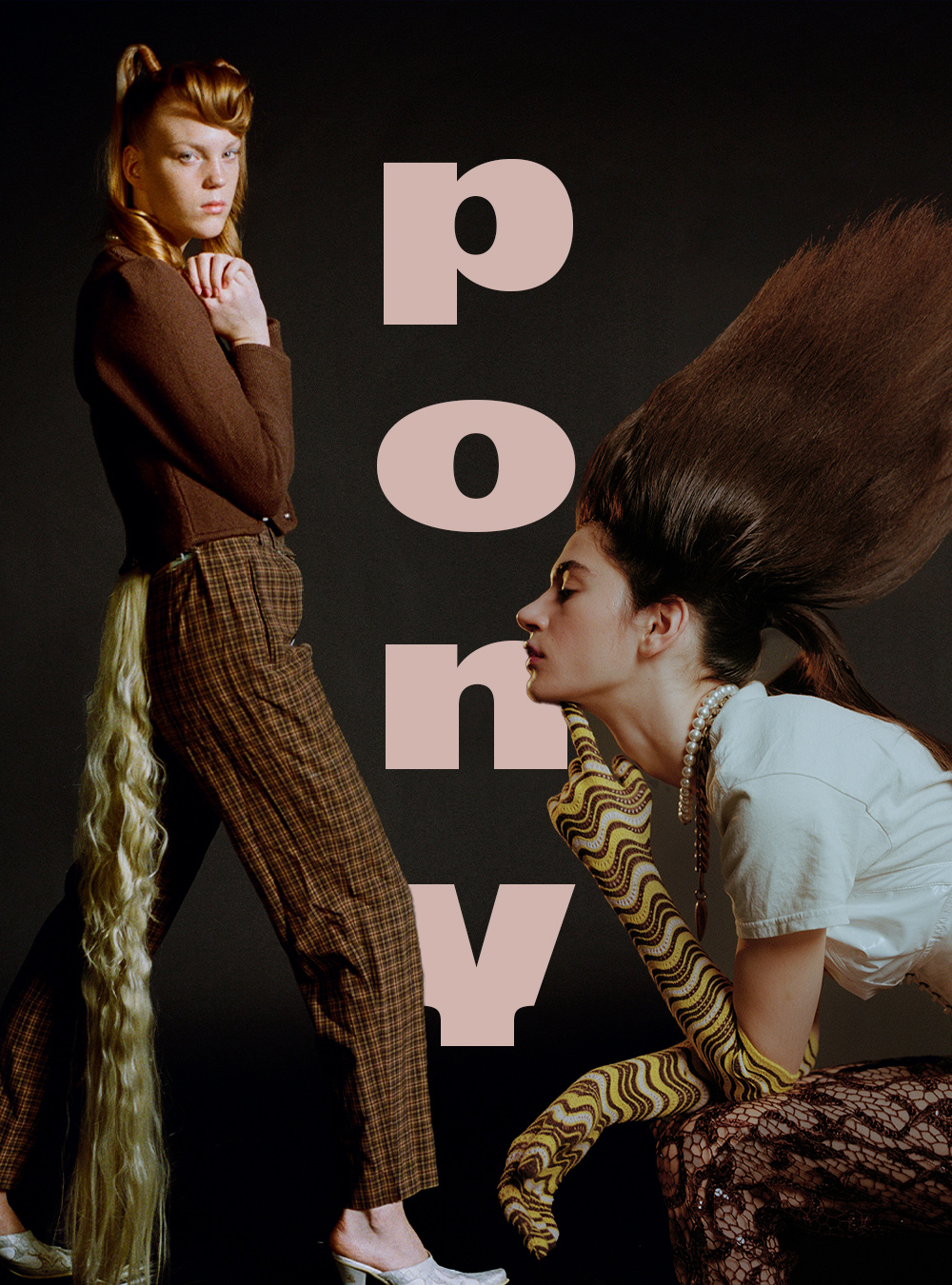

ART + CULTURE: Artist Amy Pennington speaks on the significance of queer and trans affirmation through hair and art, and the process behind their lookbook collaboration with Open Barbers

Interview: Katharina Lina

Art: Amy Pennington

Photography: Amy Pennington, Panos Damaskinidis

Salon: Open Barbers

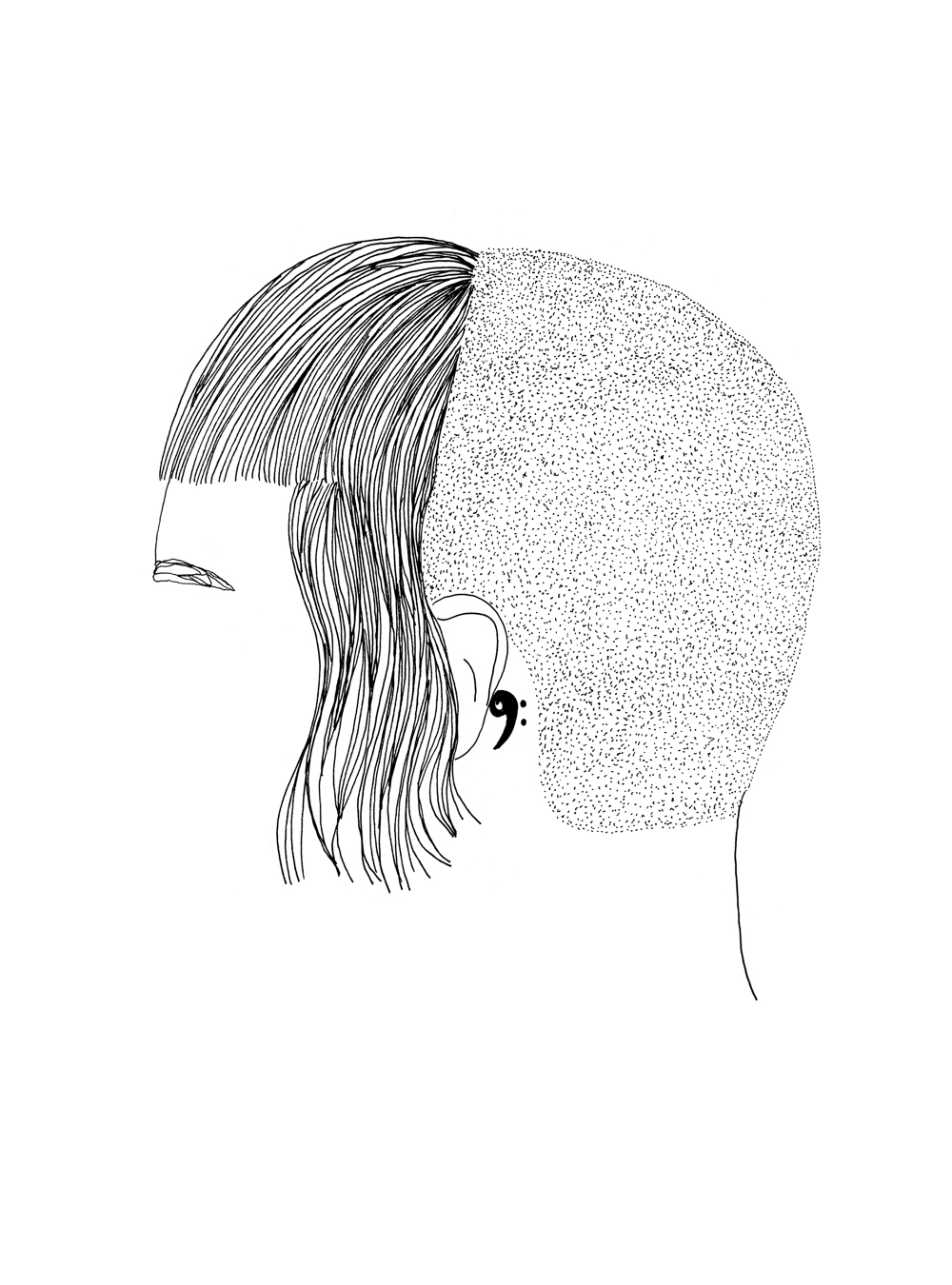

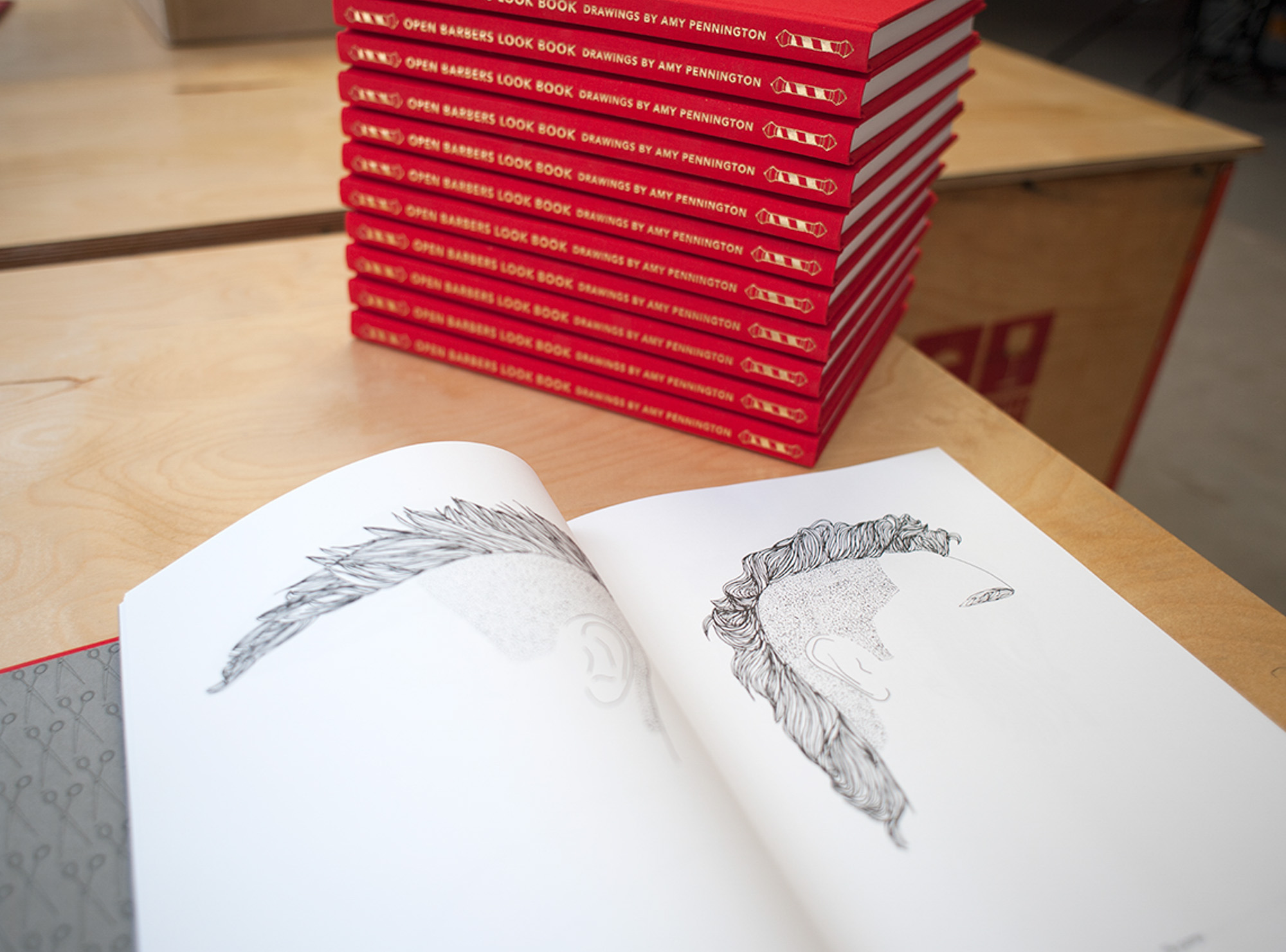

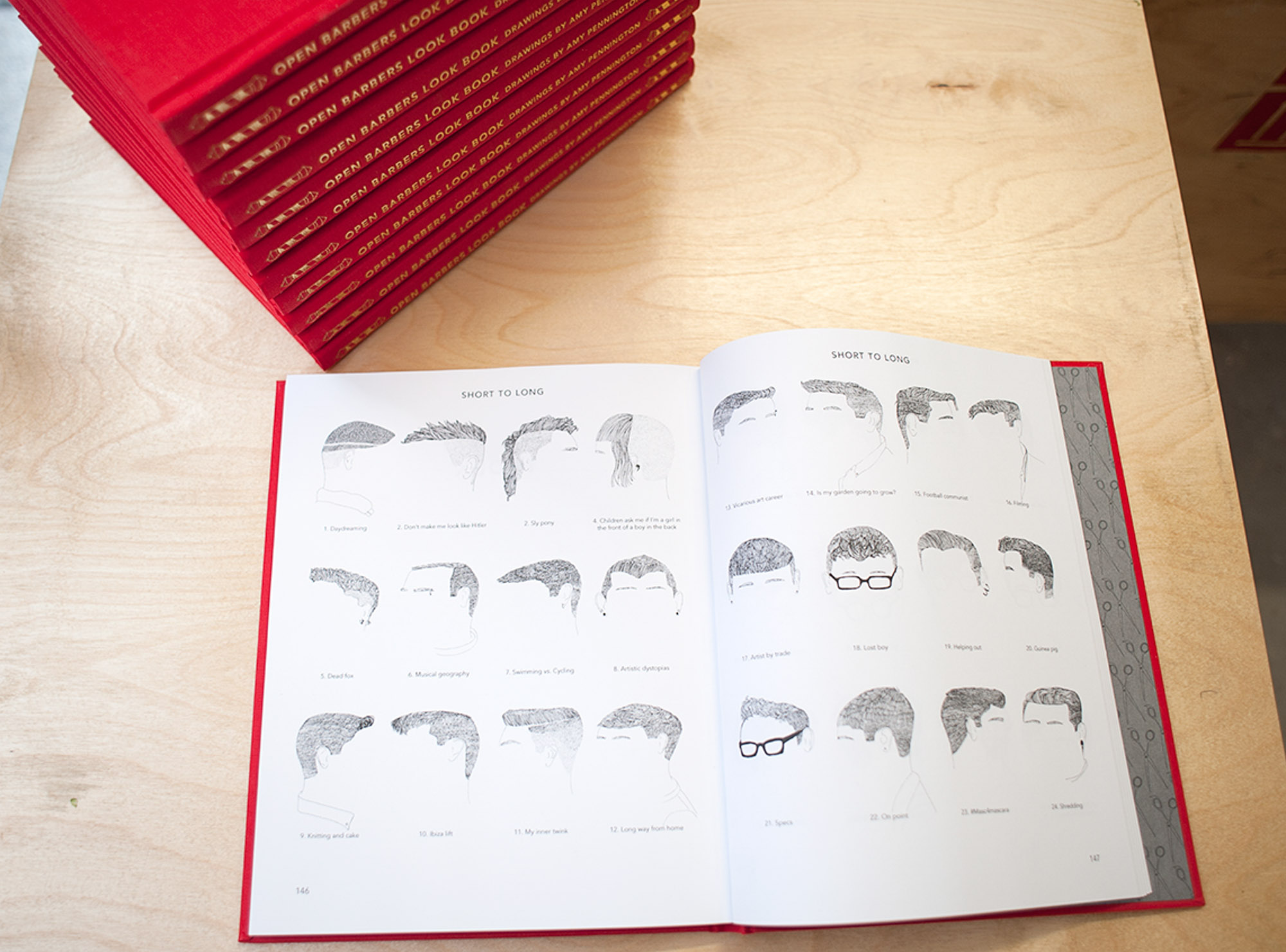

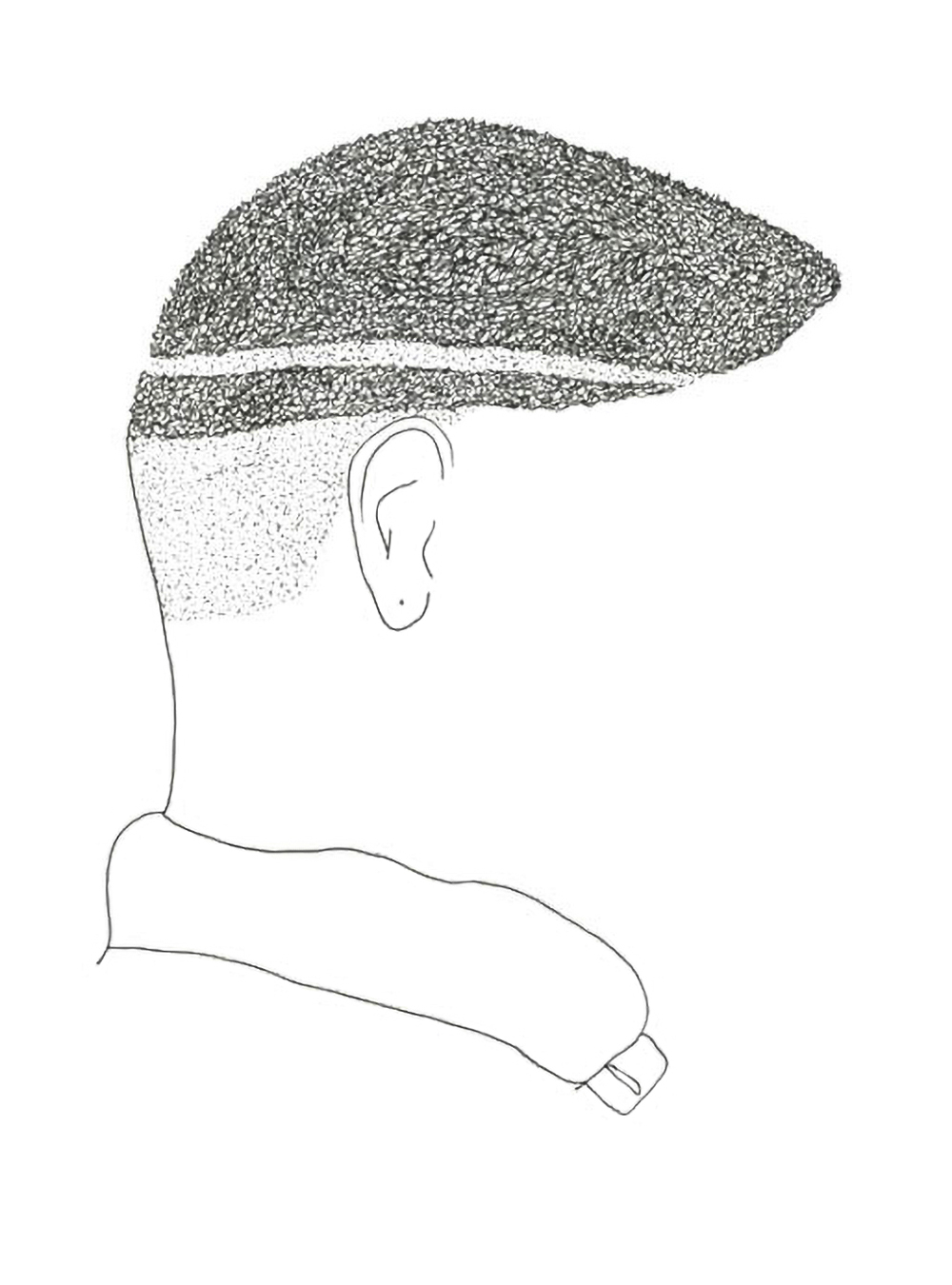

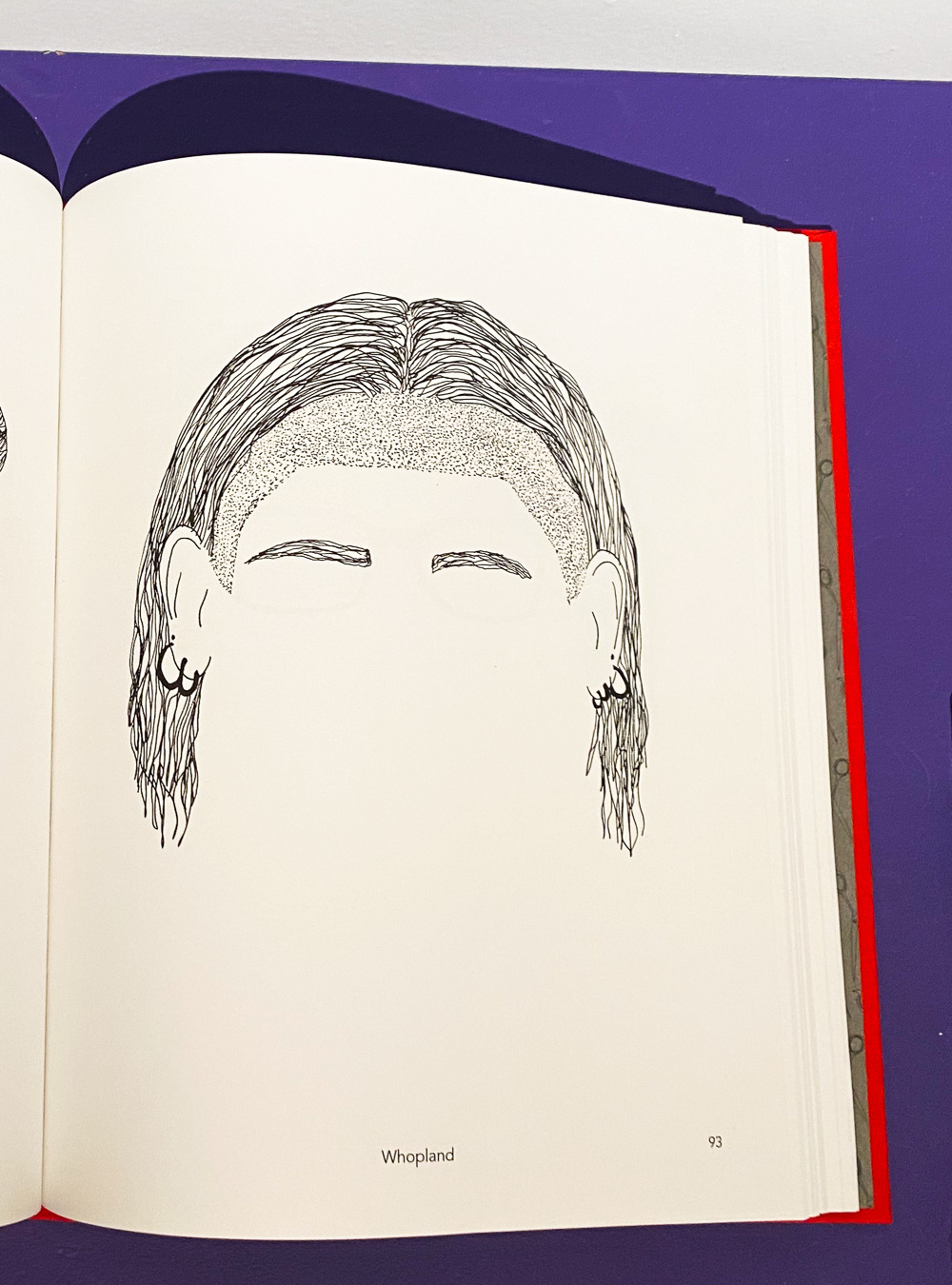

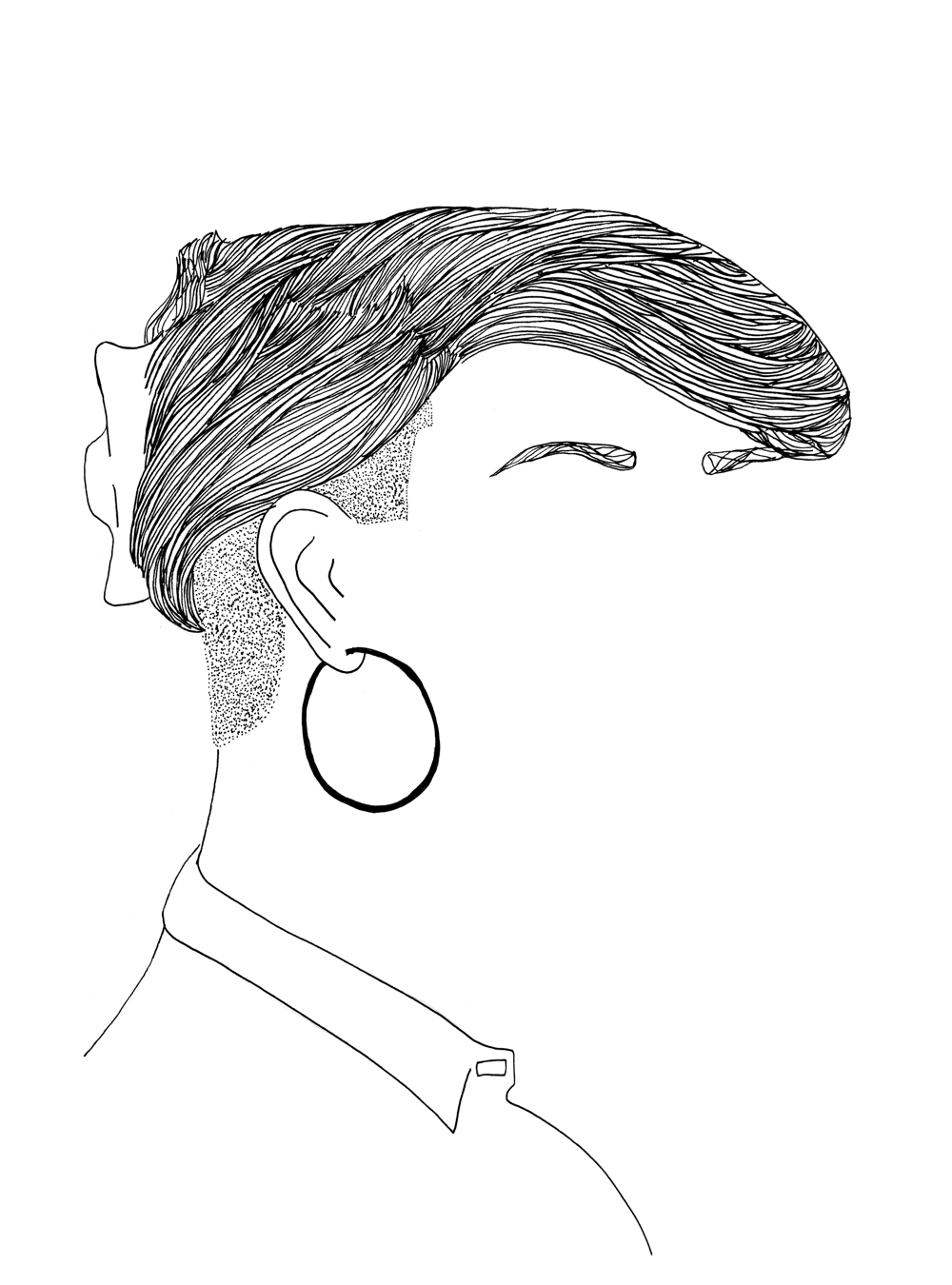

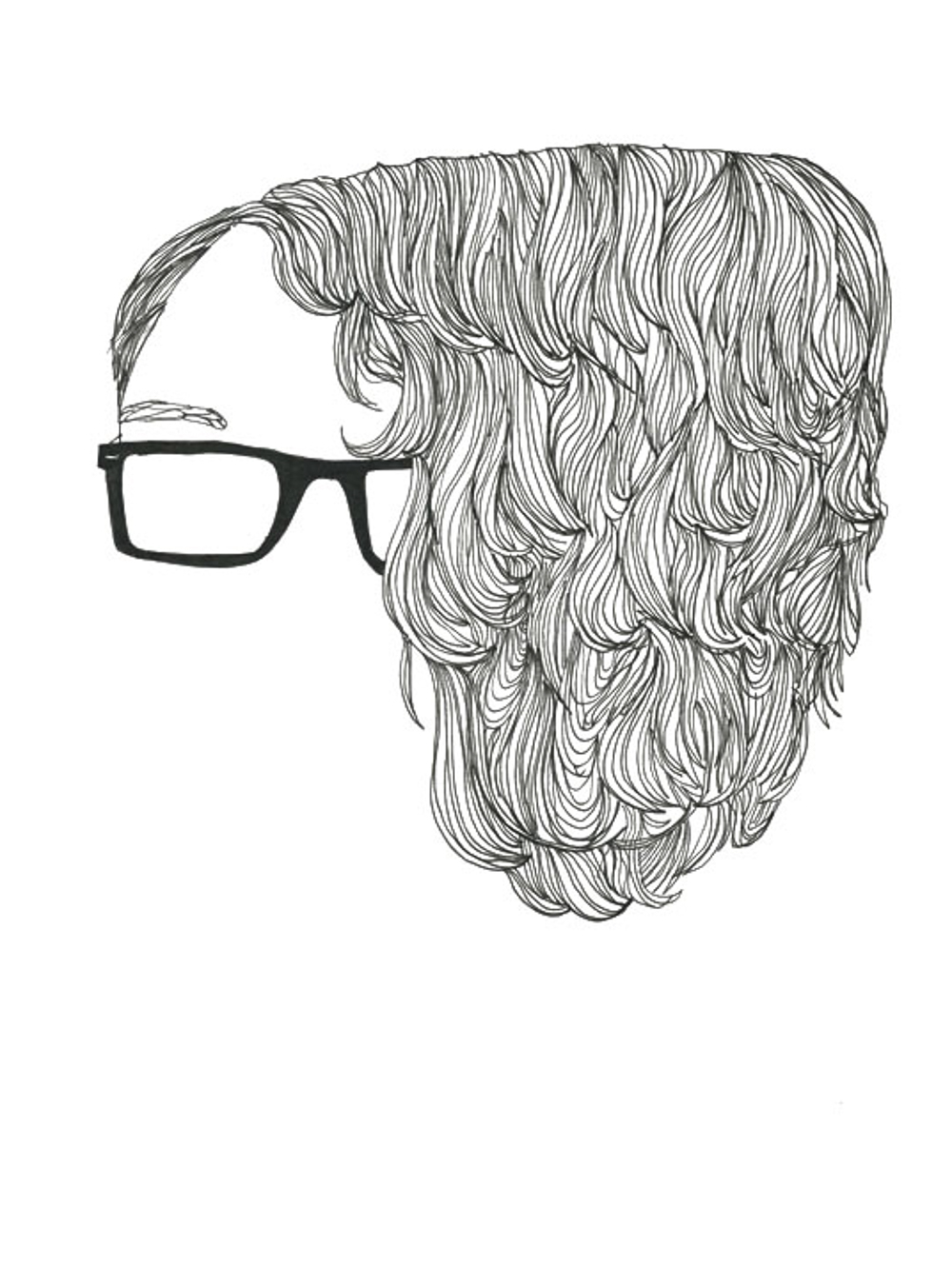

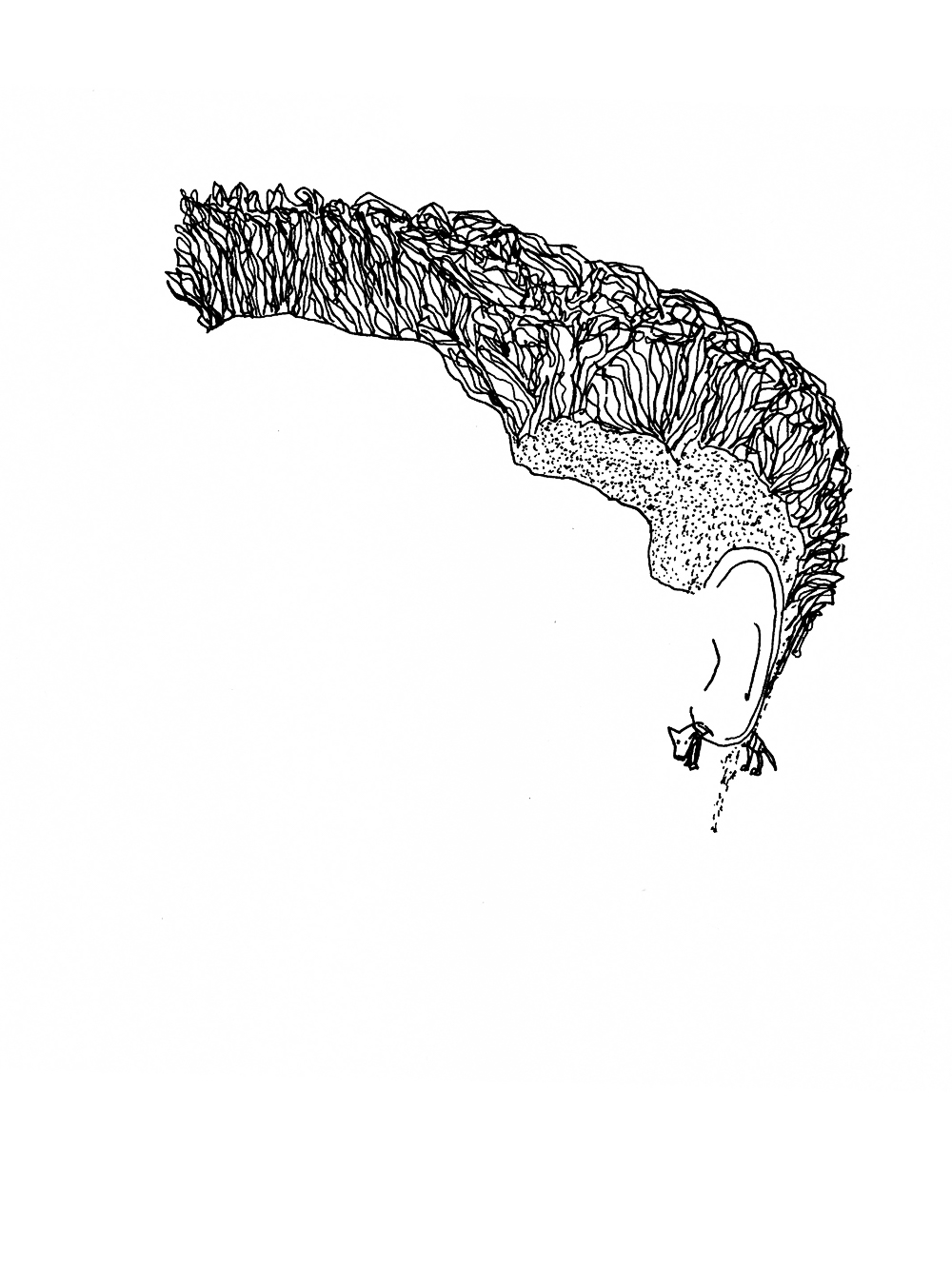

As more and more high street salons have standardised their services being priced according to hair length rather than gender, it seems almost comical that once upon a time it was assumed completely normal that haircuts were charged depending on whether it was a woman’s or a man’s head from which it grew. Way ahead in 2016, artist Amy Pennington teamed up with trans-led hairdressing service Open Barbers to create a lookbook of hairstyles that are just, well, hair. No faces to attach beauty standards, no bodies to project gender expectations onto. Pennington, who uses a variety of media and humour to connect human experiences and socio-political issues, likes to take an immersive and social approach within their work. For this particular project, Pennington wanted to explore a hair salon, a space they once frequented as a teenager. “I worked as a ‘Saturday girl’ back then, but now I’m non-binary so I guess ‘Saturday person’.” Bursting with warmth, creativity, and loyal customers seeking interesting hairstyles, queer-friendly Open Barbers provided a perfect environment for ideas to flourish, and over the course of 5 months, Pennington met and drew three to four people a day for a few days a week resulting in over 200 hair drawings that have been compiled into a book.

"Because there aren’t any facial features, it encourages you not to focus on what gender you think that haircut is for. It takes that away from you and hopefully that really amplifies the fact that gender is a construct"

How did you and Open Barbers first come together? I often like to go and do residencies in spaces where sometimes artists don’t get to go and do them. I’ve gone into a factory and done some work there, I’ve been to a working men’s club – I’ve been to all kinds of different places. I guess sometimes I do art in an untraditional way. I thought I’d really like to go to a hairdresser’s and do some work there, and I noticed that I had often gone back to some of the jobs I had before I became an artist. I used to be a care worker and I had gone back there as an artist and spent a year there. And then I guess I’d gone back to a hairdresser’s where I used to work as a teenager. There’s something interesting in that.

I was looking at local hair salons near me and then I went to Duckie one night and Open Barbers were doing a pop-up shop there and I remembered them and I thought I’d really love to go there actually. I really wanted to meet with them because I loved what they’re about. I thought what a great thing for the queer community to have. I got in touch with them and eventually we got together and did a trial. We did the trial for about three weeks and then we realised that it could materialise into something more.

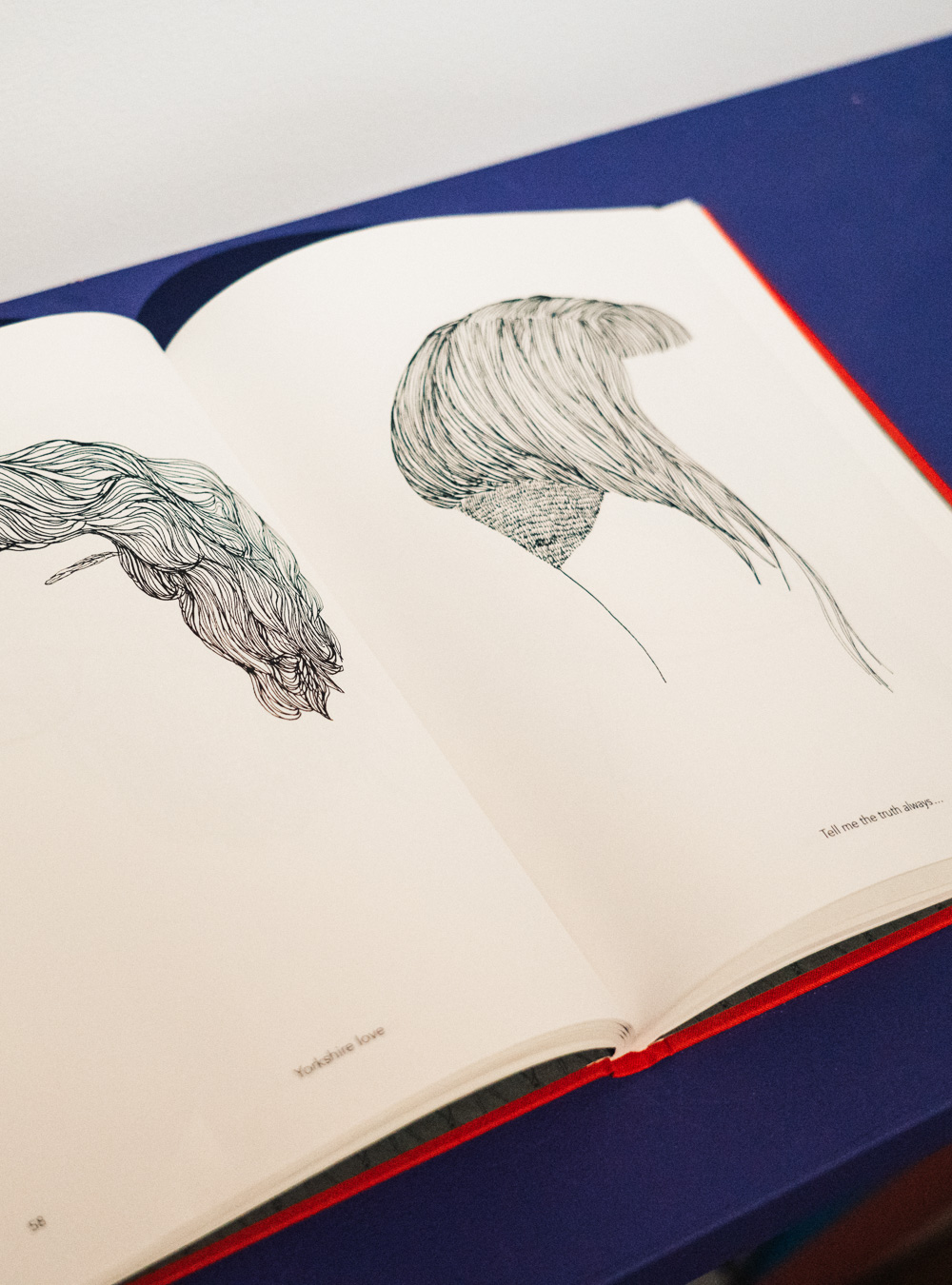

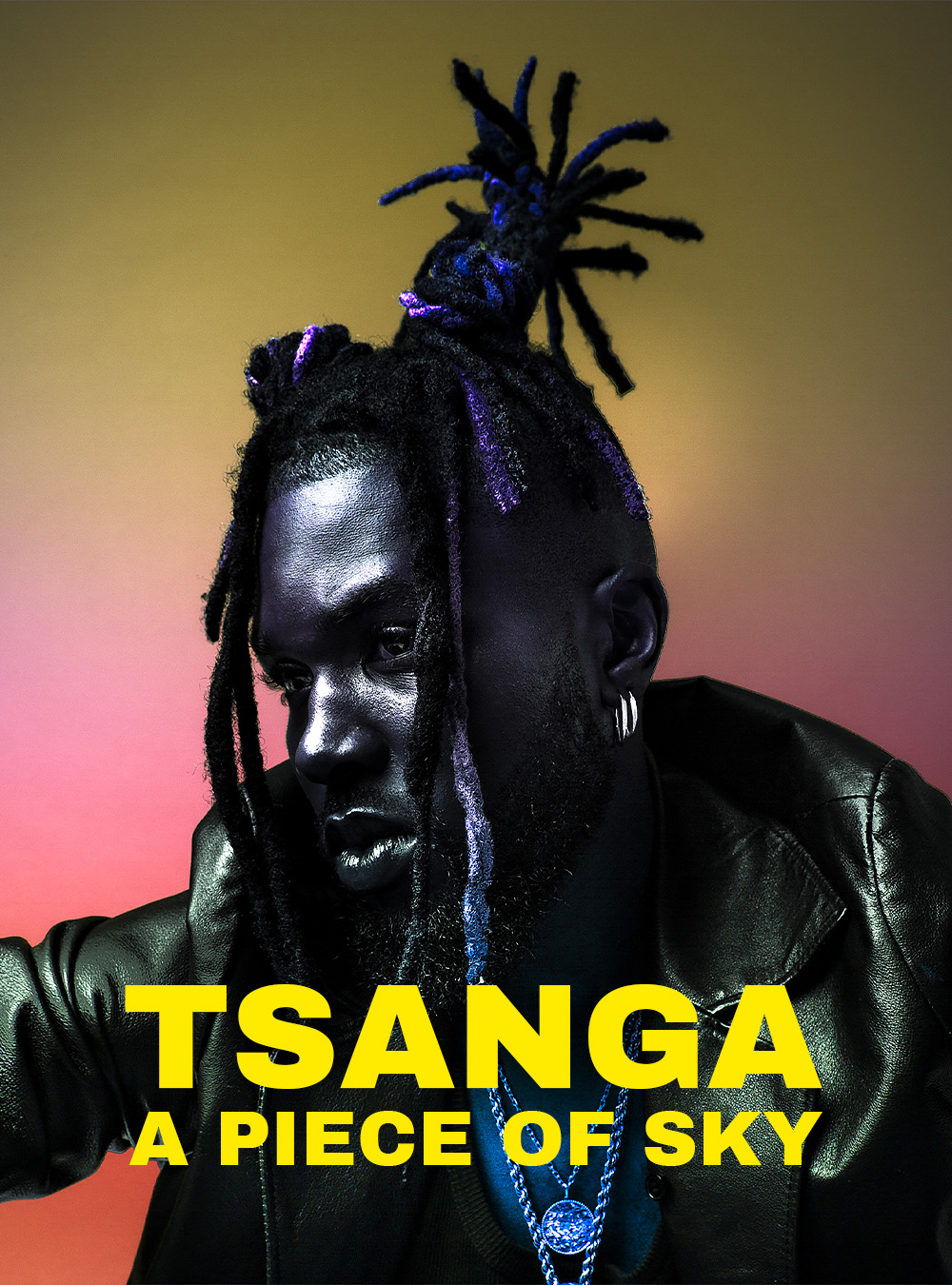

How would you say did the immersive practice shape the work? I guess it was a one-on-one experience being drawn like that. What I thought was quite nice about that was that you’re being totally seen as a queer person, as a trans person. You’re being really looked at and seen and this is going into something that is hopefully going to help other people. They sat down and some people wouldn’t talk and some people would. Some people were talking about how hungover they were or what they watched on Netflix, someone might have been talking about a book that they’d been reading, or it might have even been something very personal like how their transition was going. There was a whole range of things that were spoken about. This also informed the work because I asked people to name their drawings and often people would say ‘Oh I don’t know what to name it’ and I would suggest we’d look at some of the things that we had been talking about. That’s where the titles in the book come from, they’re all the different bits of conversations. I’m flicking through the book now and there’s one here called ‘Lint Roller.’ Another one here called ‘ACAB – all coppers are bastards(+councillors)’ Here’s one called ‘Blunt’, one called ‘Yorkshire Love’, or ‘Between a lazy bestie and a cute flat mate’ and ‘Queer magical realism.’ We spoke about so many different things and naming the drawings was a way for the conversations to be noted, without being recorded in any way. It was really important to me that the actual conversations stayed between me and that person.

Did you find there were any limitations to drawing inside a bustling salon? I think some people just didn’t have time even though they wanted to stop and be drawn. But I totally get that, we’re all busy people. Some people I even photographed and I would draw them afterwards because they still wanted to be part of the project. There were ways for us to get around limitations, but it was mainly time more than anything. I really loved all the bustling salon bits happening around me. When there was down time for me I’d just sit and draw the clippers, or Barbicide, or Greygory’s legs – I loved drawing the little bits in between of it all, all the ephemera.

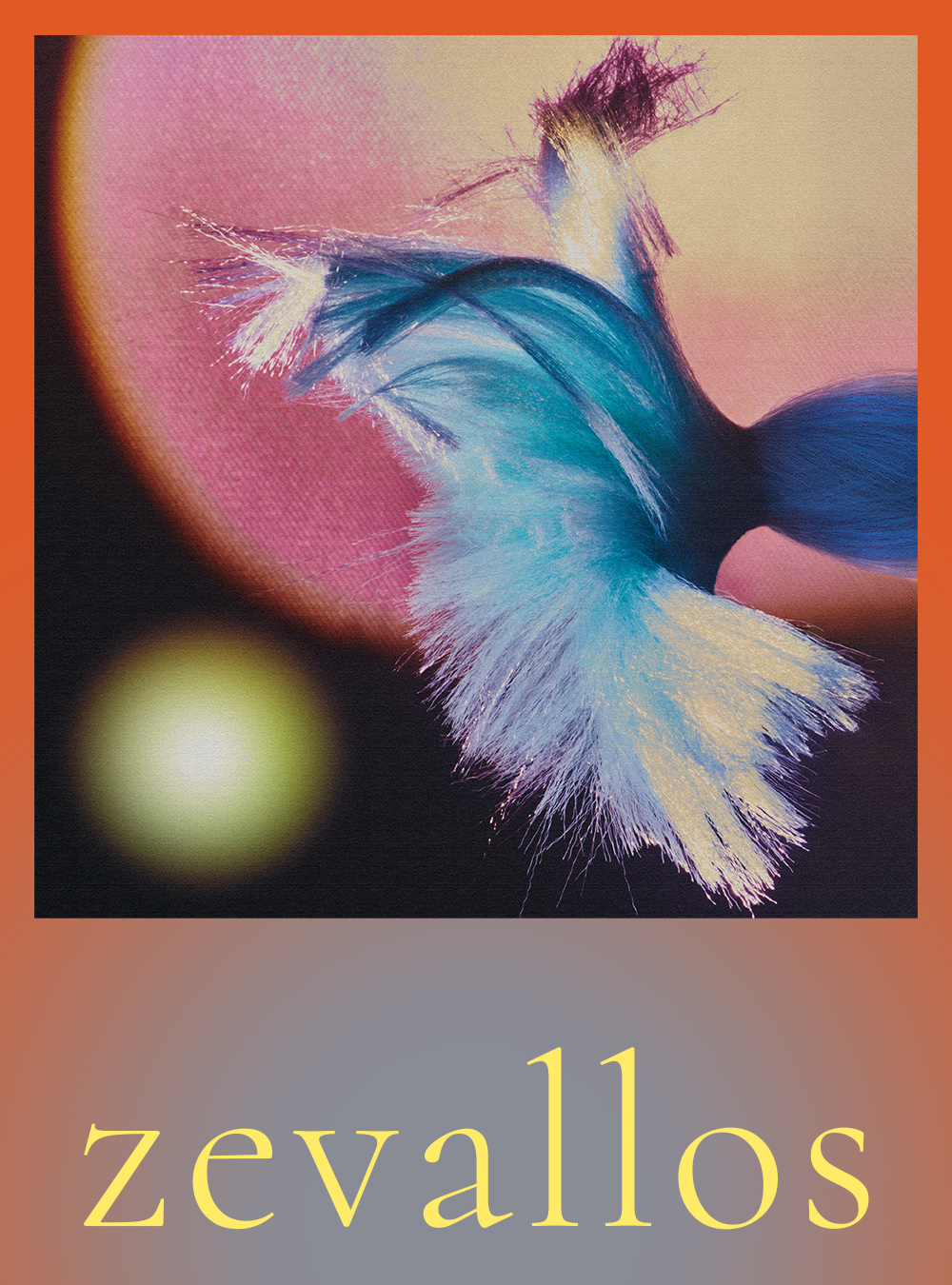

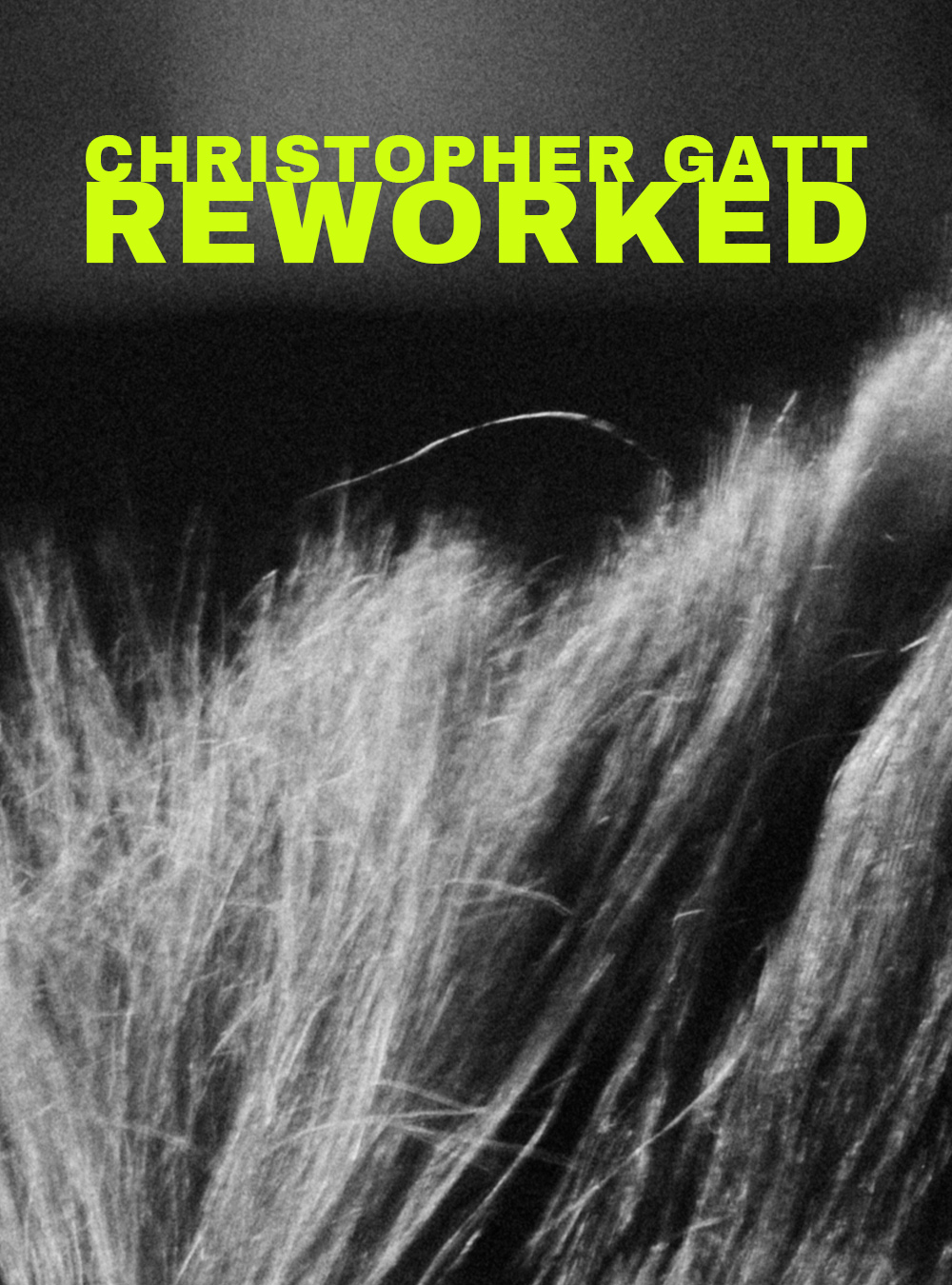

Greygory and Felix previously mentioned the constraints of narrow beauty standards and gender expectations still prevalent in the beauty and grooming industry. Can you elaborate on the significance of removing personal characteristics from your drawings and the positive impact this could have on an individual? Traditionally, hair and beauty standards have a real binary of male and female. I think for the queer and trans community especially this traditional way of looking at it is problematic and confronts a lot of issues. To reinvent that and show it in another way is really important and that’s why drawing queer people’s hair was a way of celebrating that. If you’re just looking at a haircut that hopefully you’re really happy with because you’ve just had it done and it really affirms your identity and you’ve had a great experience while having it done, I think this can be a real gift to some people. We have to question why, traditionally, we’ve gone down such a binary route. Hair is just hair. The way the lookbook is structured, you go from short to long, all the haircuts are sorted by length. Then we’ve got undercuts, patterns, fringes, sideburns, and back hairlines. I think that’s a great way of looking at hair; hair that is genderless. Because there aren’t any facial features, it encourages you not to focus on what gender you think that haircut is for. It takes that away from you and hopefully that really amplifies the fact that gender is a construct.

Would you say your previous experience working in a salon had somewhat shaped your understanding of these beauty spaces? When I first met Open Barbers and trialled the work I came to understand what a special space it was, because I grew up and worked in this very traditional small town hair salon where hair was very gendered and the binary was very much enforced. Going to such a caring and loving space that Open Barbers is… I think what’s really important is that they truly listen to what somebody wants. Hair is often such a big part of your identity – especially when you’re queer, your hair becomes so much about your queerness as well, it’s all interlinked. It’s important that a hairdresser is working with you and what you want, not push their beauty standard or their beliefs of how genders should present. It’s about what you want and I think Open Barbers are really good at listening. I saw such a difference to where I worked as a teenager that I realised just what a special place Open Barbers is for the community.

Copies of the book can be purchased via DM Amy Pennington for £40 inc p&p.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR