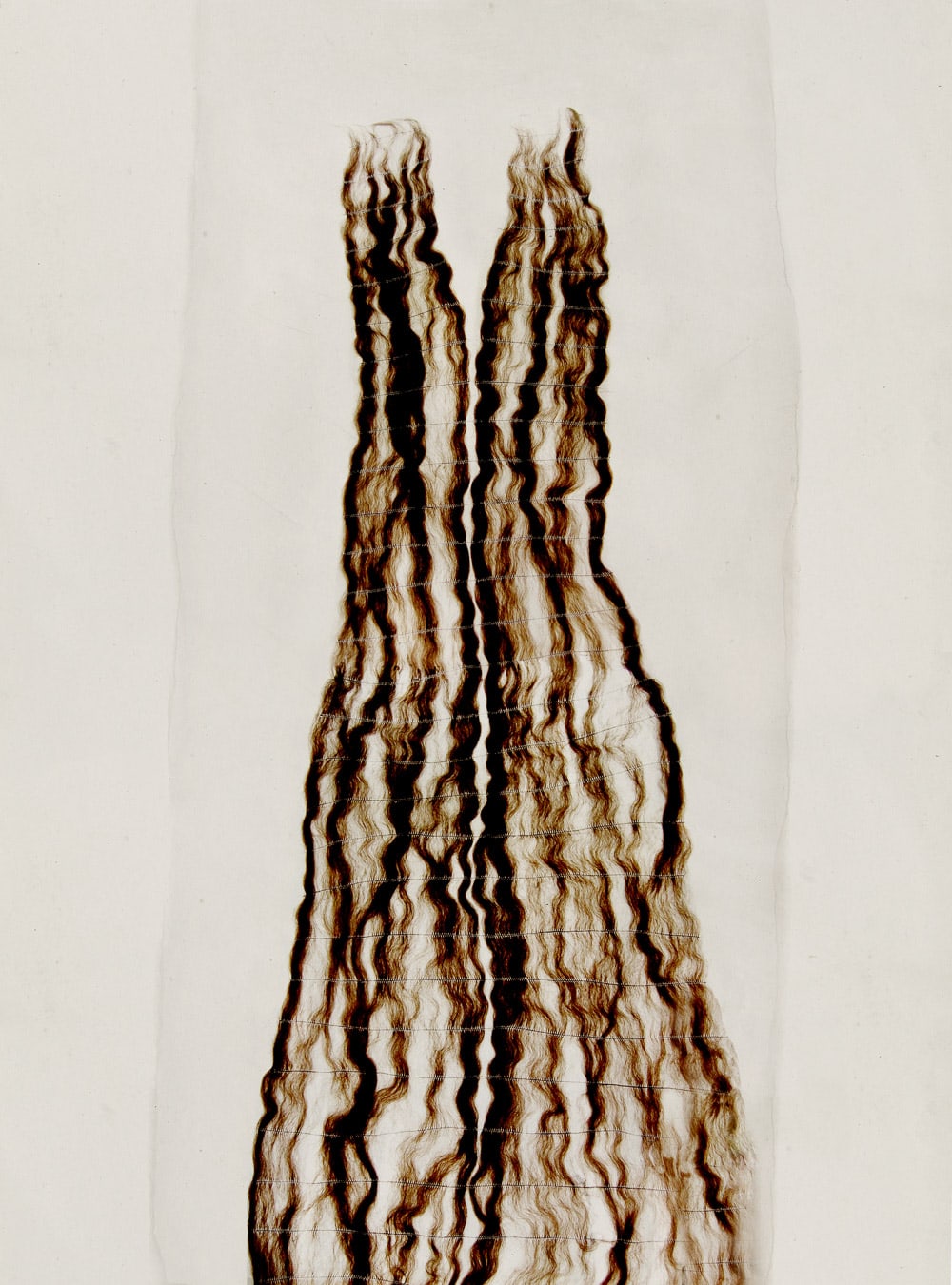

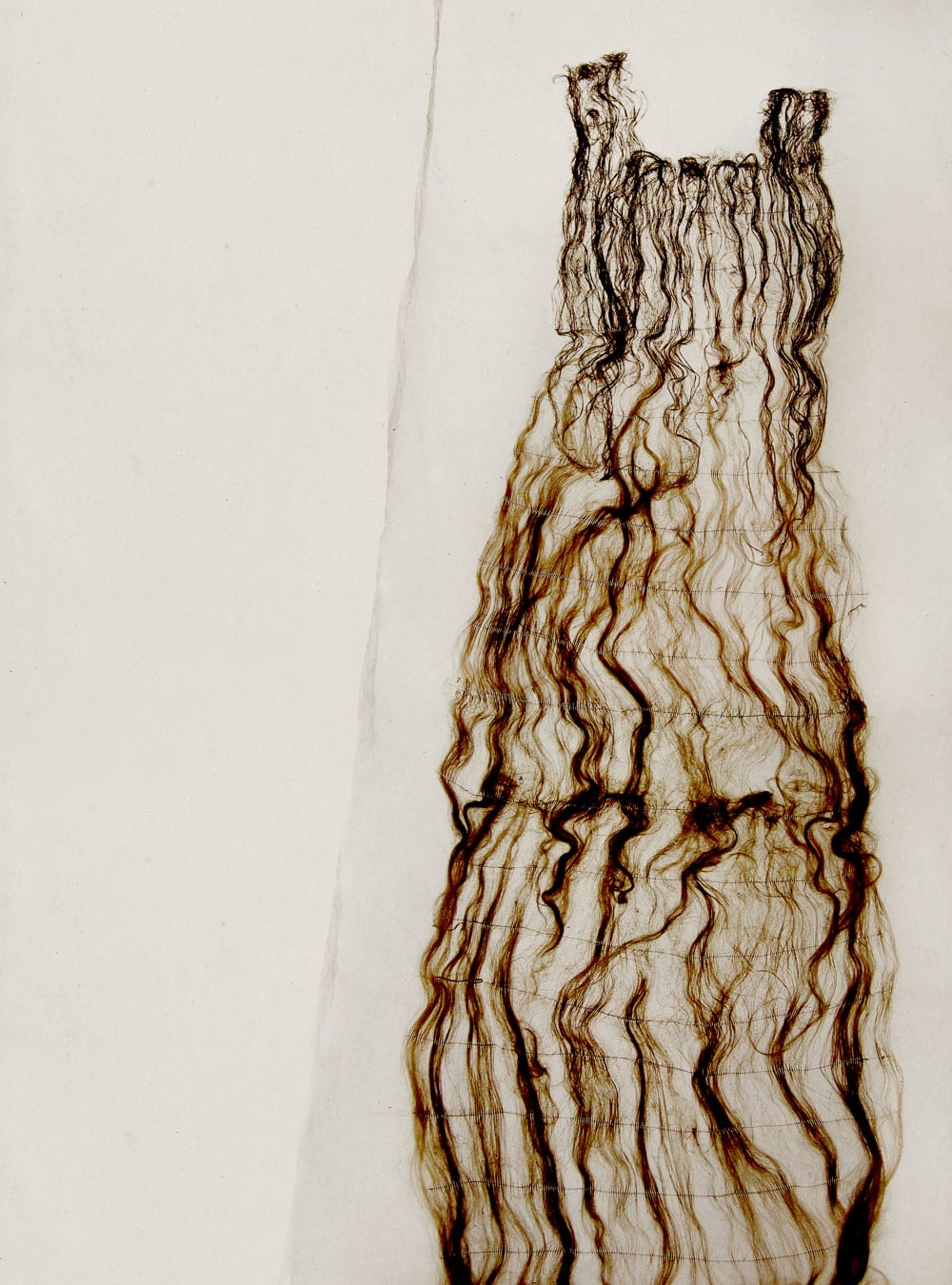

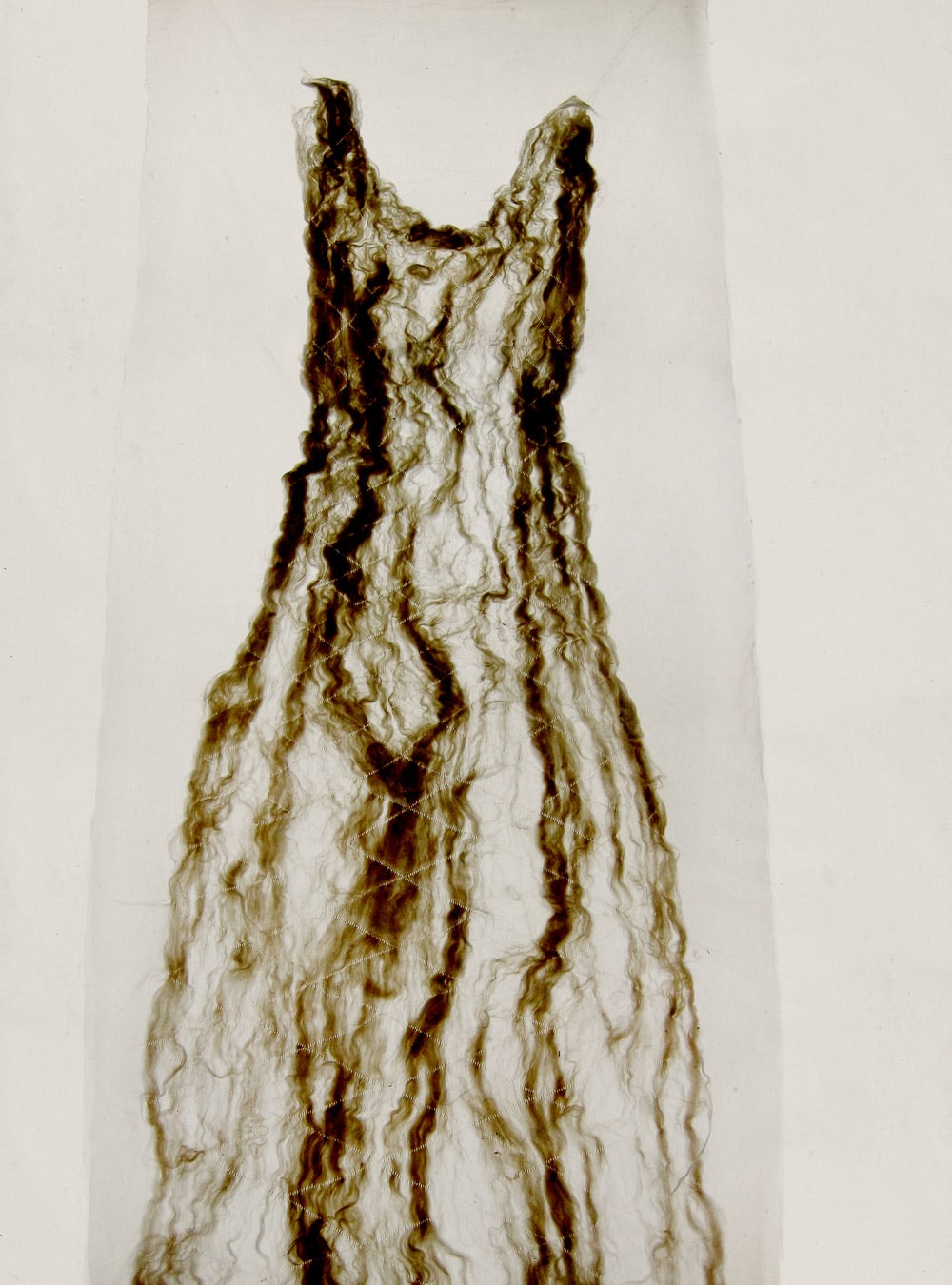

ART + CULTURE: Beatrice Oettinger, the artist behind the delicate hair dress series Raumkleider, on her enthralment with nature and the complexities of hair

Artworks: Beatrice Oettinger

Interview: Katharina Lina

Artist and designer Beatrice Oettinger’s oeuvre contains a catalogue of wearable pieces — including dresses made from hair — which, through the clever manipulation of our senses, connects the body back to nature. Amongst seas of green and flower fields which emerged once the waters had fallen, she grew up by a large, floodplain river meadow in Bavaria, Germany. Deemed unfit for agricultural use, young Oettinger wandered freely across the vast terrains, returning from her excursions with plants, fibres and other discoveries to fuel her perennial fascination with nature. “As if the meadow were the universe, the past and the now. Here the whole world took place in my small village. The meadow and its plants answered all my questions—a violet is 15 million years old.”

Bridging art and fashion Beatrice Oettinger uses natural fibres in her wearable pieces to tickle our senses and offer a glimpse into the endless pleasures of coexisting with nature. From poplar capsules that are delicately sewn into a silk shirt and slowly begin to open filling the fabric with a beautiful haze of white seed tufts, to a raw linen and wool coat with mobile scent tentacles enticing the olfactory system, transformation and sensory information are integral to her work.

"I see plants, fibres, and hair as information carriers, as living beings with their own form of consciousness and their own character"

But beyond feeding the tactile receptors, Oettinger is interested in hair as a sense in its own right: “I am convinced that hair is a sensory organ and contributes a lot to the so-called 7th sense. It’s like antennae, providing us with information about the composition of the air, subtle moods and atmospheres. They connect the inside and outside. They help us with orientation. They can perceive the finest breeze. Strands of hair spin a fine web in space that our gross senses cannot decipher. They confuse and bewitch. I have always thought that my body hair is responsible for my intuition. Or a different perspective: our body is the globe, and the hair is the forest on it.“

What first drew you to using clothing as a canvas to explore nature? I have always sewn clothes for dancing, be it belly dance, Indian dance, Bavarian folk dance. Through traditional costume tailoring in Bavaria, I came across a technique of sewing plants (rice and willow) into clothes and that’s when I started researching and experimenting. After every walk I came back with a new plant and started to work with it. So there it was again: the meadow from my childhood. I always have a meadow in front of my door — even in the city it can be on the side of the road, between the paving stones.

What was your process of working with the hair in Raumkleider? In the production there is no design, only my fingers, groping, feeling, laying, sewing. In the beginning, I have no concept in my mind. I leave the work to the hands. Fingers have their own intuition and can communicate directly with matter. They sense the surface structure, the direction, the force of gravity, the friction, and try to get a ‘grip’ on it. The greatest art is to let the hands do the work. To step back from leading with your eyes, and letting your hands do the shaping. Each material, be it fibre, hair, or seed, requires a different method, a new sewing technique and its own form.

This is also a daily exercise for me. I hold materials in my hand that weigh nothing, that are partly untameable: hair and seeds don’t necessarily want to be in pockets. I learn to deal with the “nothing” in my hand. This sensitises and charges — electrostatically or electromagnetically — and can be very exhausting.

But it also changes perception. This altered perception feeds subconscious images, which then collaborate to inform the final work. A process arises where the external world of matter interacts with that inside my body. These processes are very difficult to describe with words, but I can best describe it like this: when your fingers do the work, the results get under your skin.

Besides Raumkleider, most of your works feature clothing with incorporated plants that transform the items. You also previously said that dress is the realm where transformation takes place. Can you elaborate on this? I see plants, fibres, and hair as information carriers, as living beings with their own form of consciousness and their own character, which turns out to be an ally. We can communicate with each other; I learn that through the handiwork as well as through the nose.

We breathe through our skin, and clothing is often referred to as a second skin. The perception of the body and the feelings change with each fabric. Traditional fabrics made of fibres and hair are breathable (each in their own way) i.e., they exchange with our skin: matter meets. Fibres, hairs, molecules and human skin penetrate each other. Friction creates charges. Moisture is regulated in a reciprocal cycle. A climate of its own is created. Mixing occurs, information is exchanged. Inside and outside communicate and breathe. This is transformation: we are penetrated by the world, we become part of the world.

You slip into a dress and transform, it’s always like that. I want to make the experience and the difference of the materials perceptible, and take in new plants: be it the field thistle seed — the finest seed I know and one that seems to defy gravity — or the stinging nettle with its mixture of defensiveness, solidity and furriness.

"We live in times of data protection regulations and data surveillance. From the information in the hair, you can reconstruct a lot about a person's habits over the last few months. Would people choose to leave their hair to me?"

Your other works use dandelions, flowers, or fragrant beeswax, which feel whimsical, romantic and delicate. The Raumkleider dresses are as beautifully delicate as the other works, but for many, hair tends to elicit feelings of unease or disgust when it isn’t attached to a live being. What is your take on this? There are certainly as many answers to this as there are individuals. Hair has been the focus of power and magic for many millennia and there is an infinite variety of actions with hair in this superstitious context that are not rationally comprehensible. Foremost among these is the belief of gaining power over a person by possessing their hair. This belongs in the category of saliva, blood and hair.

There are a lot of emotions associated with hair that can get under your skin. An especially dark chapter in Nazism in Germany is the use of hair of murdered Jews for further processing into yarn and mattresses. I believe that much that has to do with hair is stored in the subconscious, rather than being directly comprehensible through the mind.

The fine structure and the practically difficult comprehensibility/handling, as well as the mass of hair, bring us to the limits of our need to gain control over something. This challenges not only the craft, but also the emotions (patience).

Turning plant fibres or hair into fabric may require chemical, almost alchemical, work processes that involve slippery or fermenting moistures — processes that can involve disgust. In the modern age, machines have overtaken this, and we hardly have any craft, feeling, palpating contact with these processes anymore. These archaic techniques, which I would include under the subject of art, are no longer part of our basic education.

I have noticed in my courses that many people can no longer touch natural fibres such as silk, flax, because they cause a kind of discomfort and stress in the fingers. Fingers want to comprehend. (In German “begreifen“: touch and understand.) Dealing with smooth plastics (polyester) and surfaces (cell phones) every day makes our fingers and minds believe that materiality means no resistance. But hair fibres are matter with resistance. Our fingers actually love these thousand-fold variations of information created by surface texture/haptics and friction.

Would you ever make a second series of dresses made of human hair? Or is there a specific reason why you stuck to animal hair? I like your idea! Gladly, if someone gives me the hair! I made a small series with my “baked dresses” from human hair. Anyone could send me their hair and I’d make a miniature dress from it. There was no feedback. It’s like you said: the people who saw them thought it was creepy, like there was a Wolpertinger lost in my studio.

It’s a very sensitive subject. On top of that: we live in times of data protection regulations and data surveillance. From the information in the hair, you can reconstruct a lot about a person’s habits over the last few months. Would people choose to leave their hair to me? This aspect would certainly be part of such a project.

What are your goals for the near future? In the current situation my goals are to find ways to use my knowledge and experience with plants and fabric to help change and adapt our consciousness and perspectives to the challenges ahead with climate, collaboration and creativity.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR