ART + CULTURE: Merryn Omotayo Alaka and Sam Frésquez discuss their individual and collaborative practices, which seek to amplify cultural histories

Interview: Hasadri Freeman

Art: Merryn Omotayo Alaka + Sam Frésquez

Photography: Steffi Faircloth, Merryn Omotayo Alaka, Josh Loeser, + Zoé Blue

Images courtesy of the artists and Lisa Sette Gallery

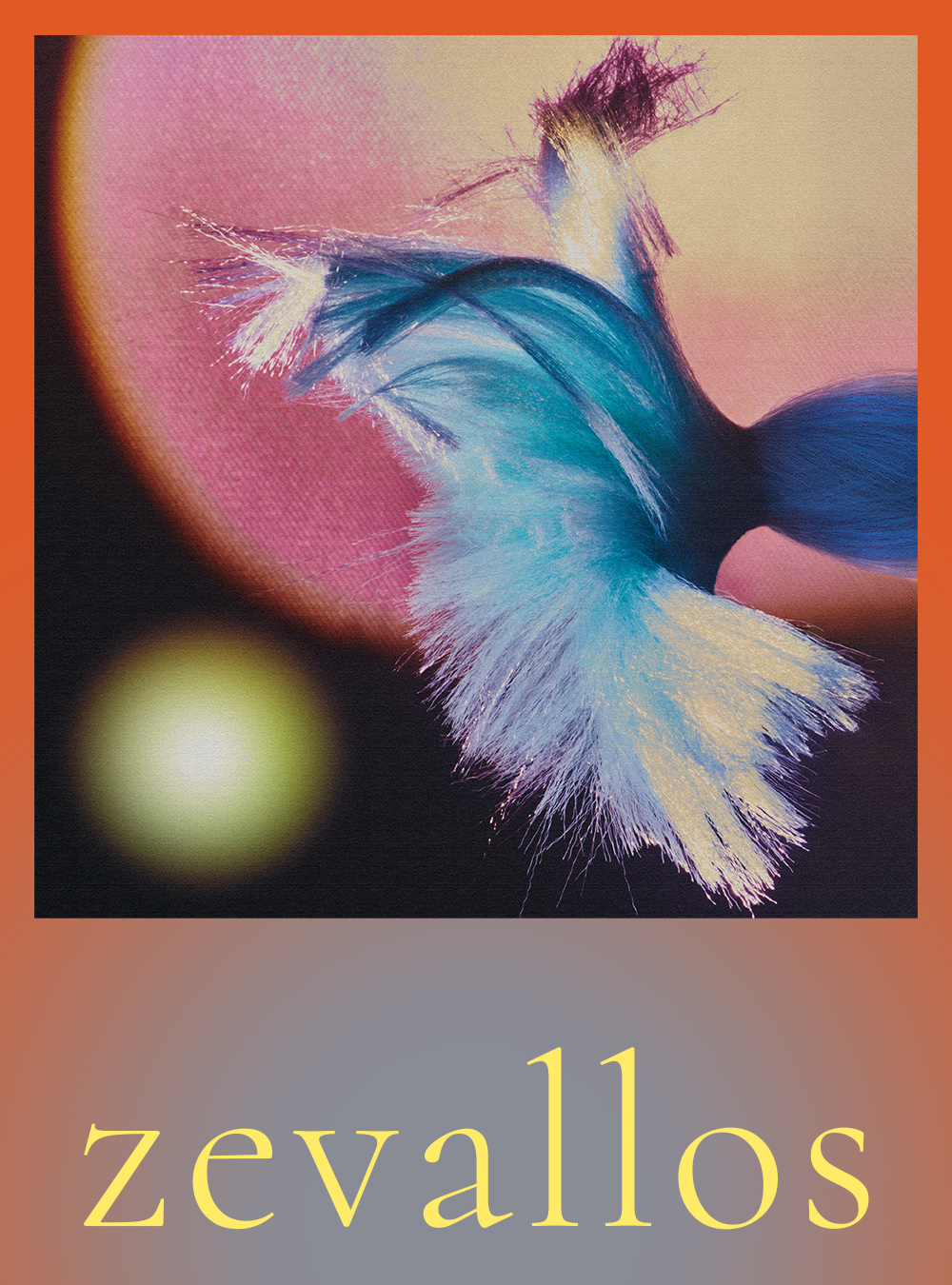

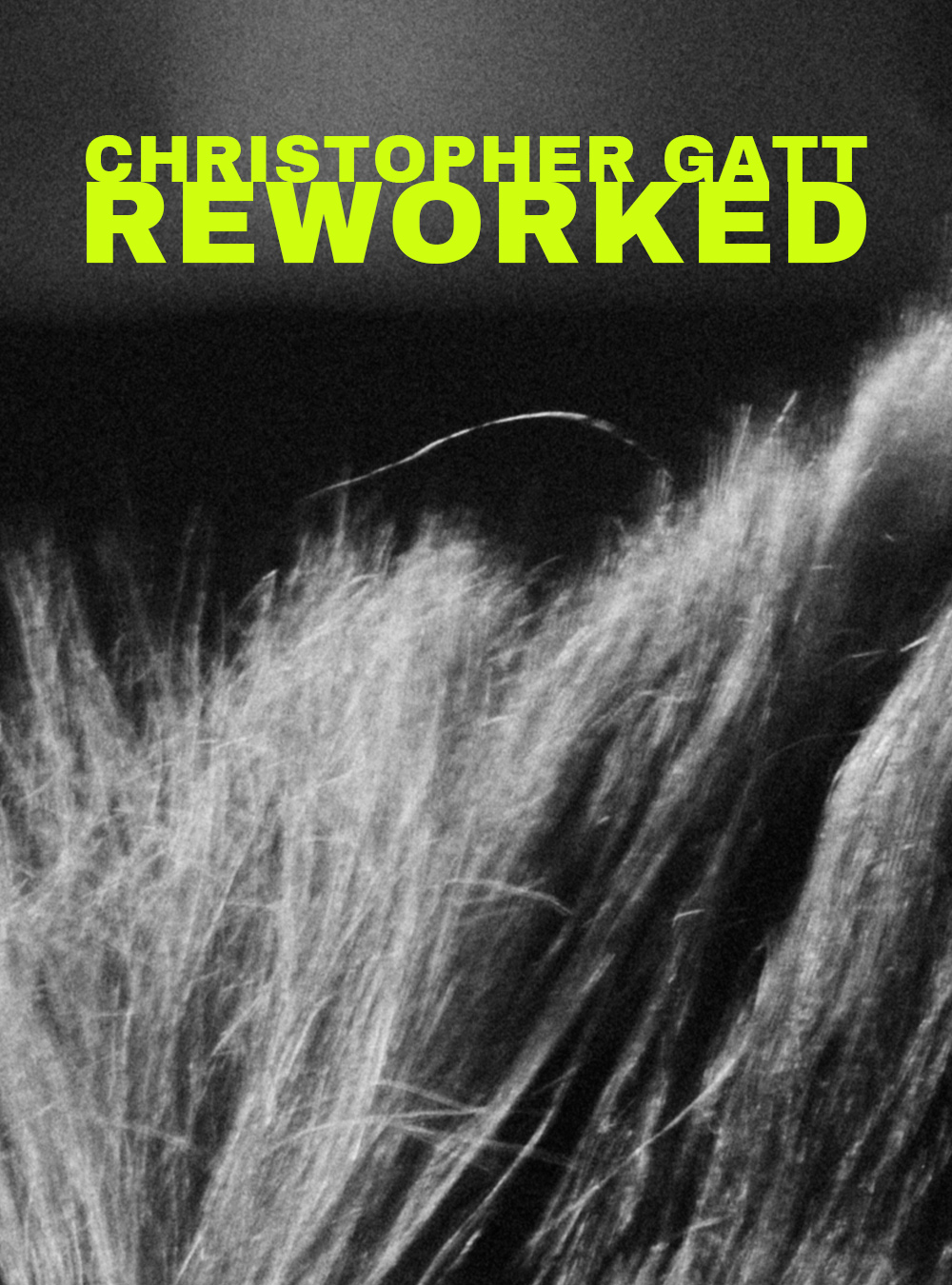

There’s an expansiveness to the work of Merryn Omotaya Alaka and Sam Frésquez, both in their individual practices and those projects they complete together. Mixing fibres, materials, and varied ephemera from their respective cultural histories, their individual practices work to find linkages between modern cultural artefacts and ancient history, such as a piece by the two that replicates a door-knocker earring in Brazilian gold granite. Based in Phoenix, the two artists met in art school and bonded over hair. As Merryn mentions, “Sam would come to class every other day with different hair—extensions in, or a really long, yanky ponytail—it felt like this ritual that we both understood and enjoyed as a mode of expression.” Collaboratively, they draw on that personal history through discursive, gigantesque installations out of hair that amplify the marginalised across multiple axes, the long-denigrated craft arts, and the hair histories of Black and brown women. Spatial foci that force attention towards these histories, the sculptures are “large, unapologetic, and unafraid to take up space…the bigger the room, the better.” In a contemporary art tradition that lately employs hair to deal with purportedly universal abstracts like abjection and immanence, they find equal narrative potency and universality in the things we carry—be it identity, pride, or trauma—in our hair.

M: I began to work with hair when doing my undergrad at Arizona State University. I was taking a fibres class and had a great instructor showing me artists that I might be interested in, like Sonya Clark and Lorna Simpson. I was really interested in the conversation that they were also creating with hair and craft art. Sonya Clark’s work was interesting to me because hair in her work was truly this representation of identity–it carries your DNA in a sense, so in references I wanted to reclaim my own identity: the parts of myself that growing up felt very suppressed. I am biracial, so my hair always felt like the representation of an identity I couldn’t feel fully connected to because racially I was black. I was constantly struggling to find my identity, place, and belonging.

I don’t have it anymore and I never photographed it, but the first hair sculpture/textile piece I made was this wide toothed orange comb that I’d had since I was a kid. I braided hair, wove it together, and draped it from this comb. It felt like this comb was detangling the racial trauma of growing up in this in-between world.

S: I think for most people, myself included, it’s a huge thing socially. Hair is always such a big part of how you present yourself and the way you show up in spaces you exist in from day to day. I always associate it with the teenage part of your life—trying to figure out like so much, and it all rides in your hair. It was always a big part of Merryn’s and my friendship and it was something that we always talk about. I think my first work with hair was a collaboration with Merryn.

M: We met at Arizona State University, in an art history class. Sam would come to class every other day with different hair—extensions in, or a really long, yanky ponytail—it felt like this ritual that we both understood and enjoyed as a mode of expression.

S: We were taking a class called ‘Women in Visual Arts.’ It was a very intense art history course, so we’d make these huge stacks of notecards and just stay up and study together. And I think that’s also how we realized we worked very well together—we were already talking about the ideas we were interested in and the work we were interested in. For both of us, it felt like such a wild thing to go to school and only be taught about white men, and then think “Oh, I’m going to take a class on women in the arts,” and then you go to that class and it’s practically only white women. You’re like, “damn, when are we going to get to my ancestors?” It was a big point of connection which we discussed a lot in our friendship, so our collaboration came about very naturally.

M: Yeah, I would agree it was very natural. I feel like we complement each other in the way we work, and our thinking style feels very fluid. The first work we collaborated on was It’s Mine, I Bought It. It came about because Sam had some funding—technically it was our second collaboration, but this was the first one on which we were truly combining our ideas and both acknowledging our own backgrounds and experiences with hair to develop a broader conversation about hair across cultures. The first installation embodied tassel forms. We were researching objects and fiber artists went into this deep dive on the historical use of tassels. In Ancient Egyptian cultures, they were used to ward off spirits, and in the Catholic religion, they’re worn on garments to set hierarchies.

Functionally, tassels were used to contain fibres together. So, we wanted to create this parallel narrative with hair. Hair is also a fibre material that holds us together, that becomes part of the social hierarchy—especially for Black and brown women. Anything you want to add, Sam?

S: I think scale is an important part of our work and always has been, especially in our hair work. I really like that our work feels like a person. A lot of the time, they have this presence because they are so large, and it’s as if somebody has their back to you, that they’re about to turn around.

M: Creating a physical reaction to the material, a material that’s so natural and part of so many people’s rituals. It’s so interesting to create an environment with that. People always want to touch it. Its like the hair is a magnet. There’s something instinctual about it.

S: It’s a very intimate material. I think that some people think that it’s gross and I think that has also dictated how we use it a lot of the time—we try not to steer into the “grossness.”

ON CRAFT + MATERIAL

S: We are both drawn to craft as a medium in general, but not necessarily hair craft. I don’t know a ton about hair craft specifically, but craft in general is important because it’s typically seen as gendered labour, labour that—

M: Labour that historically, brown and black people have been used for. Even today, we feel that line between craft and fine art. The question arises, is craft art viewed differently because of the genders and races with which it’s associated?

S: And class…Individually but together as well, we usually start with “what do we want to talk about, and what do we want to use to talk about it?” Individually it starts with asking myself that question, and then I decide materials.

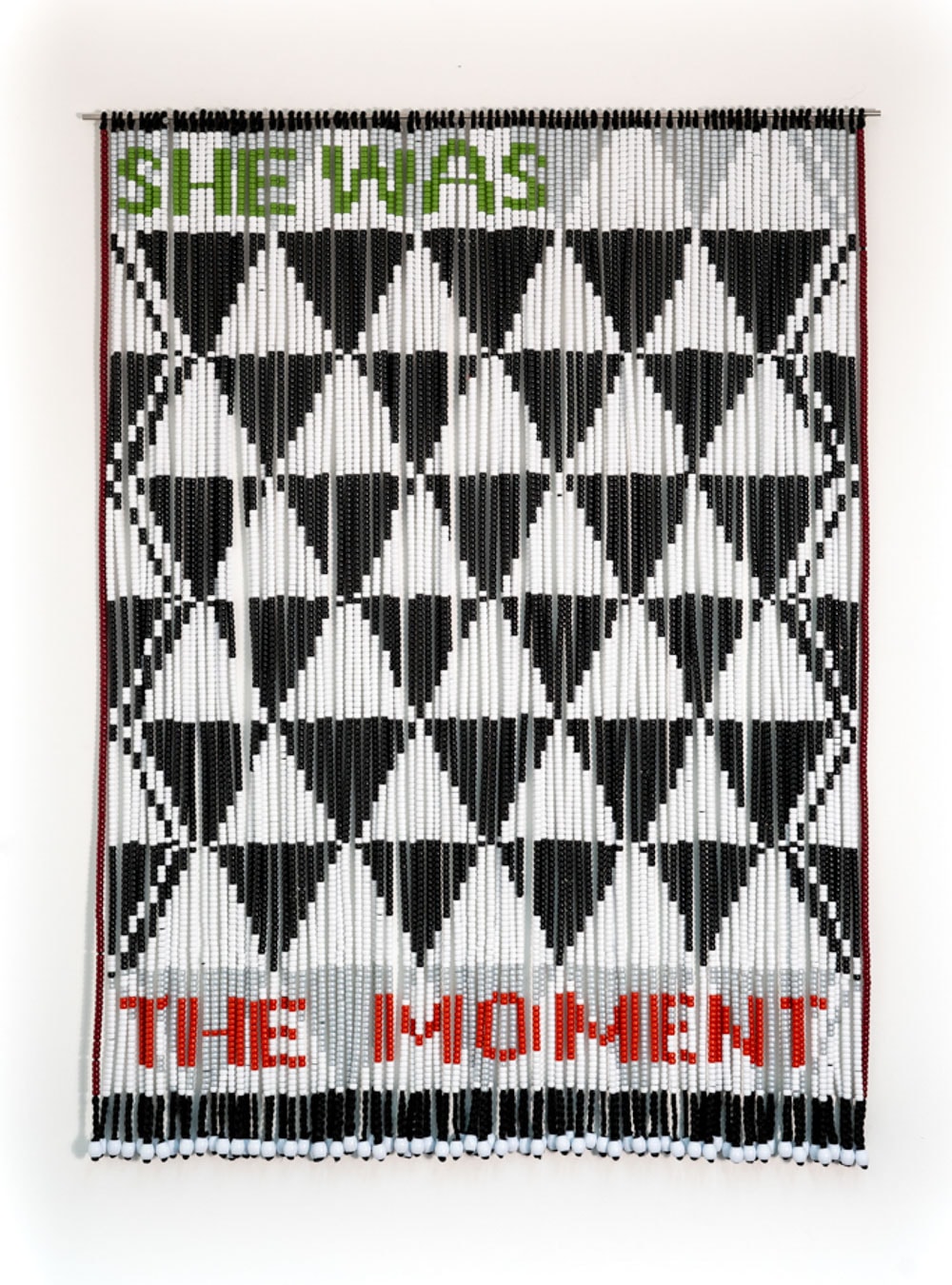

M: Within my individual work is also a conversation about discerning the cultural significance of materials. I can pull from those histories and leverage it to talk about contemporary things and trace ideas through history. For example, my beaded hair pieces, Snatched!, Lead with Your Looks, The Moment—with those works I was really pulling from the culture of hair for Black women, and specifically women in West Africa, as my dad is Nigerian.

M (ctnd.): I was interested in using braided hair as a discursive material to talk about forms of protection, because in African cultures there are so many hairstyles that are simultaneously used as adornment and protection for the structurally fragile nature of black hair. That’s why we get the term “protective style.” I was relating it to the present day, where it still feels like a form of protection. In the forms they took on, I was really influenced by beaded sculptures and beaded objects associated with West African culture. There’s really intricate beaded crowns that are also forms of protection, so that was another place where the material was emerging from a historical perspective. But there, I was playing more on a contemporary use of beads. I used pony beads, which you would find at the beauty supply store.

But there were elements of protection in an emotional sense, too. For me the work was emotionally driven by vulnerability. You try to protect yourself in whatever ways you can, and there is something about hair…for me it has felt like a shield in some ways—you can hide behind it like a mask, because it’s so big. I don’t know if in West African culture if it was also used as an emotional form of protection, but I know that the work I was making was intentionally imbued with that idea.

S: My work Cielito Lindo uses mariachi pant buttons. The history of mariachi pant buttons is really interesting: the whole charro outfit is the outfit that mariachis wear. It originated when what is now Mexico was colonized. Indigenous Mexicans weren’t allowed to ride horses and when they finally were, they had to wear this outfit that differentiated them from afar. It’s funny because it’s still a derogatory term, but was even more so at that time. The etymology of the word, I think, means “person who speaks roughly, person of the earth, person of bad taste.” And now it’s this national outfit, an iconic Mexican thing, which I feel is just fucked up. It says a lot about the world.

I think a lot of my solo work about presentation has stemmed from visual conversations and what we communicate visually to the people around us. How am I communicating, visually, to everyone, and acknowledging the history of the American Southwest, especially here in Arizona? Phoenix, AZ is very, very white-washed in a way that a lot of other places in the Southwest aren’t. In New Mexico and Texas there is a lot more geographical acknowledgement of the history of the land, that this was Mexico. But in Phoenix, it’s as if everything was built to erase and ignore that fact. I was born in Mesa. My family were a part of the people in Arizona before the Mexican-American war, and the border crossed over us, so we never immigrated. I am currently working on a large public art project, where were I’m making giant mariachi pant buttons that attach to the corner of a building.

THE THINGS WE CARRY

M: There was a big lapse of time between The Things We Carry and It’s Mine I Bought It, but we were drawn to a similar conversation, elaborating a bit more on class and presentation, gender and sexuality. The scale was much larger, but we were also referencing forms of chandeliers, to discuss how, often as a woman or a person of a marginalized gender or sexuality, there is not always space to take up in an environment, or to confidently enter spaces that are historically unwelcoming, white-washed, or just full of men. It was about reclaiming those spaces and making pieces that were intentionally focal points to claim attention.

S: It was about the feeling of being in a room and having someone look at you and then turn their back to you because they think you’re probably unimportant. This work was large, unapologetic, and unafraid to take up space. In the autumn, we are going to have a show at the Phoenix Art Museum, and it will be a very large room. I think we are both extremely excited to be able to fill that space.

M: Our work is very much an inflation, so I’m interested in getting into playfulness and curiosity.

S: Yeah, I think the bigger the room, the better.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR