ART + CULTURE: Through a series of hairstyles, photographer Céline Bodin explores “female types” and our associative minds

Photography: Céline Bodin

Hair: Kim Rance

Makeup: Lucy Joan Pearson

Interview: Katharina Lina

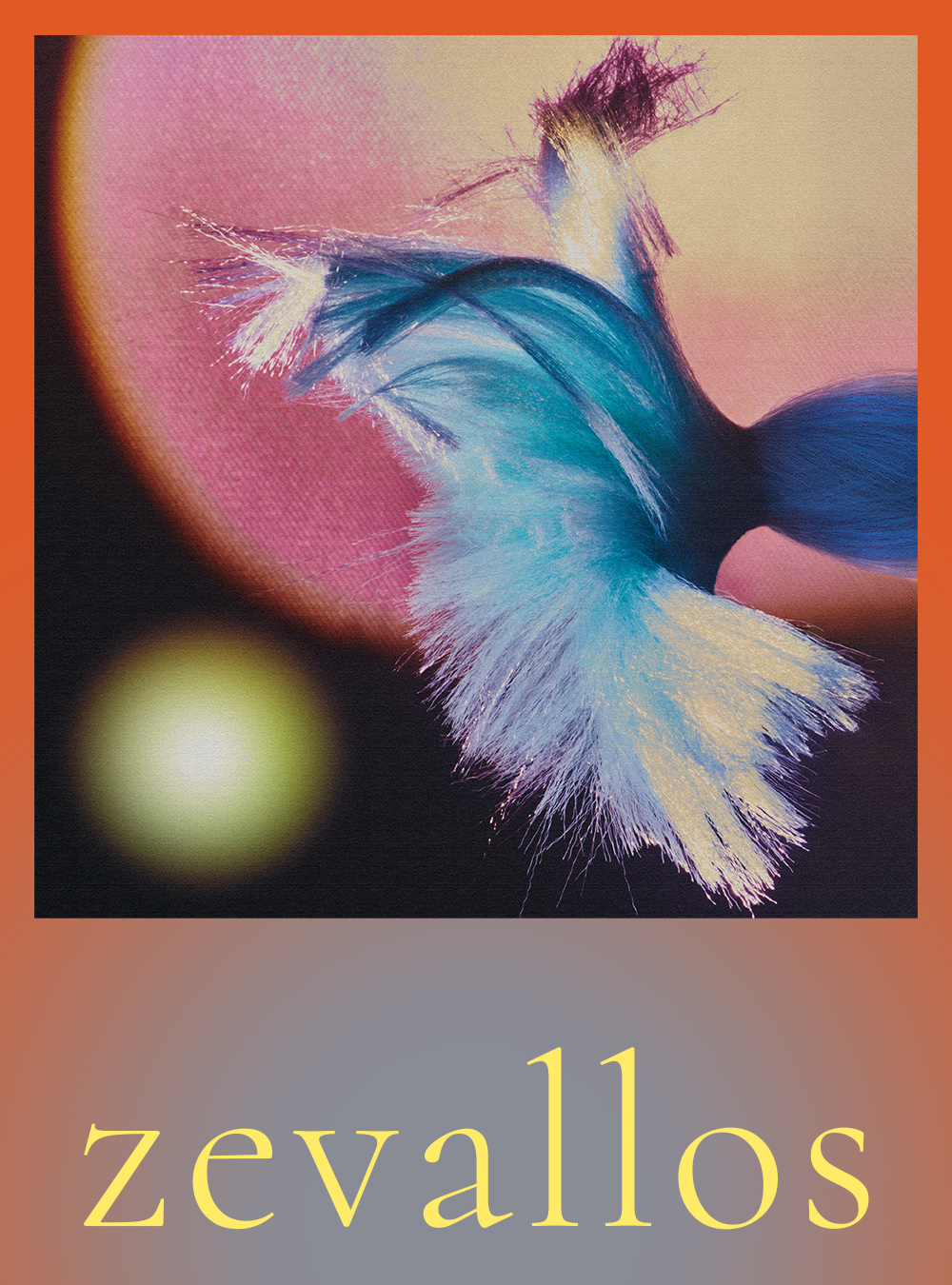

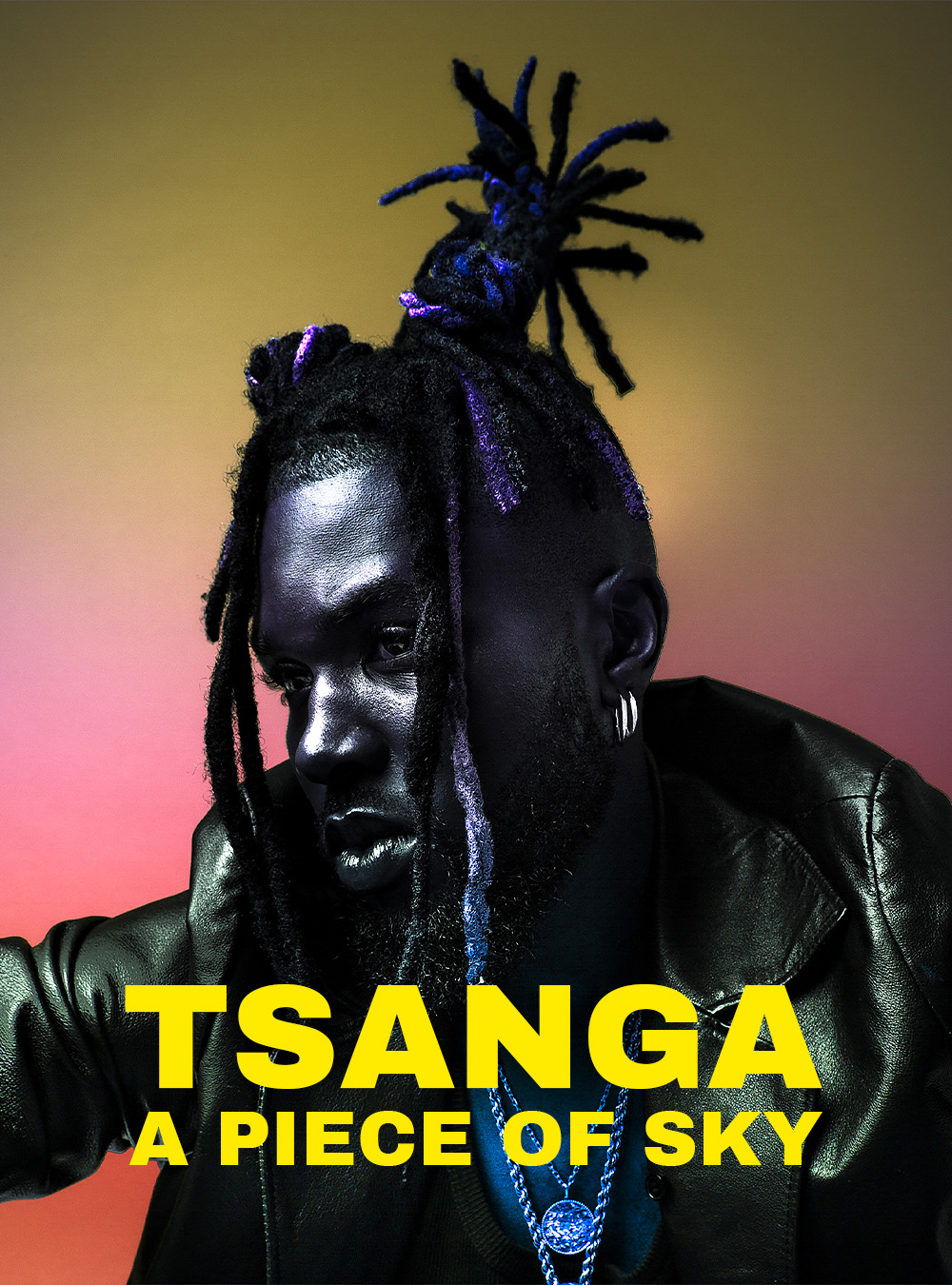

Céline Bodin is a French photographer whose works have been exhibited in London, Paris, Amsterdam, Munich and Krakow. After graduating from a photography bachelor’s at Gobelins, L’êcole de l’image in Paris, she went on to do a photography master’s degree at the London College of Communication. Bodin’s skills don’t end with taking thoughtfully beautiful photographs, she also writes about her photography and articulates convoluted phenomena of human perceptions in regards to history, nature, and cultural and social complexities.

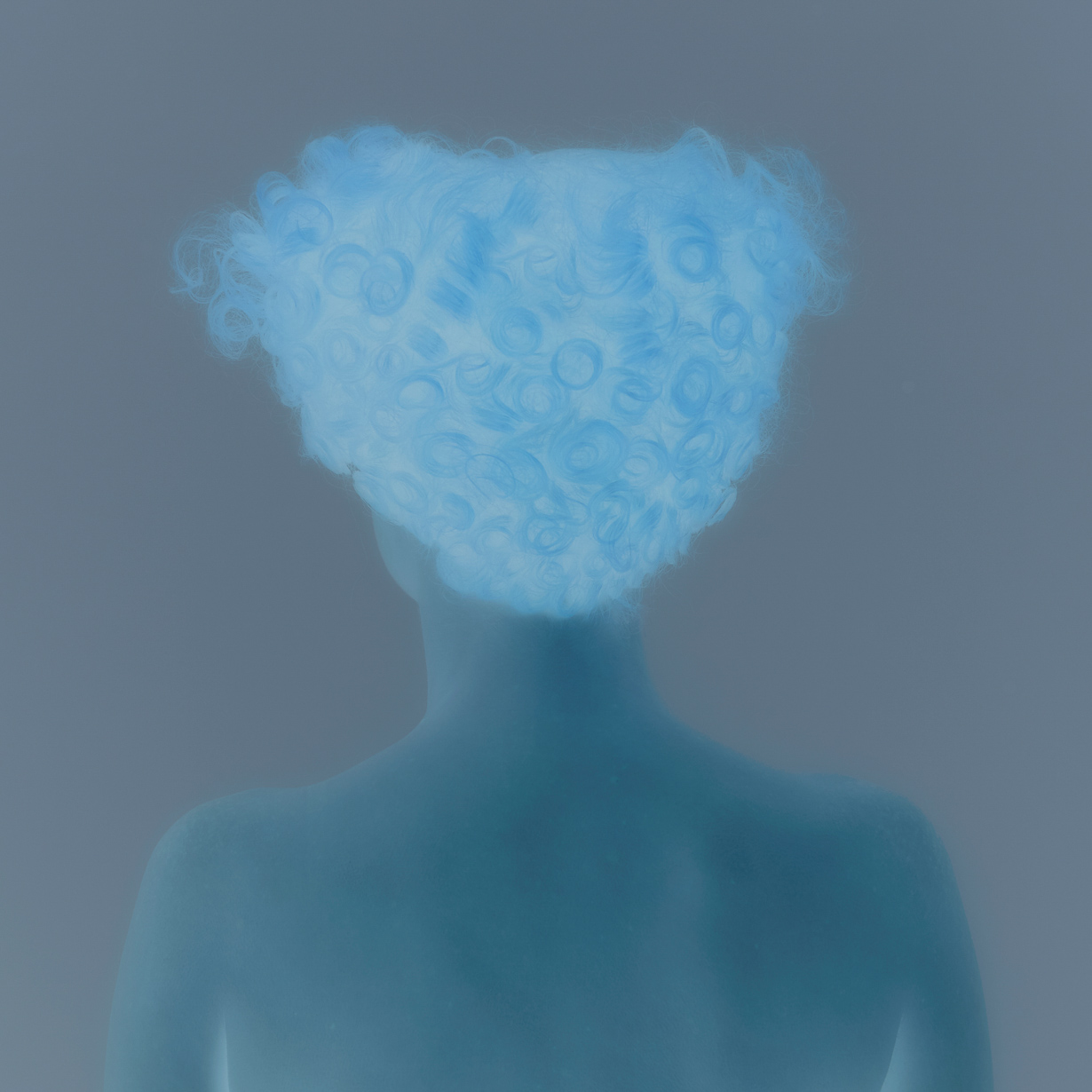

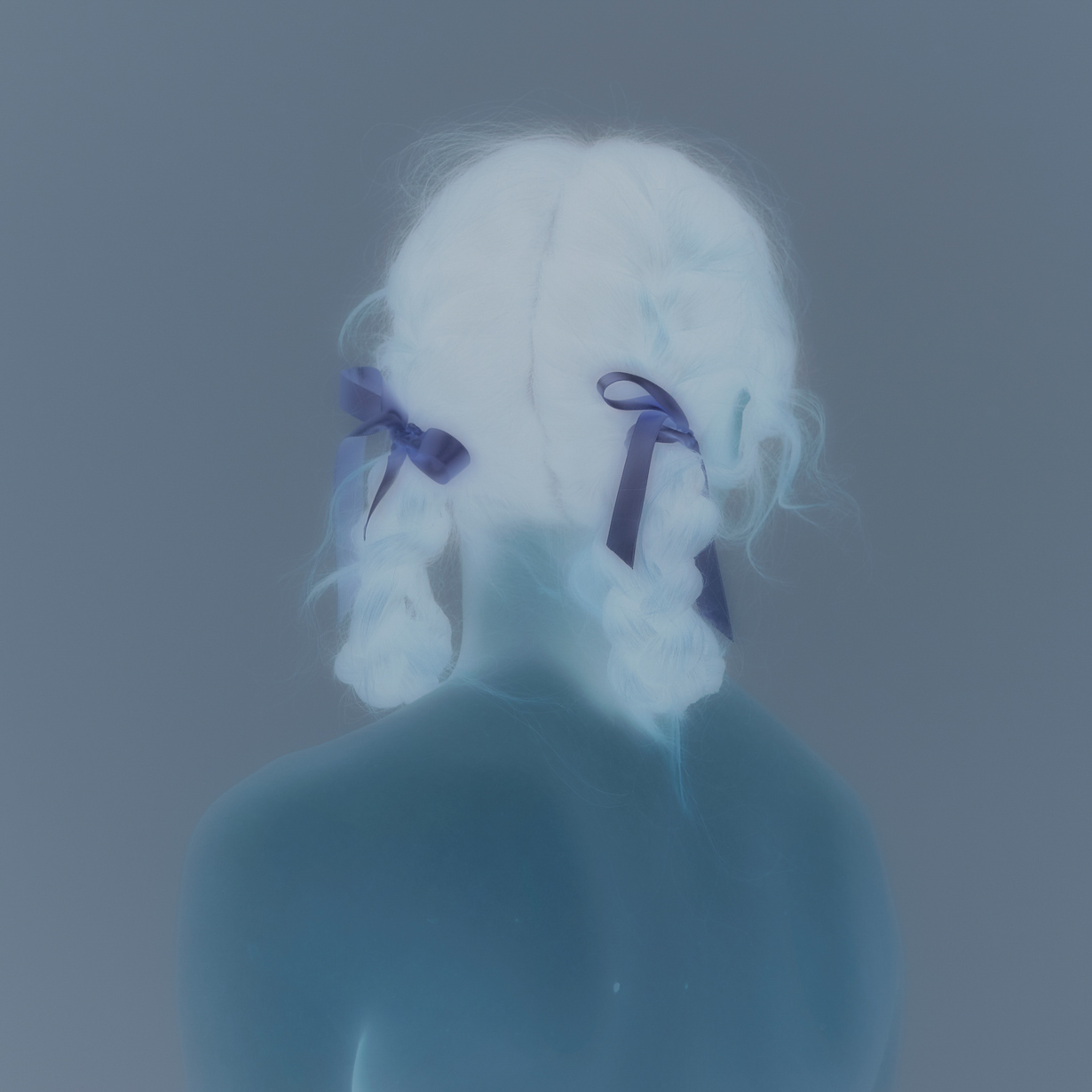

In her 2018 series The Hunt, Bodin creates a collection of portraits of Western women’s hairstyles throughout different historical periods. Topless models shot from the back create a clean canvas where class and facial beauty are eradicated and the viewer’s sole focal point becomes the hair. One photograph shows a woman with highlighted brown hair, styled in a Victorian braid that is so long and thick it wraps around the head again and again. Another photograph shows a woman with peroxide blonde lob where the ends flick outwards in typical 60’s style. This work asks the viewer to fill in the blanks – who is the woman depicted? What kind of woman is she? Is she beautiful? And while there are no correct answers, the blanks that our associative thinking fills are, in a way, all correct, as it was never about the answer itself but about how we think our way there.

How did you first decide to explore hair as a theme? I have a certain fascination for representations of the past. Before we framed portraits of loved ones there were Victorian hair medallions. This fascinating practice reflects on the hair’s pictorial quality as a material but also its link to identity. As a pliable, removable, and growing element, hair is the human medium of transformation. It lies on the margins of the physical self.

The more I thought of hair the more I thought of all the hairstyles I’d seen and known that defined the myths of “female types” our mind instantly associates them with. It felt important to present as many of them together as possible, to re-affirm the influence such beauty dictates in the definition of womanhood.

What are some recurring themes across your works that you like to explore? My projects all interrogate the representations of women across time and explore the construction of womanhood, in response to the pressure of customs, social expectations, beauty dictates, religious righteousness, the legacy of art history, as well as the mystification of the fragmented body as an erotic entity and a sacred incarnation. My images point out our tendency to consider identities as types, and our mind’s powerful associative aptitude. For The Hunt (2018), the different hairstyles reflect on the feminine types that women have been reduced to, a cabinet of curiosities onto which fantasies are projected.

Overall, objectification and the body’s performative quality are central subjects to my work, as well as notions of archetypes and fantasised projection (both from self and viewer). Recurring themes are: the weight of visual traditions, hair, the symbolism of wedding dresses, the white colour as a symbol of purity. And more specifically the duality of female attributes: sensuality vs spirituality for example.

“As a pliable, removable, and growing element, hair is the human medium of transformation. It lies on the margins of the physical self.”

What role has gender played in your exploration of hair and its stigmas and associations? Although nowadays our relationship to hair is much less contrived, looking at old paintings, vernacular photographs, and films, hair is actually a very strong pointer to gender. In my photography I only work around the principles of female representation, and in particular the construction of the feminine cult and the definition of Beauty. My general research is largely based on the writings of Simone de Beauvoir, John Berger, and Julia Kristeva.

In many religions, hair is considered sacred. It is either that it cannot ever be cut, or shall never be seen, as it is a pointer to female temptation and ultimately references sin. I always found this a fascinating idea. Why hair? Perhaps because it borders the wild, and connotes natural instincts.

Women have, throughout history and still to this day, been reduced to their physical attributes and their aesthetic choices in their appearance. Looking at the extent of creativity in hairstyle, it is easy to suddenly feel as if we are observing the evolution of a mythological creature. I think the lack of freedom that was inherent to women in the past has directly infused them with a wish to create their own story: a story that was first taught through their appearance. Somehow a woman is dual: herself and her character, whether it is in accordance or against social expectations – let’s think of Elizabeth I vs Marilyn Monroe.

You talk about a fantasy in the viewer’s imagination being created, of the subject as a person and their life, based alone on an anonymous hairstyle. How similar do you think different viewers’ fantasies and projections are when they look at the same photograph? To me what is interesting with this series is its anonymity yet affirmed stylisation. Here the fragmented bodies’ inertia asserts the preconceived idea of the perfect female form: Eve has taught the world of women’s faults; her flesh has left women in a quest for ideals. There are many ways in which women have answered this quest but hair has, since early times in history, been central to the expression of their appearance.

When I speak of fantasies I refer to the projections of a character associating to the type of woman she wants to see in herself, as well as a viewer projecting their ideas of femininity onto a woman portrayed from the back, defined only by her hair. I think this is something we do every day: we do not so much project on her personality and her life, but much more on the type of woman we think she is, whether we picture her as sensual or conservative. The images in this series are like the formulas to an iconic concoction: glamour icon, quiet beauty, innocent youth, garçonne, skinhead, free spirit or nymph, Elizabethan Queen… they all acknowledge the power of hair as a strong representational element, and are gathered in a build up to reveal all the notions that have created our idea of femininity through time.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR