden now there is certainly an element of what I used to find on the Kings Road and Soho. Only really an element. In the late 60s to the early 80s, Kings Road was one of the most incredible, magical places on earth. I was taken there by my first girlfriend when I was seventeen. It was full of hippie men and girls in miniskirts. On a sunny summer’s afternoon, it was almost like being in an Austin Powers film. I thought I’d died and gone to Heaven. It’s not like that these days, anything but. I suppose higher rents forced all the interesting shops and boutiques out. And with it, all the vitality of the place. There’s nowhere in London now that’s like Kings Road used to be. The same could also be said for Soho. But it’s always been something of a spiritual home for me.

What advice would you give to a young photographer starting out today? If you really want to be a photographer, don’t go to college. There are plenty of other, very good reasons to go to college or university, but anyone who wants to be a photographer can simply pick up a camera and start tomorrow. As a former art director who used to commission photography, I never cared a jot whether someone had been to college or not, only how good their work was.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR