ART + CULTURE: Designer Mijoda Dajomi’s debut headwear collection dreams up a sisterhood of rain gatherers in a water-scarce future

Designer: Mijoda Dajomi

Photography: Mijoda Dajomi + Cassia Agyeman

Interview: Hasadri Freeman

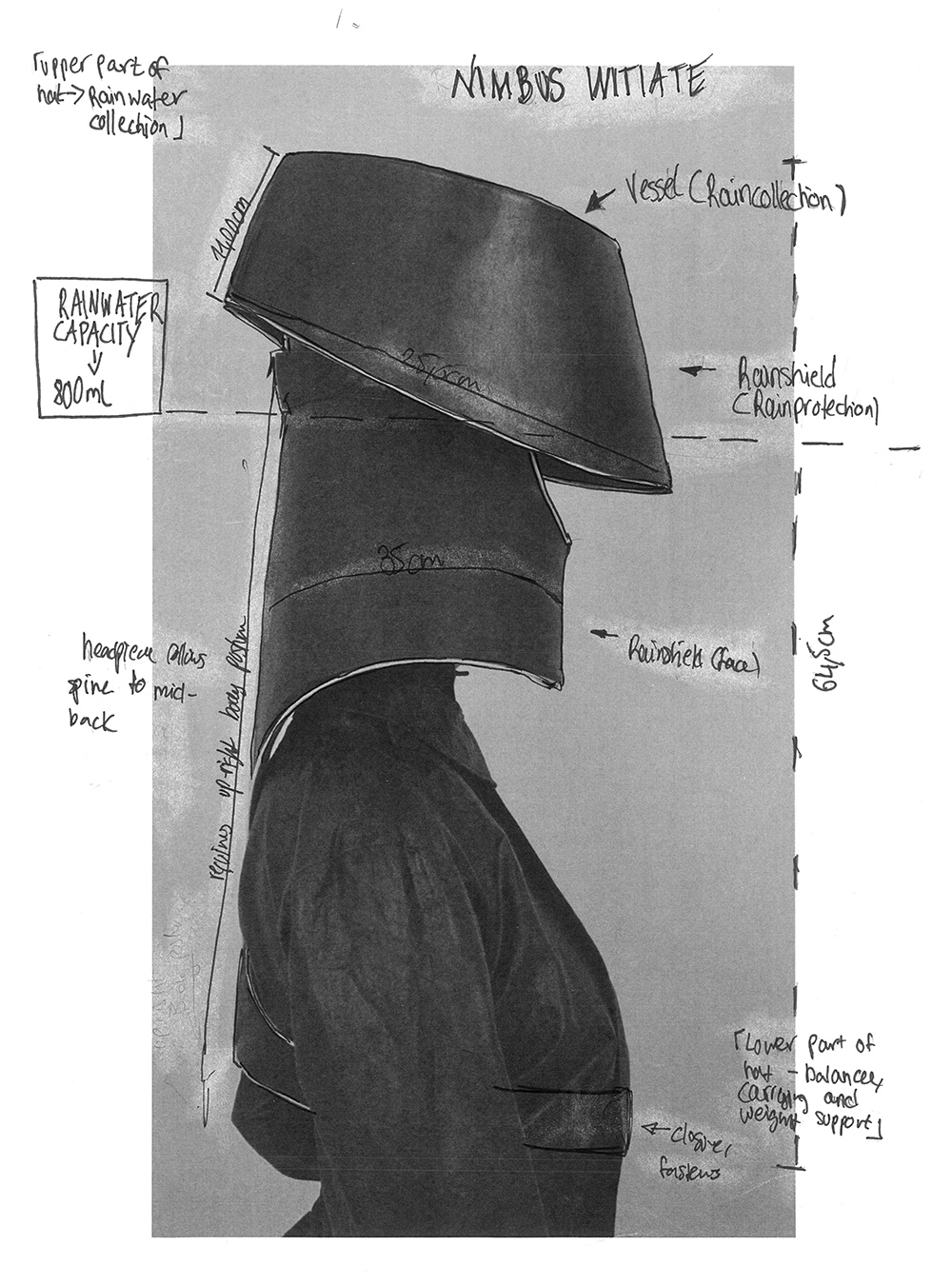

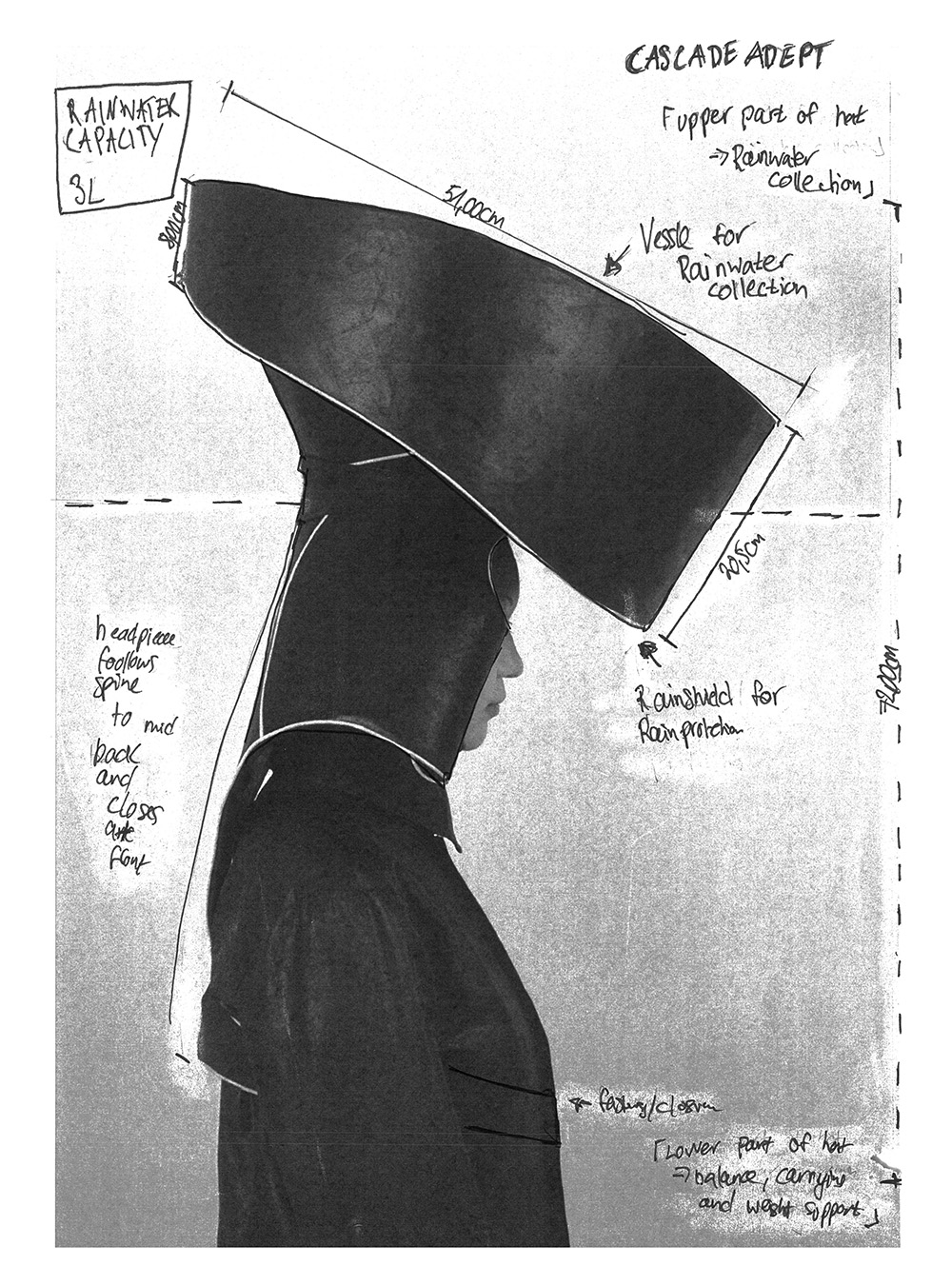

Mijoda Dajomi is, like so many young designers responding to the changing circumstances in which their material medium operates, asking her designs to do two things at once. For a generation of designers who have never experienced a world without climate crisis headlines, there are very real questions at play about the utility and function of fashion in a resource-scarce landscape. So for her MA headwear design collection, Mijoda Dajomi crafted the uniforms of a fictional group of women living in a not-so distant future where water is a precious commodity. These women, the ‘Daughters of Rain,’ have devoted their lives to planetary stewardship as guardians of water. Their headwear, which in the designer’s own words “function somewhat like a backpack for the head,” collect precious rainwater in increments anywhere from 800 millilitres, to 5 litres, dependent on the individual wearer’s rank within this female-only collective. We got to chat to the designer about the interplay of utilitarian fashion and female-led ecological stewardship in her collection, as well as the role of institutions and competitions in supporting emerging designers, why she’s not too concerned about social media, and the narrative power of design.

Tell us a bit about yourself and how your interest in millinery/headwear design developed. I’m of German and Togolese descent, and I currently live in London. I began creating hats in 2020, towards the end of my undergraduate studies in fashion design. It was initially a hobby—exploring various techniques and materials, while also participating in internships and workshops to expand my knowledge and skills. I only moved to London from Berlin in 2022, after receiving a scholarship for the MA Fashion Artefact course at the London College of Fashion, and it was during this course that I developed a purposeful direction in headwear design. It feels like the perfect fit for me, as it combines my skills as a maker with a refined design language and my background in fashion.

Your latest collection, ‘Daughters of Rain,’ has a particular use case for a water-scarce future. Walk us through the effect that the climate crisis has had on your design practice and on your outlook as an artist. Fashion design has traditionally been a tool for self-expression, but in the context of the climate crisis, I wanted to explore how it could also be socially responsive and innovative. ‘Daughters of Rain’ is a speculative exploration of a future where water scarcity becomes a pressing global issue, imagining how society might evolve in response to environmental challenges. It envisions rain becoming so vital that whenever it falls, people gather outside, eager to capture every single drop—using any means possible, even through what they wear on their bodies. This collection is my attempt to explore how fashion design can adapt to new realities, turning a potential crisis into a space for creative action and meaningful dialogue.

Could you tell us about the background of the collection’s title? What do you hope audiences infer from you drawing a relationship between female collectives and a sustainable future? Daughters of Rain isn’t solely a headwear collection, but a fictional narrative about a visionary society founded in response to the escalating water crisis of 2085. I imagined the Daughters of Rain as a collective of women driven by a mission rooted in environmental stewardship, dedicated to the collection and preservation of rainwater to help and support society through the crisis of water scarcity.

The concept and design aesthetics of Daughters of Rain are inspired by lay sisters and their devotion, heroism, solidarity, and acts of charity during times of crisis. These women embodied the mission of their orders, uniting groups of women across the globe and throughout history in a common, creative purpose. While lay sisters dedicate themselves to religious service, the Daughters of Rain commit themselves to the stewardship of water. My narrative envisions them as key advocates in shaping a more sustainable, resilient, and harmonious relationship between humanity and water, as guardians of rain’s embrace.

Much like in film or costume design, I’ve created a character for each hat; each piece embodies a unique identity. For instance, the hat called Torrent Guardians, represents the Daughters with the highest rank within the society. This is visible through the height and dimensions of the hat, as well as the amount of water they can collect: up to 5 litres.

I’m sure your work has drawn comparisons to abayas or niqabs, though the religious iconography of veiling/covering parts of the female body and face is not at all limited to Islamic practice, and in fact in your collection, is more related to Christian practices. What role do culturally specific perceptions of femininity in general play in your designs? So far, no one has made a comparison to abayas or niqabs. However, I do often get compared to the costume design in Frank Herbert’s Dune!* My headpieces are indeed designed to cover and shield parts of the face, but from a fully functional perspective. The ‘covering’ or ‘veiling’ is intended to protect and shield from rain and wind while collecting rainwater outside in nature. I refer to this part of the hat as the ‘Rainshield.’ Even the clothes they wear are designed to keep them dry while collecting rain, and therefore cover most of the body.

Since the concept draws inspiration from the ‘Lay Sisters,’ who are known for covering and concealing their bodies for spiritual reasons, there is certainly a connection—but I have to admit this happened organically rather than intentionally.

My work is fictional and set in a speculative future, so it doesn’t directly reflect the cultural perceptions of femininity in today’s world. For this project, I did not specifically consider those cultural ideas. While the narrative does draw inspiration from historical practices, it exists within a fictional future context, removed from specific cultural and societal perceptions of femininity that we have in today’s world.

*Editorial note: Dune as a work draws heavily on Islam and the Middle East as influences.

Your practice as a whole constructs shapes far in excess of the normative head shape—who inspires you to push your designs far beyond traditional millinery silhouettes? I can’t exactly pinpoint what inspired me to push and shape my work into what it has become. It was probably mostly my own motivation and drive. I don’t define myself as a milliner, but as a fashion designer who specialises in headwear design. I think this perspective gives me more freedom to push boundaries within that discipline.

From a logistical perspective, the size and height of each of my rainwater collector hats are based on specific reasoning. The hats are designed with a particular purpose in mind: the collection, storage, and carrying of rainwater while being worn. The height, starting from the forehead upwards, determines the size of the vessel or funnel where the rainwater is collected. The taller or larger this section is, the more rainwater it can gather. The part extending from the back of the head down to the middle of the back is responsible for balancing, carrying, and distributing the weight of the collected water. The whole system functions somewhat like a backpack for the head.

Your headpieces often obscure the face, at least partially. What does ‘the face’ mean to you as a designer? What do you hope to achieve with designs that sculpt ‘the face,’ and to an extent, individual identity, in this way? For me, the face, regardless of its individual features, offers a glimpse into a person’s identity, and headwear has the ability to either underline personality through intentional expression or to obscure parts of the face, creating space for interpretation and an aura of mystery and anonymity.

For the Daughters of Rain, the headpieces serve not only a functional purpose but also a symbolic one. Each design reflects the wearer’s rank within the society: the larger the hat, the higher the position. This is a common practice for identifying a person’s status or role within a group or realm. In this context, my headpieces significantly contribute to the wearer’s identity within the society of my fictional narrative.

What role do you feel institutions and competitions can play in supporting young artists, and what feels obsolete? In what creative spaces have you felt the most supported? For me, institutions can play an important role in the journey of young designers, but they’re not essential for everyone. I’ve honed my skills through determination, but without attending a fashion design school, I wouldn’t have discovered my talents or developed my skills to the level I’m at today. It wasn’t just the technical training — it also shaped my design sensibilities and refined my eye for aesthetics. I believe that young artists and designers who wish to pursue a career in a creative field but lack connections or a background in it should definitely consider going to an institution, as it can provide invaluable opportunities and experiences. I also really enjoyed my time at LCF because I knew exactly what I hoped to achieve. I remember I brought in about 20 different handmade samples for my first tutorial, which, looking back, was a bit crazy—the average is usually around 4. But I knew I wanted to make the most out of this MA to carve my path as a designer, and I do think I succeeded. I managed to create something new and purposeful, and that makes me proud.

So far I’ve won a scholarship, two awards, a sponsorship, and I’m currently a finalist in the ITS 2025 Contest, which will take place in March. These competitions, especially for graduates looking to continue developing their practice, are in my opinion incredibly important. I developed my collection to propel me to the next step, so it doesn’t resonate with me to spend years and months on a project just to trade it for a graduate certificate. I’d recommend any recent graduate designer, artist, or maker to apply to as many competitions as possible—they offer significant opportunities for growth and exposure.

For the Daughters of Rain, the headpieces serve not only a functional purpose but also a symbolic one. Each design reflects the wearer’s rank within the society: the larger the hat, the higher the position. This is a common practice for identifying a person’s status or role within a group or realm. In this context, my headpieces significantly contribute to the wearer’s identity within the society of my fictional narrative.

Social media is always encouraged for young designers, but views are changing as algorithms and technocrats alike begin to suppress voices outside the mainstream. What role has social media played in building your brand? Social media is definitely a crucial tool for building a brand these days. I only started using it as a promotional tool around August of last year, and it’s true that growing organically has become much harder. It often feels like everyone is focused on growth, regardless of content or purpose—and honestly, it sometimes seems like if people could follow themselves, they’d do so in triple action!

The current creative climate for young designers is largely driven by the demand for innovation and sustainability, with much of the conversation happening online through social media platforms and magazines. It’s excellent how these platforms provide access and exposure, allowing designers to gain recognition quickly and effectively. However, this has also resulted in an overwhelming flood of creative output, making it increasingly difficult to stand out in an overstimulated landscape. The constant stream of content can be both energising and exhausting, as everyone strives to be seen and heard.

For me, as an emerging designer, the best way to gain recognition from an authentic audience is through features, collaborations, and participating in events and gatherings. Eventually, everything will fall into place.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR