- Zu Kalinowska

- Zu Kalinowska

- Zu Kalinowska

ART+CULTURE: Zu Kalinowska’s hair sculptures invite us to question how we perceive intimacy, allure and discomfort in relation to humanness or its absence

Interview: Katharina Lina

Art + Director: Zu Kalinowska

Director of Photography: Julian Moser

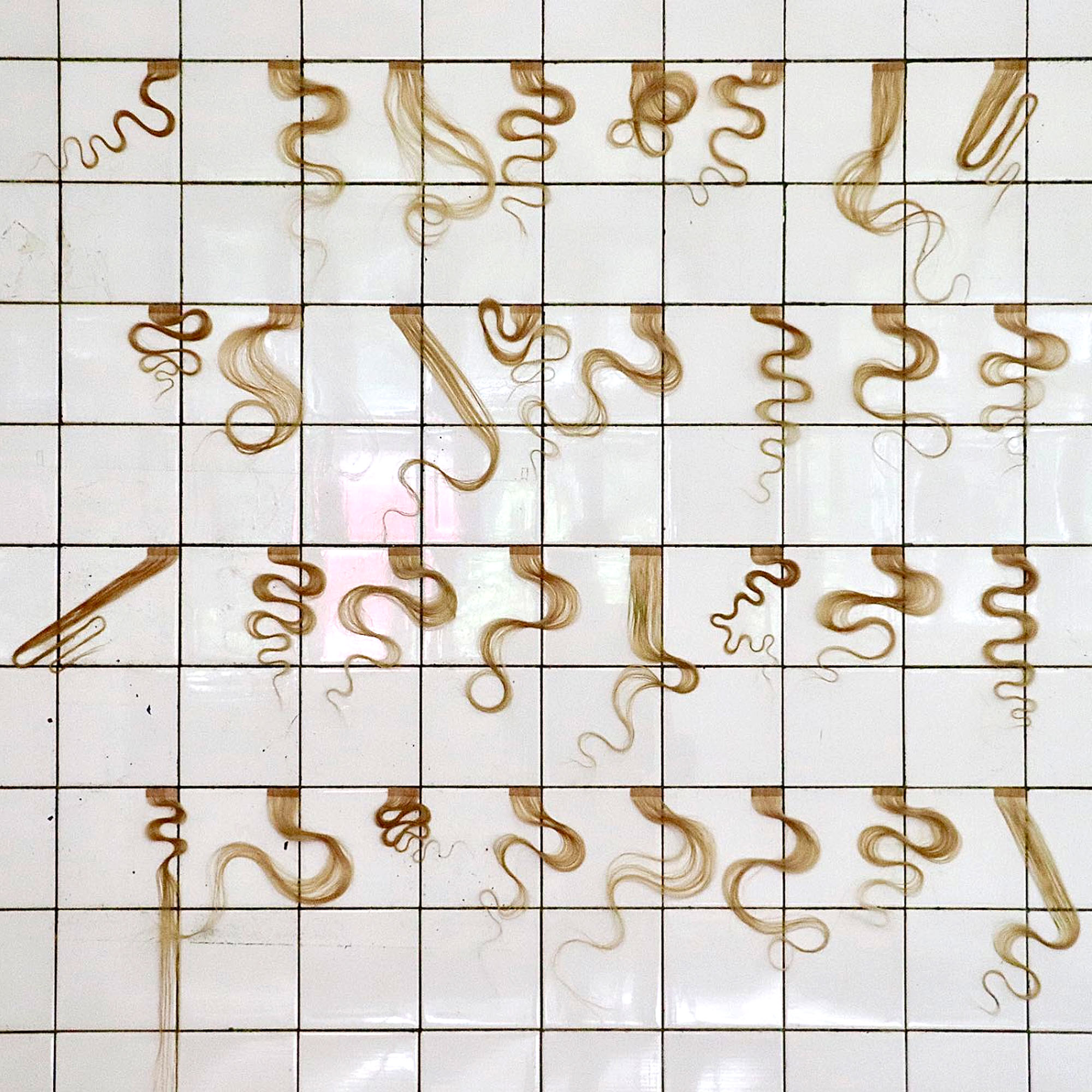

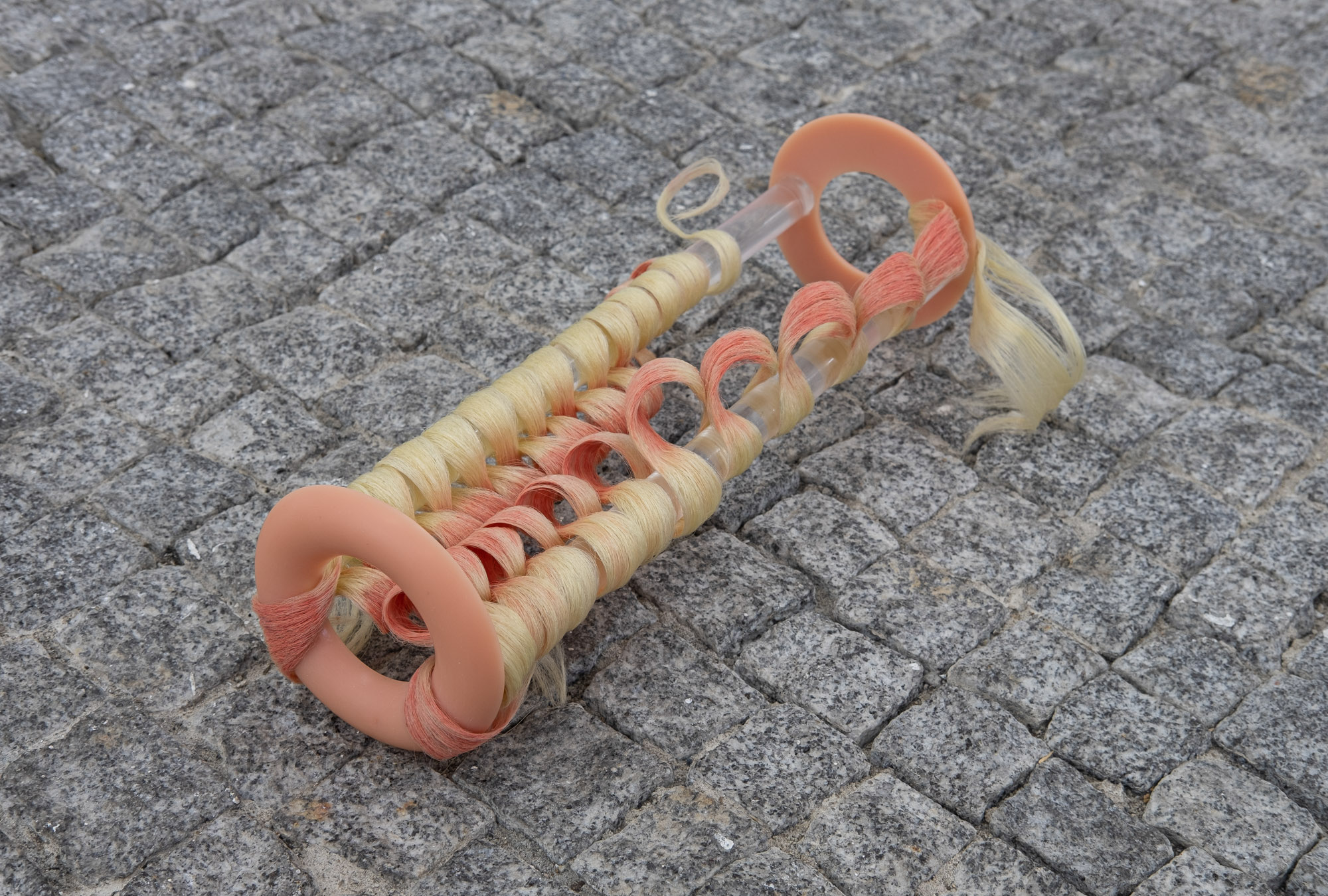

Zu Kalinowska’s work spans across sculpture and film, utilising hair to delve into our preconceptions around reality, discomfort, and intimacy. Using both human and synthetic hair, the artist/filmmaker styles the hair pieces before incorporating them into the structures of inanimate sculptural objects. Although hair is inherently dead, something about the fibre’s perceived origins at the top of our scalp breathes just enough life into the sculptures to personify them with an eeriely human touch. Kalinowska’s work examines the contrast between the humanness conveyed by hair against the unique material properties of the strand as they reveal themselves when disconnected from human meaning. Unravelling the psychosocial aspects of hair also allows the work an independence, a “purpose and intent in post-human hair worlds.” What does it say about being human when our hair can express feeling, travel, twist and twine… without us?

You’ve worked with hair across different media like sculpture and film. When does one medium lend itself better to hair than another? The flatness of film hides imperfection much better than sculpture. I try to play with reality, and question what is real and what is fake. Film lends itself to this playful questioning, because of the nature of its surface. It makes those value judgements harder to call, between constructed ideas of reality or falsehood.

"By removing the human and giving these objects their own life, it makes it harder for us to know how we feel about the materials and the work"

Why are you drawn to working with hair? My artistic interests lie between what we view as ‘real’ and ‘fake’, and combining those to make new worlds and possibilities. Hair comes with so much cultural baggage. It is public and private at the same time, internal and and external. It is a bridge between different worlds. It is deeply personal and yet also a method of communication and control. I’ve never been very interested in hairdressing or styling my own hair. When I use hair in my work, I try to disregard the human form in a traditional sense. I find ways of taming and controlling hair as a sculptural form. By removing this human element, hair reveals an identity as a material and as a meaning, with its own difficulties and challenges to work with. It can be very difficult for us to unlearn our attachments to hair as a human construct. But by physically disconnecting hair from the human form – and translating it as sculpture – it becomes easier for me to question what it means for society. I’m fascinated by the value judgements we place on hair. Where hair is or isn’t. How we make these decisions, and react so strongly when our expectations aren’t met.

What do you like and dislike about working with hair as a medium? I both like and dislike the same thing… the challenge to control it, or bend it to my will – working with so many individual strands and trying to make them one form. In this way, the process of working with hair also mirrors society.

Your film for Berlin’s contemporary music month 2018 is mesmerisingly surreal. What kind of brief were you given? I was very fortunate to have trust from them. I used this creative freedom to invest these hair-sculptures with agency. I wanted to create an eerie journey, of the hair crossing between two worlds. And I wanted to give the material purpose and intent, in these post-human hair worlds. The hairs use an orifice portal to travel between realms. I tried to make something that is satisfying to watch, but also gives an uneasy feeling that’s hard to define. By removing the human and giving these objects their own life, it makes it harder for us to know how we feel about the materials and the work. Suddenly we don’t really know if it’s dark or light.

"I both like and dislike the challenge to control [hair], or bend it to my will - working with so many individual strands and trying to make them one form. In this way, the process of working with hair also mirrors society"

Could you tell us a bit about your thought process behind this blue piece? I wanted to express and make something that is familiar to the way we’re physically structured, but also becomes something past that. The work becomes some sort of new being – that has memories of the human, but has mutated and evolved beyond us.

Give us an insight into your process for preparing hair to work with. Do you dye it yourself? I work with a mix of human and synthetic hair, and a mix of new and retired human extensions. I enjoy experimenting with different methods of dyeing. Part of the fun for me is trying out different inks, pigments and paints, to see the potential outcomes – often with nice surprises along the way. And I’m a sucker for gradients. I really love exploring and combining materials, and a lot of my process comes from that learning. I get a lot out of seeing how far I can push an idea through the process. And I often get sidetracked by discovering properties of the hair I hadn’t planned, and consider these smaller works as sketches. So ultimately my approach is a bit of a mix… sometimes I dye it and sometimes I buy pre-mades, according to the needs of each material and project. The making of these sculptures needs so much touching; sanding, rubbing, caressing, washing and sanding again. I often ask myself it’s possible to transpose intimacy into an object, and if that intimacy can then be felt by the viewer.

Ideally, what do you hope an audience takes away from your work? To come away looking at hair a bit differently. What is hair without a human? Also questioning what is real or fake – and does it matter, the difference between synthetic and real? I like to make work that is uncomfortable, that the viewer isn’t sure if they like or not. Because it plays on social preconceptions, and subverts our emotional or psychological triggers. I’m also trying to leave them with some connection. I want to express intimacy with the viewer through my work – though at a safe distance, that allows space for surprising directions and new interpretations.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR