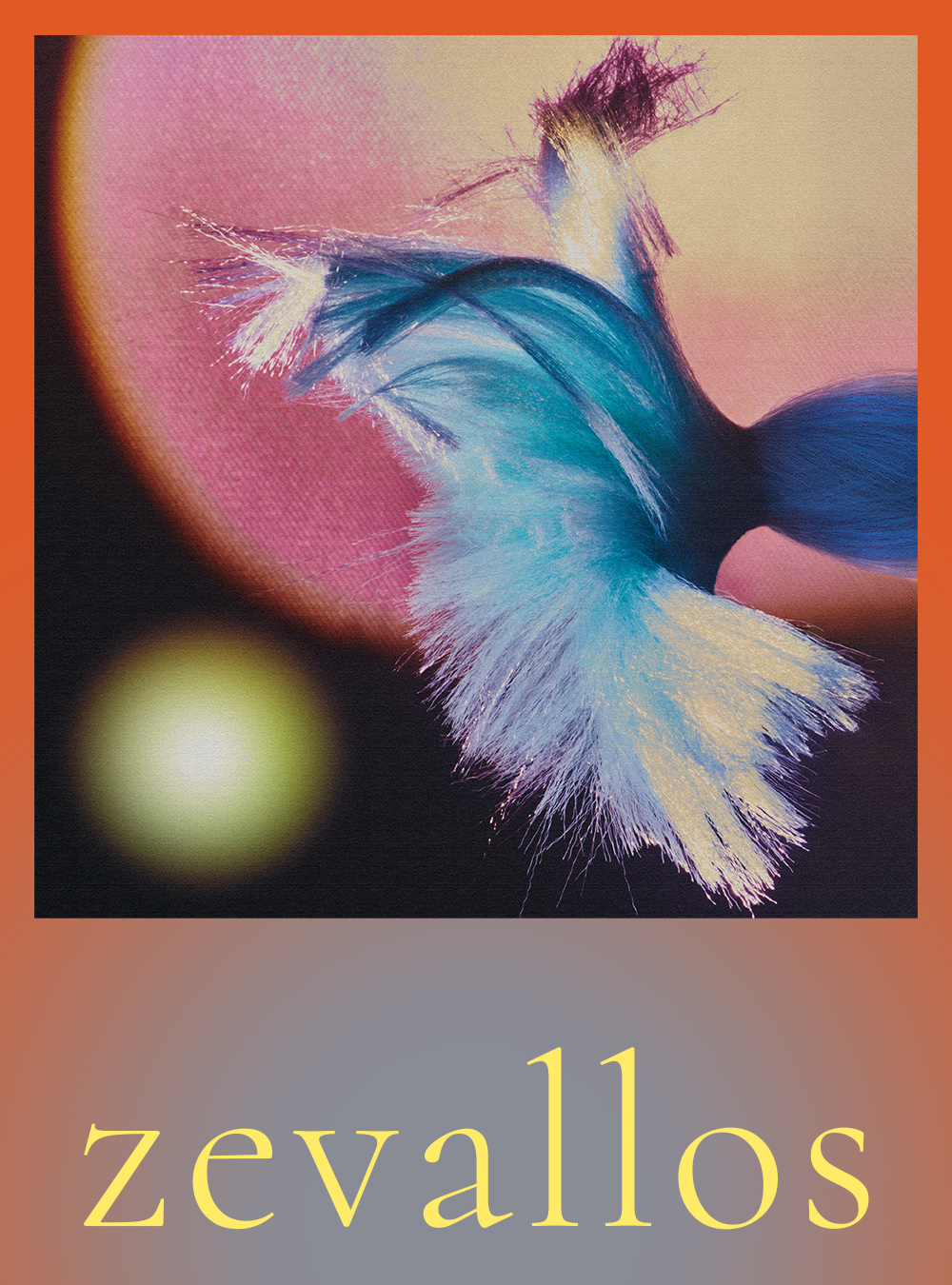

ART + CULTURE: Exploring the value we attach to hair as a product and a medium, Ana Mrovlje’s terse synthetic-hair sculptures awaken tensile narratives within the viewer

Featuring: Ana Mrovlje

Photography: Urska Pecnik

Interview: Hasadri Freeman

Exhibition Venue: Kresija Gallery, Ljubljana

Ana Mrovjle’s intermedia works form a gentle practice of reflection, both of the self and of our wider culture. In varied mediums, the Slovenian artist delves into the unconscious, placing emphasis on the process of each work’s creation. Past foci have included the act of observation (The Constant State of Emergency,’ 2016), chaos, collectivism and memory as they relate to industrialization and war (Peacestool, 2016), and the experience of rain (As Above So Below + Rain Diaries, 2019). Her recent exhibit, Part Time Human (2021), reflects on the body and its parts as capital and material that can be dispossessed from its humanity.

“As Baudrillard puts it, the body can be understood as a cultural fact and not a natural, biological one.” Exploring the fact and fiction of hair as both a product and a medium, a naturally occurring body part and a synthetic accessory, Mrovlje awakens an uneasy space within the viewer as she posits a multiplicity of meanings attached to the fibres that sprout from our heads.

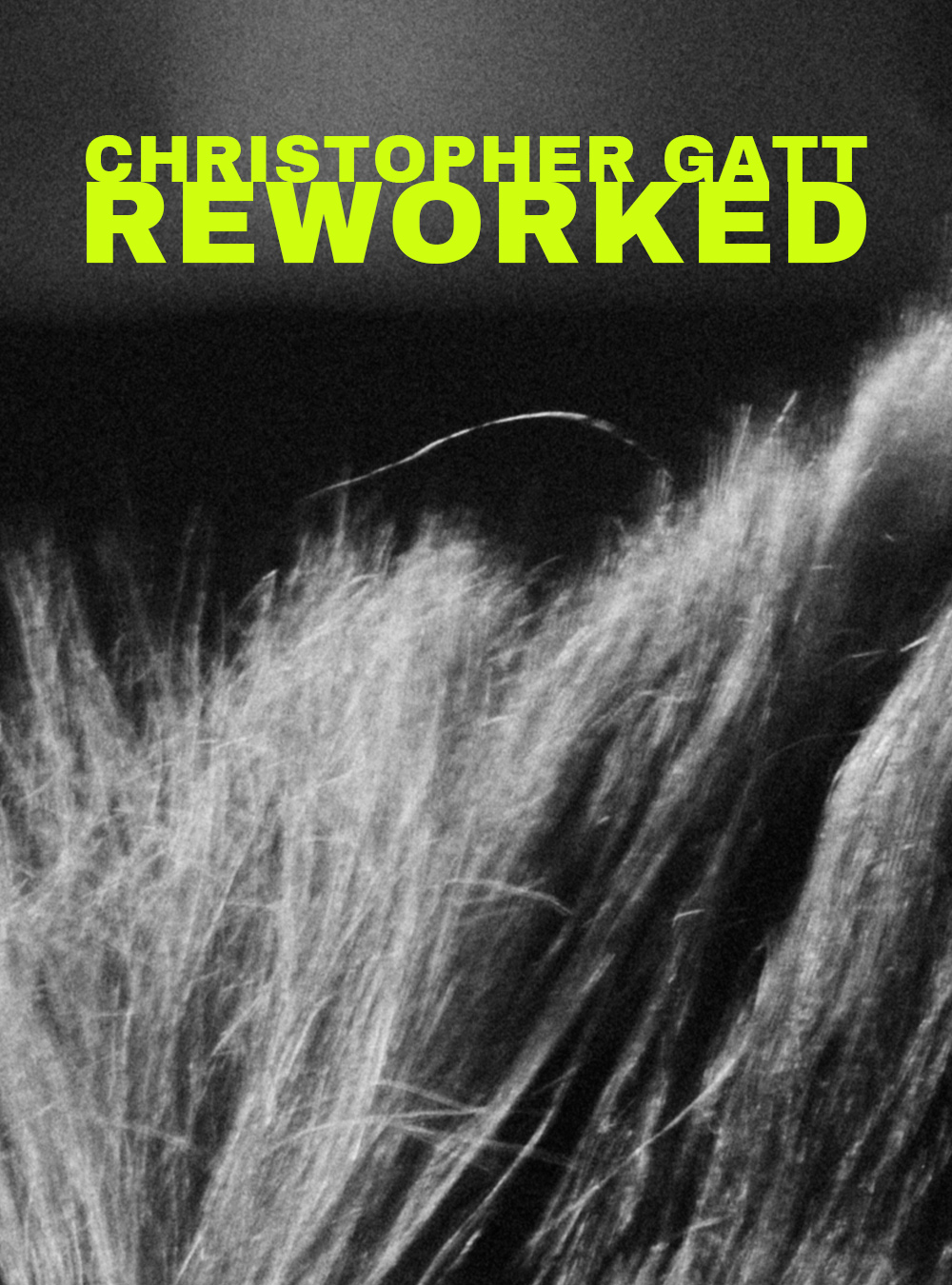

What was your method to bringing hair into your work for ‘Part-Time Human’? I chose an uncommon medium to produce this series of works through pure experimentation. Synthetic hair intrigued me, especially because when considered alone, it performs roles opposite to those it usually does within the textile or beauty industry. Taken as an independent material, synthetic hair is suddenly not meant to accentuate features or heighten existing hairstyles. When they are reformed in objects, they become self-providing entities with little initial meaning recognized in them, but I do think that the mundane is much more enigmatic than it looks. As Winogrand writes, there is nothing as mysterious as a fact clearly described.

The fundamental structure of Shapers (01,02,03) was made of aluminium and polyurethane. After fixing the objects’ initial form, I applied several layers of synthetic hair, creating the thickness of the texture.

The Boots TR131 are moulded in nylon mesh and then painted with an airbrush. I found the nylon mesh—which is mainly used in the production of hair buns—interesting, because of its transparent texture and elasticity.

What’s unique about hair as a medium, to you? What thoughts does hair elicit in a viewer? As a medium, it is very fragile. Its delicacy requires a specific treatment when used as a medium or in a more industrial sense. What started as performative objects which, when attached to my limbs extended the body in the studio, later evolved into individual, independent forms: objects that completely substituted for the body. The importance of a bodily subject to carry them gradually disappeared.

I work with the appropriation of organic materials, and my process culminated in working not with human hair at all, but it’s synthetic double—which unlike the former, has no biological trace or bodily value. As Baudrillard writes in his explanation of the hyperreal and simulacra, the works resemble the real, without the origin of reality. I explored approximating the human hair with something both its imitation and its biological opposite. Synthetic hair is chemically resistant and doesn’t submit to the external influences and passage of time like our bodies do. The objects exhibited—Shaper 01, 02, 03 and Boots TR131, TR132—are made entirely from synthetic fibres. Their materiality has nothing to do with the body anymore, even though the form and medium suggest it.

How do people react to hair in the fine art gallery space? How does the exhibition space recontextualize hair? When creating the works, I was intrigued by my own reaction to the emerging forms. At times I was disturbed—the black piece seemed so untamed that I was unsure I would exhibit it. The most common response from others in the final exhibition space was a perception of the objects as simultaneously fragile and aggressive.

The visual of the exhibition is singular and static. All objects are positioned on the floor, fragile and vulnerably exposed, on the same ground as the visitor. The works emerge from the floor and submerge back into them in different parts of the gallery, suggesting they may be interconnected under the surface. Positioned in a triangle, you can also see nearly transparent nylon objects moulded in the shapes of different shoes. Taking the form of prosthetics, they give an impression they have been left there or forgotten. All of the objects simulate human curves, materials and forms and give the impression that something has occured in the space of the exhibition; this fictional gap or potential event is left for the viewer to discover.

Who or what inspires you? What inspires me are new methods of producing art, those which change the perception of the self and the outer world. It’s important to realise that the centre of being is far outside of the human individual and that we are a rather insignificant part of the existing machinery. As humans, we have a lot to learn by accepting ecocentrism and reducing our human-focussed viewpoint.

What is your dream project? It would have to be something in the realm of working towards broader progressive outcomes. I want to develop new perceptions of living via a multidisciplinary approach: producing art with new tools, new technologies. I am interested in creating new forms, not yet defined, which the mind is not yet able to grasp but which an audience works to comprehend and thereby creates new visions for the future.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR