- Nora Aurrekoetxea

- Nora Aurrekoetxea

- Nora Aurrekoetxea

ART + CULTURE: Nora Aurrekoetxea Etxebarria interrogates the function of structure without ornament in hair-constructions that consider aesthetic pleasure a crucial facet of structural integrity

Art: Nora Aurrekoetxea Etxebarria

Interview: Hasadri Freeman

Photography: Ander Sagastiberri, Alkesanndra Belz Rajtak, Ignacio Barrios, Pablo Gómez-Ogando, + Tycho van Dijk

Special Thanks to artistic collaborators Milena Diekmann + Kamila Wolszczak

“What if desire was the criteria to produce, organize and structure architecture and space?” That’s the question Nora Aurrekoetxea Extebarria poses with her sculptures, simultaneously reminiscent of ornate hair cultures and industrial society at large. Considering the juxtaposition of biological and manmade materials, she gathers crucial debates and contradictions surrounding the value ornament and pleasure hold to the built and ‘functional’ environment. Can desire and enjoyment be facets considered integral to design, rather than adornments or finishing touches? Employing hair in reference to its global use as a craft material and its refusal to be categorised as simply either structural or ornamental, Aurrekoetxea Extebarria posits that pleasure and ornament be considered as fundamental to the architecture of human societies as the structural integrity of our built world.

You use a variety of media in your sculptural works. When, why, and how did hair first enter your practice? I think the first time I made use of hair I my art practice was during my Erasmus exchange in Wroclaw, Poland. At that time, I was looking at hair—specifically facial and body hair—through a gendered lens. We would glue our own hair onto our faces and take pictures. It was closer to performance work.

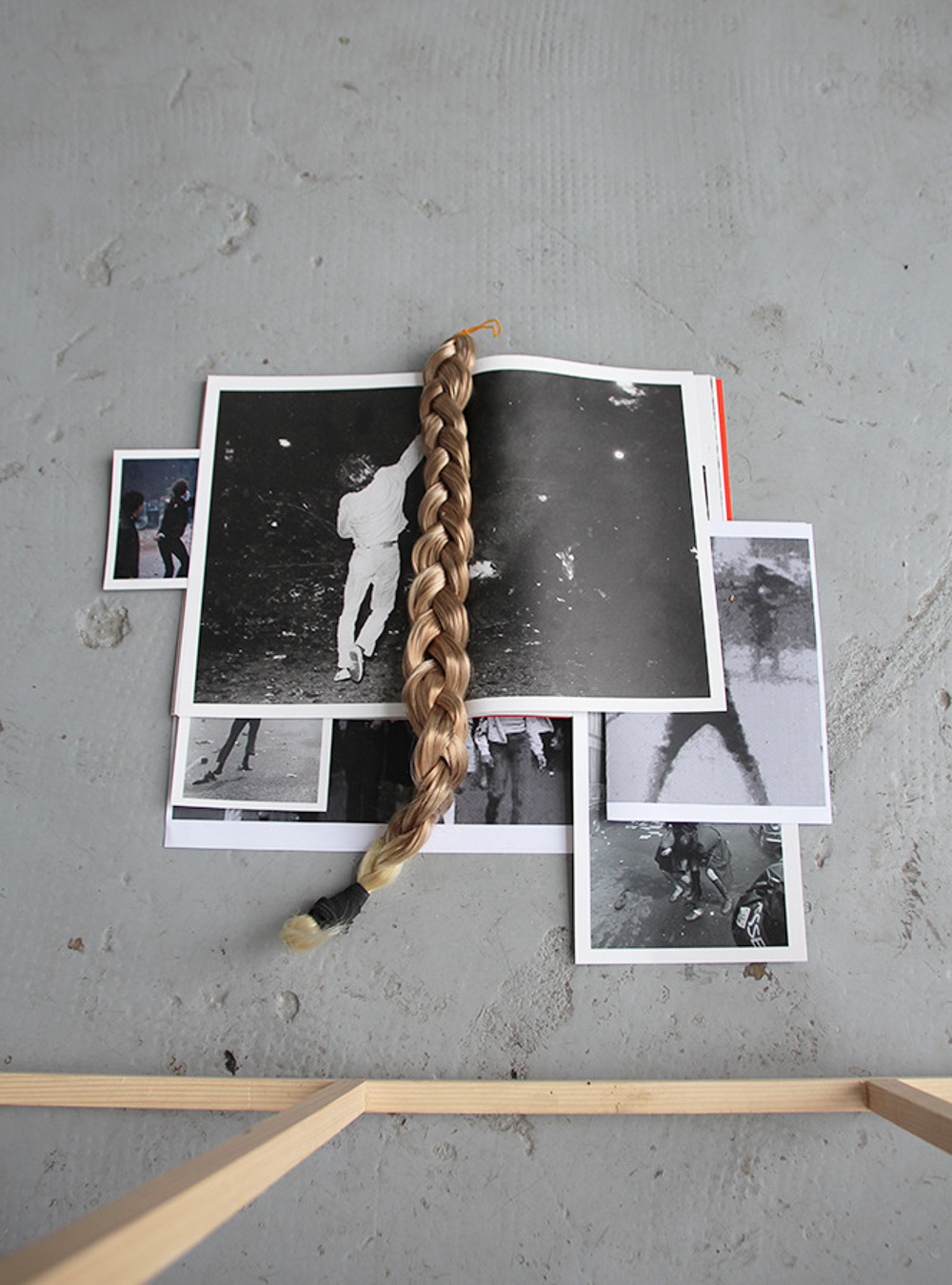

It wasn’t until 2018 during an art residency in La Cité Internationale des Arts in Paris that some synthetic hair extensions captured my attention. It reminded me of the long, braided hair cut and hidden in my grandma’s wardrobe, or a collection of hair fallen as waste on the floor. But when organized in a certain way, e.g., braided, they not only achieved a recognizable aesthetic form but also a self-sustaining structure.

So, I bought couple of hair extensions and did some tests. Everything that came after this was related to biographical events; I’ve cut my hair and used it as a prop for a bronze cast, named the blonde sculptures after my blonde friends, and much more.

It was 2019 when after re-watching the same YouTube tutorials about braiding and failing constantly that I found @hairstylist.dream on Instagram while looking for inspiration: Milena Diekmann, at the time a 16-year-old master of braiding based in Germany. And that’s how our collaboration started. We first made “MILENA” (2020) and “AULKI BAT” (2020) and this year had the chance to meet up again and work together on “DIVA” (2022).

As a material that’s largely been employed within a craft arts tradition, what dialogues have you encountered when bringing hair into the traditional gallery space? The action and gesture of braiding was the main connection I found at that time with craft art—it was almost like weaving, making knots. With hair, the thing is that the same gesture completed by another material would have a use, a practical function further that the aesthetic one. Furthermore, it would be considered a highly regarded craft, but as far as I know, hairdressers have not been yet properly recognized as such. The main exercise for me was to treat hair extensions as any other material with which I could create a pattern, a structure, a form, a shape, like I could do with ropes or fabric. I was obsessed with learning different techniques for intimate gestures of care and proximity.

I discovered Adolf Loos´s lecture-essay “Ornament and Crime”. And this text was the beginning of my interest in the conceptual debate between ornament and structure. It became an iconic text in architecture and constituted a radical approach by advocating for the abolition of ornament. His repulsion towards adornment was not aesthetic but cultural, representing his “opposition to waste, the ephemeral and the frivolous.” It was a moment of transition away from an artisanal to an industrial mode of production, the industrial revolution. He argued that the progress of culture was associated with the removal of ornaments from everyday objects and it was “a crime to force craftsmen or builders to waste their time in ornamentation.” He asserted that the ornament was not something that naturally emanates from objects, but that it was something artificially attached that can thus be dispensed with.

William Morris was an English architect, designer and textiles teacher, poet, and socialist activist would point to the contrary. Associated with the British Arts and Crafts movement, he was one of the main promoters of the renaissance of traditional textile art; preserving, recovering, and improving artisanal production methods in the face of industrial and chain production. For Morris, there was a principle of pleasure linked to ornament, and he affirmed that this was one of the reasons why we had never given the “task added to the necessary fundamental work” in making a functional object a thing of beauty. He believed that people should be surrounded by things that were “beautiful and well done.” Both thinkers find their idea of pleasure in opposition to the other; the enjoyment for Morris lay in the work on the ornament, while, for Loos, it was in its removal.

This idea of pleasure and function was what triggered my research on braiding in metal structures. For me the ornaments have a structural function in my daily life, understanding structure as the mode by which we organize and build things around us. However, structural can also be understood as fundamental or necessary. What would happen if structuring our surroundings was based on pleasure and desire? My aim is to work with the ability to transmit symbols constitutive of the Ornament, incorporating desire as a need.

You also employ a juxtaposition between more delicate elements and harder, industrial/practical materials. Would you define hair as the latter, former, or both, and why? It is definitely both. And that particular property of hair intrigues me the most. I look for this opposition unconsciously in the use and combination of materials, and it is only later that I can see the contrast that this implies.

You’ve incorporated hair in its original, soft form, but also in a cast metal form. How do these material representations differ for you in what they communicate about the original signified? Do you choose to work with a hair representation first, and then choose the form, or does the process happen more organically? Every time I depart from a real object, the following materialization consists of reaching further from its original form through simple gestures and operations; transforming it into something else, something that is unpredictable and unknown. Repetition, isolation, inversion, juxtaposition, division… these are some of the interventions that allow me to see the original object through different lenses, far from its original signified. The primary meaning disappears and new signification arises. It is like learning to see for the first time, with fresh eyes, like a kid.

What is your dream hair project? I remember during my BA in the Basque country, a teacher of sculpture said, “that, what you are wearing in your head, that is making sculpture.” He was pointing at a fabric covering my classmate’s head. That image lodged in my head, and now every time I see hairstyles or braids… I can also see them as sculptures detached from their bodies, like empty shells.

This summer I will be an artist-in-residence at Paradise Air in Matsudo, Japan, where I will be studying traditional Japanese hairstyles and contemporary use of wigs. I will be researching different ways of hardening hairstyles in order to disassociate them from the head/neck structure.

I don’t think I have such a thing as a dream project, but I am definitely passionate about learning traditional and contemporary techniques of treating, caring for, and manipulating hair. Knowing more about hair, how to create space, shapes, and forms with it to incorporate in my sculptural practice would be my proximate desire.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR