PEOPLE: Using hair, Parisian textile designer Antonin Mongin brings forgotten practices back to life

Works: Antonin Mongin

Photography: Caroline Faccioli, Antonin Mongin, Paul Reyrolle

Interview: Emma de Clercq

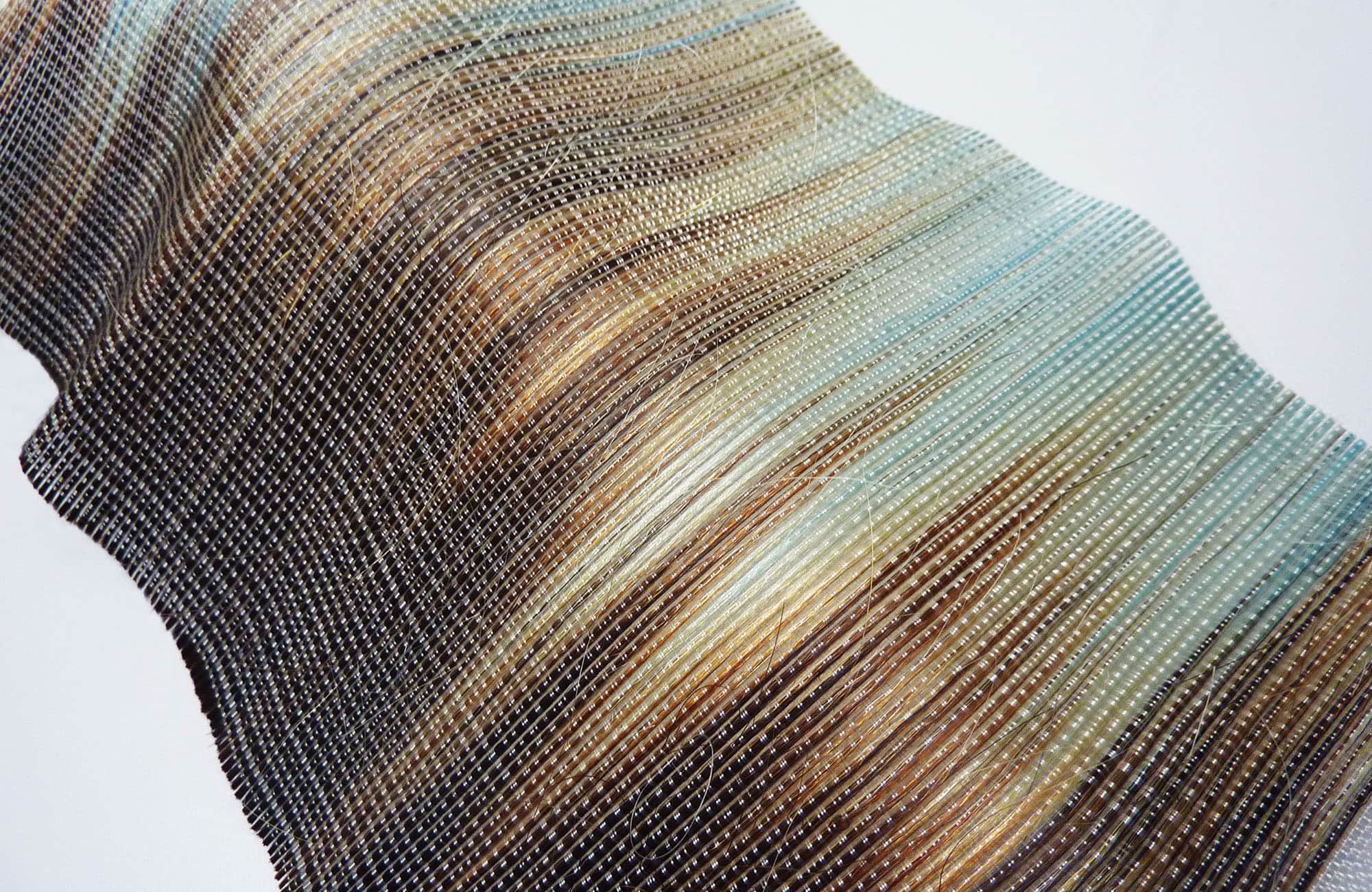

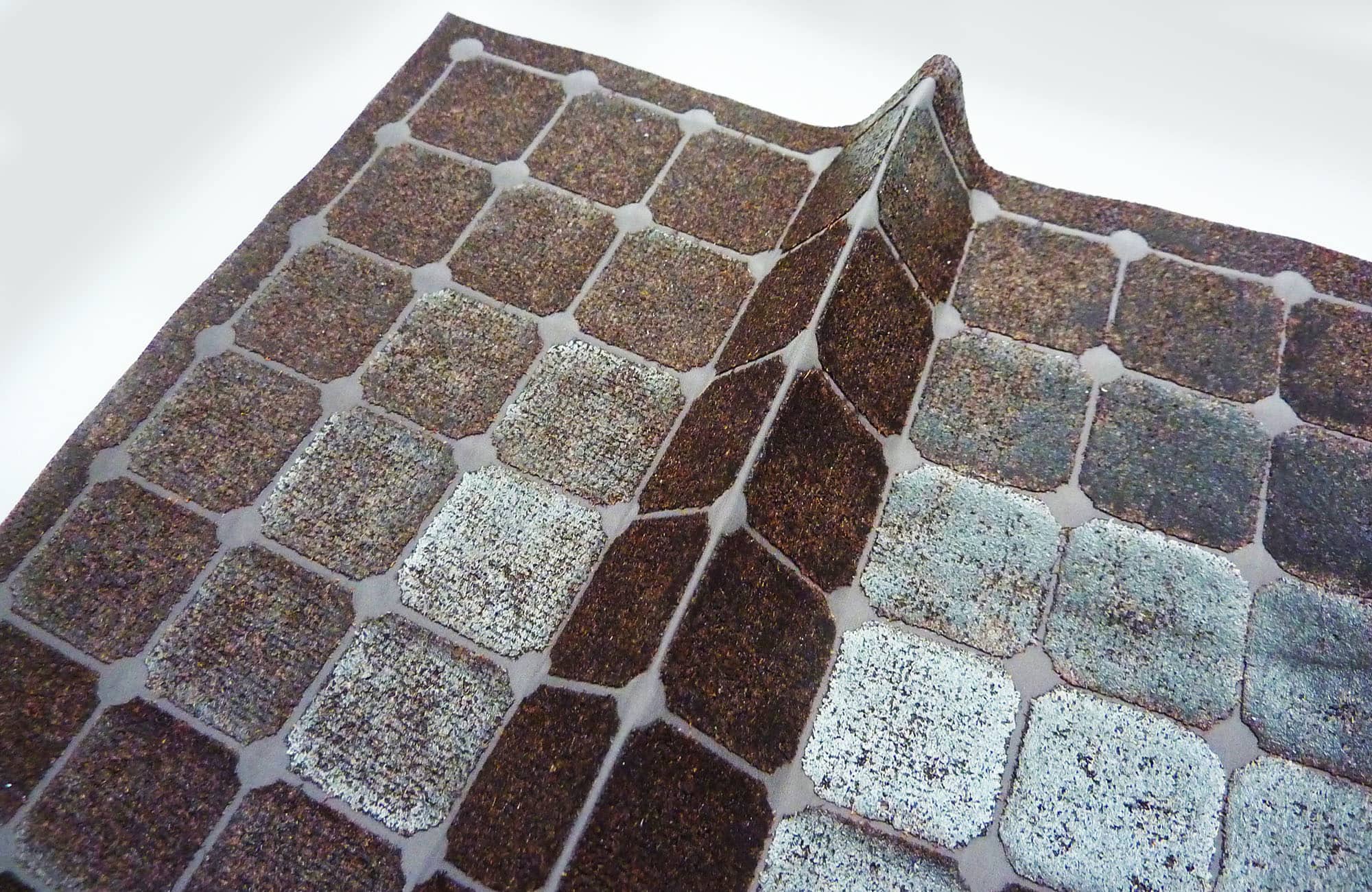

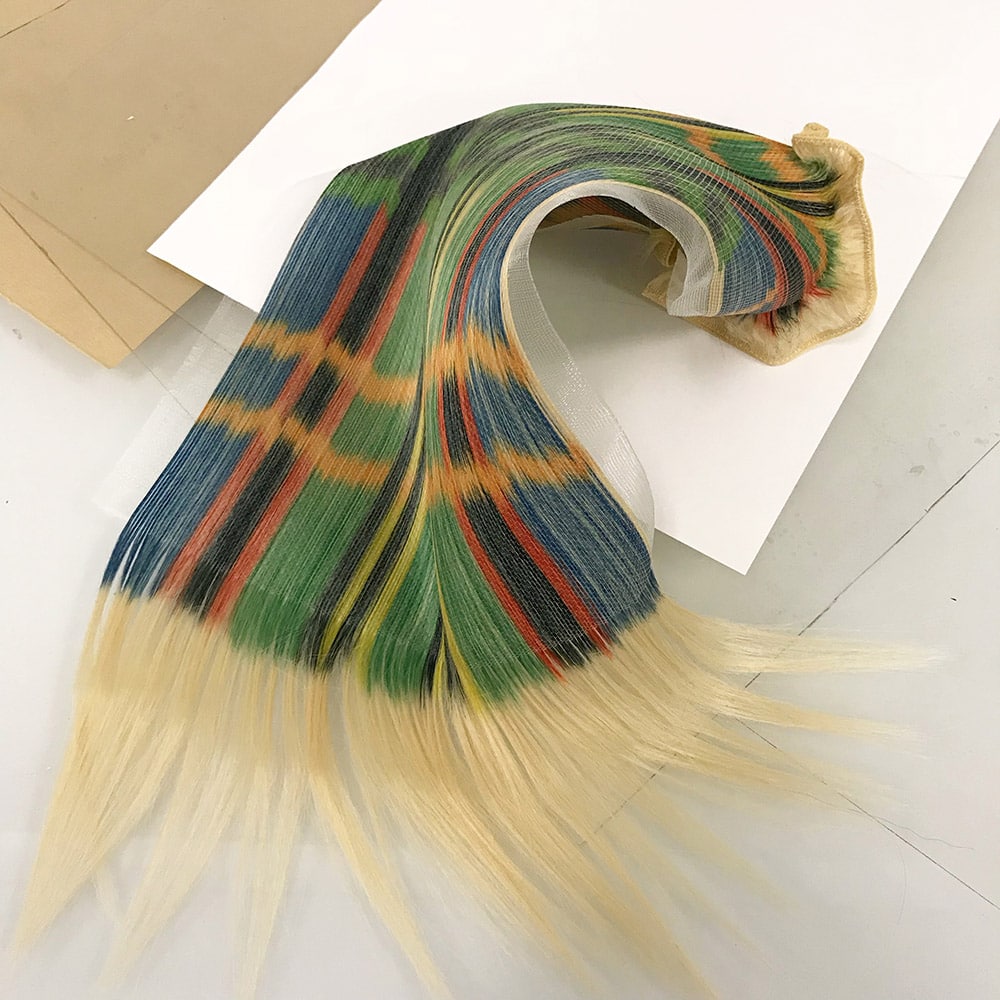

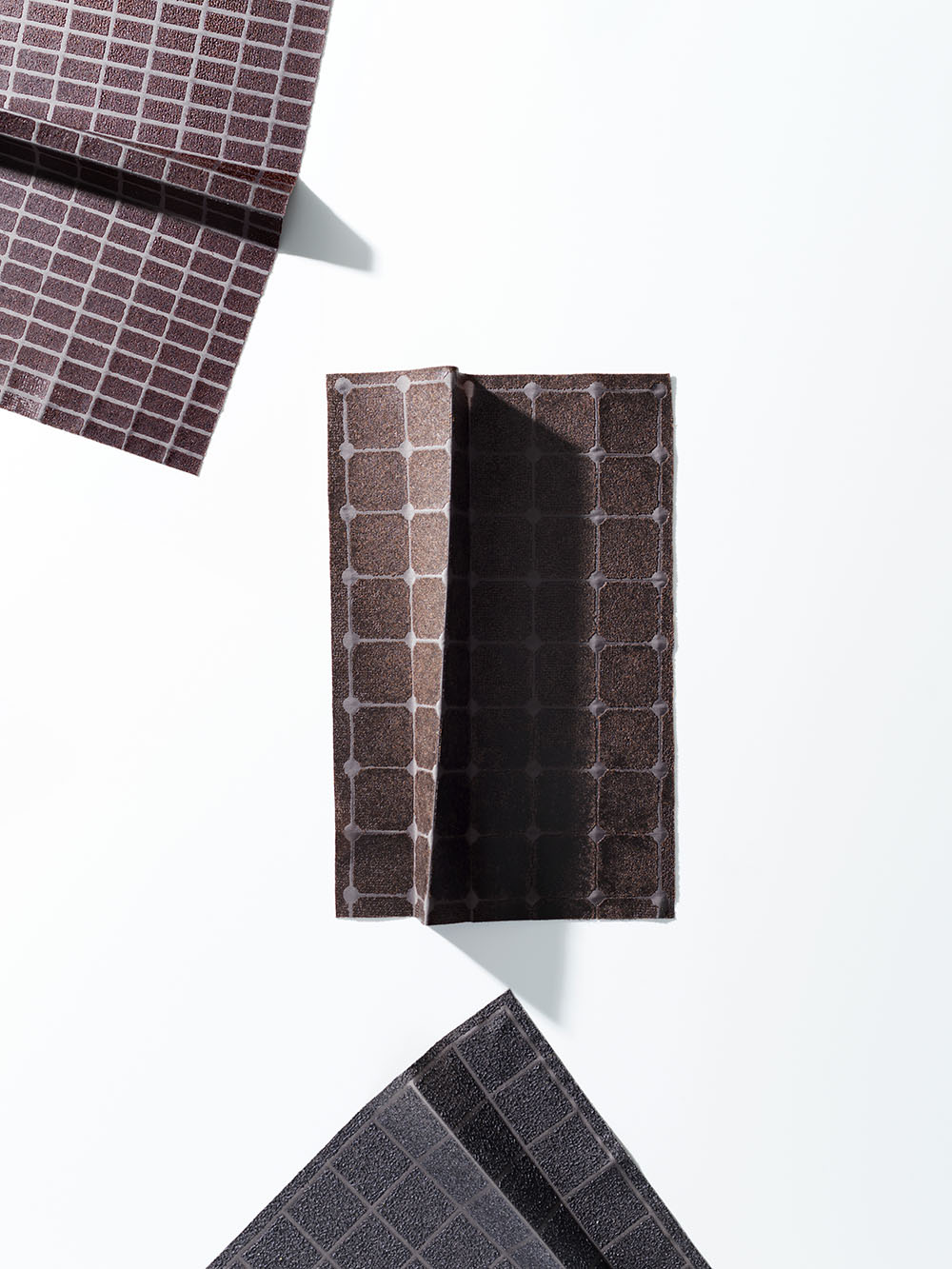

From sampling an Indonesian dyeing technique, to weaving on a French Jacquard handloom, Antonin Mongin explores different craft processes from all over the world. The designer has long been fascinated with the techniques used to create artisanal textiles, many of which have become dying art forms. Through his work, Mongin transports them back into the present day to create elegant contemporary objects, but with a twist – his pieces are all made using human hair.

While the fibre of hair would originally have been used in many of these techniques, in the form of wool or horsehair, Mongin’s use of human hair infuses his pieces with a distinctive personal element. It also nods to another form of historical craft that interests him – sentimental hair jewellery. This type of decorative practice, in which a lock of a loved one’s hair was transformed into a keepsake, reached its peak in popularity during the Victorian era in the form of mourning jewellery. Mongin explains that it is this element of intimacy attached to hair that fascinates him the most, as it allows him to “reposition the client at the centre of the design and production process of an object, through the prism of the material that comes from him or someone close to them.” After all, what could be more bespoke than an item crafted out of your own DNA?

How did you become interested in using hair within your textile work? When I started working with hair it was in response to these two questions: ‘what would be the textile fibre most intimately related to humans?’ and ‘how could I create a tailor-made and unique material for an identified individual?’ As a textile designer, we work with fibres of animal or vegetable origin, artificial and synthetic fibres. These raw materials are harvested around us or we manufacture them using chemical processes. However, hair, if we think of it as a ‘textile fibre’, comes from our own body. It’s this proximity to the source that informs my interest in cut hair. Moreover, when this human ‘material’ is used in a textile design project, it offers a range of very interesting qualities to work with: by its nature (rot-proof, presence of traces of the individual’s everyday life in its structure), its properties (elasticity, resistance, electrical, plasticity, hydrophilicity, hygrometric), its attributes (original, identity and aesthetic) and its symbolic values (profane/sacred and linked to an individual’s personal story).

What realm do you see your work as inhabiting? Are your pieces made be exhibited in a fine art sense, or used within a more every day environment by the people who commission them? Both – some people don’t want to assign a function to the materials I make, the samples are then framed and displayed. Other people want the materials I produce to become an object. At the moment, I’m concentrating more on fashion accessories as a field of application. Hairstylists also call upon my skills to participate in the design of hairstyles.

You mostly work with real human hair from private donations. How does this process work? I am solicited by private individuals for one-off orders. Other individuals spontaneously send me their cut hair without asking me for something in return. I use these donations to experiment with new skills. Finally, some designers or hairstylists solicit me for special orders. For these, it is often a question of working with synthetic hair or natural hair extensions, because the production is more consequent.

Is sustainability a central consideration of your work? The eco-responsible dimension of my project is implicit. I don’t communicate much about it but it exists. I try to valorise scraps that are often considered as waste. Within the framework of my research, these scraps get a second life in the daily life of their owners. In a subtle way, I help them to consider the result of a haircut as a precious material to keep and transmit. This fibre represents a fantastic conceptual and material starting point for creation.

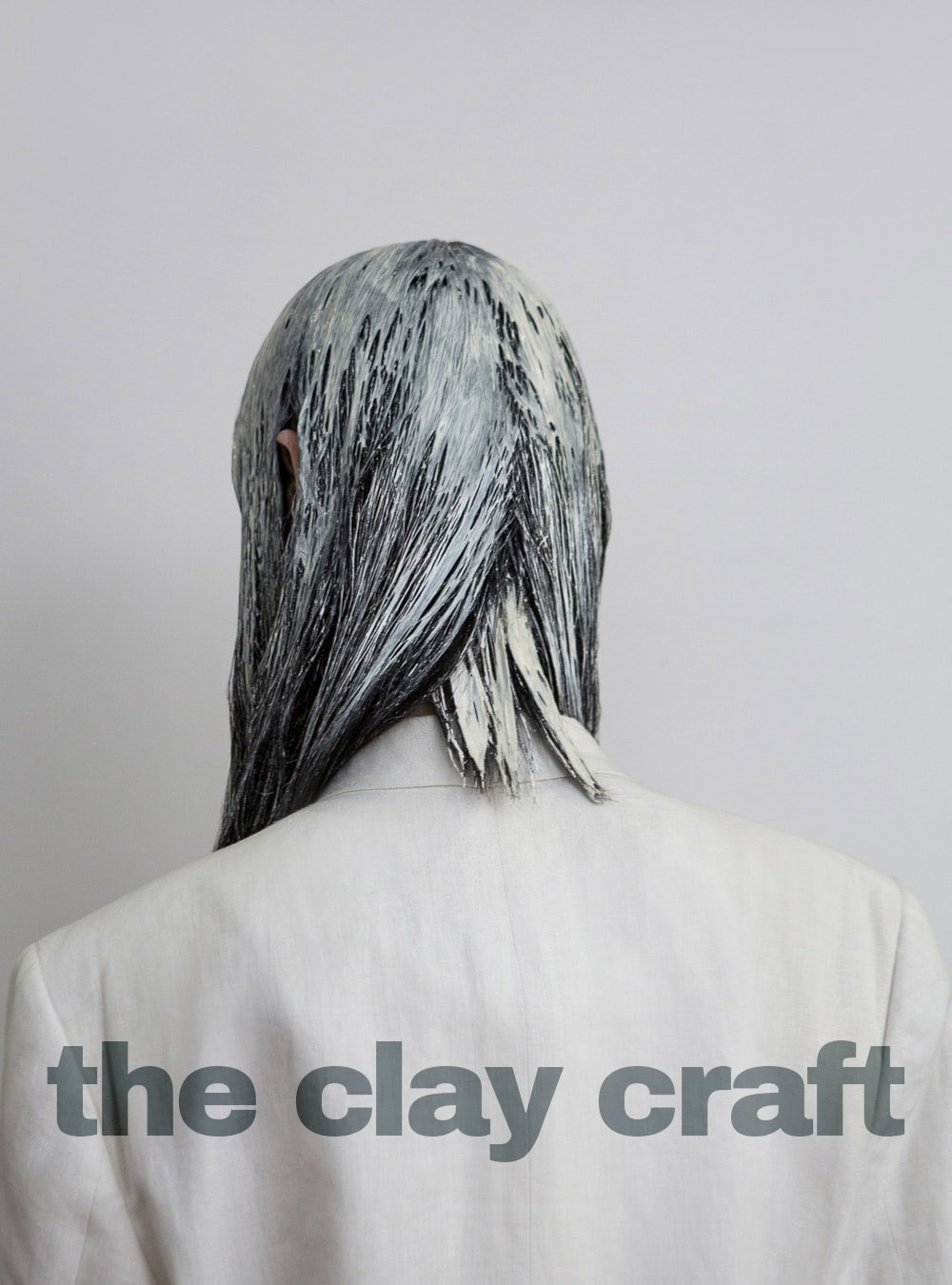

Can you tell me a bit more about one of the more elusive techniques you’ve used – the powdered hair pigment process? When I receive hair that is less than 5 cm long, I reduce it to powder. This powder is fine and homogeneous enough to become a textile screen printing pigment. This allows me to print patterns with the original hair colour. I can also vary the effects to obtain textures close to leather, but also fluffy effects.

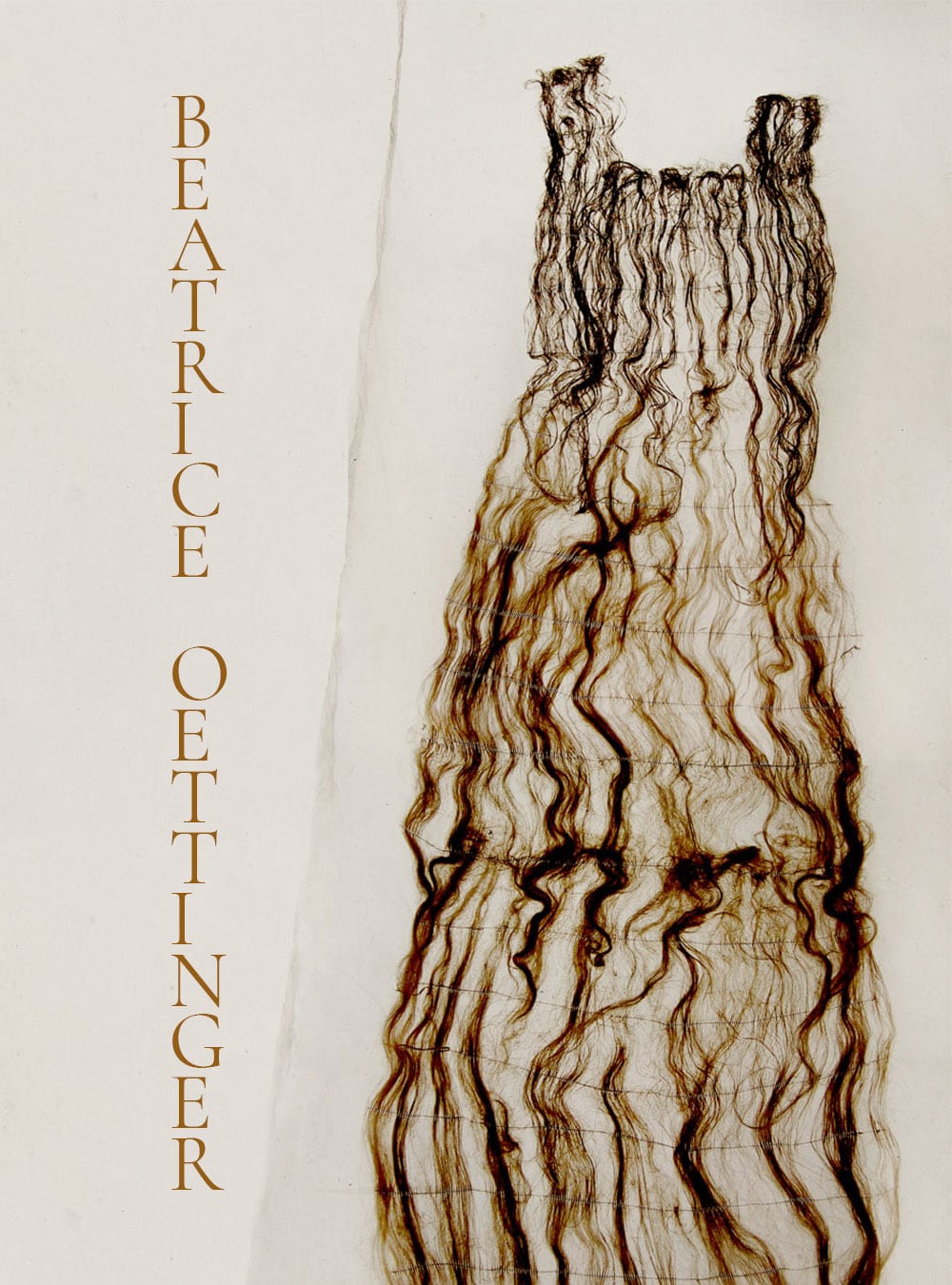

Out of all the techniques you’ve worked with, which has been your favourite so far? All the transformation techniques that I’ve done are interesting, because they just need to evolve and progress. At the moment I prefer hair weaving. This technique is often requested when shaping hair longer than 20 cm. Weaving allows me to play with the morphological and chromatic characteristics of each hair.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR