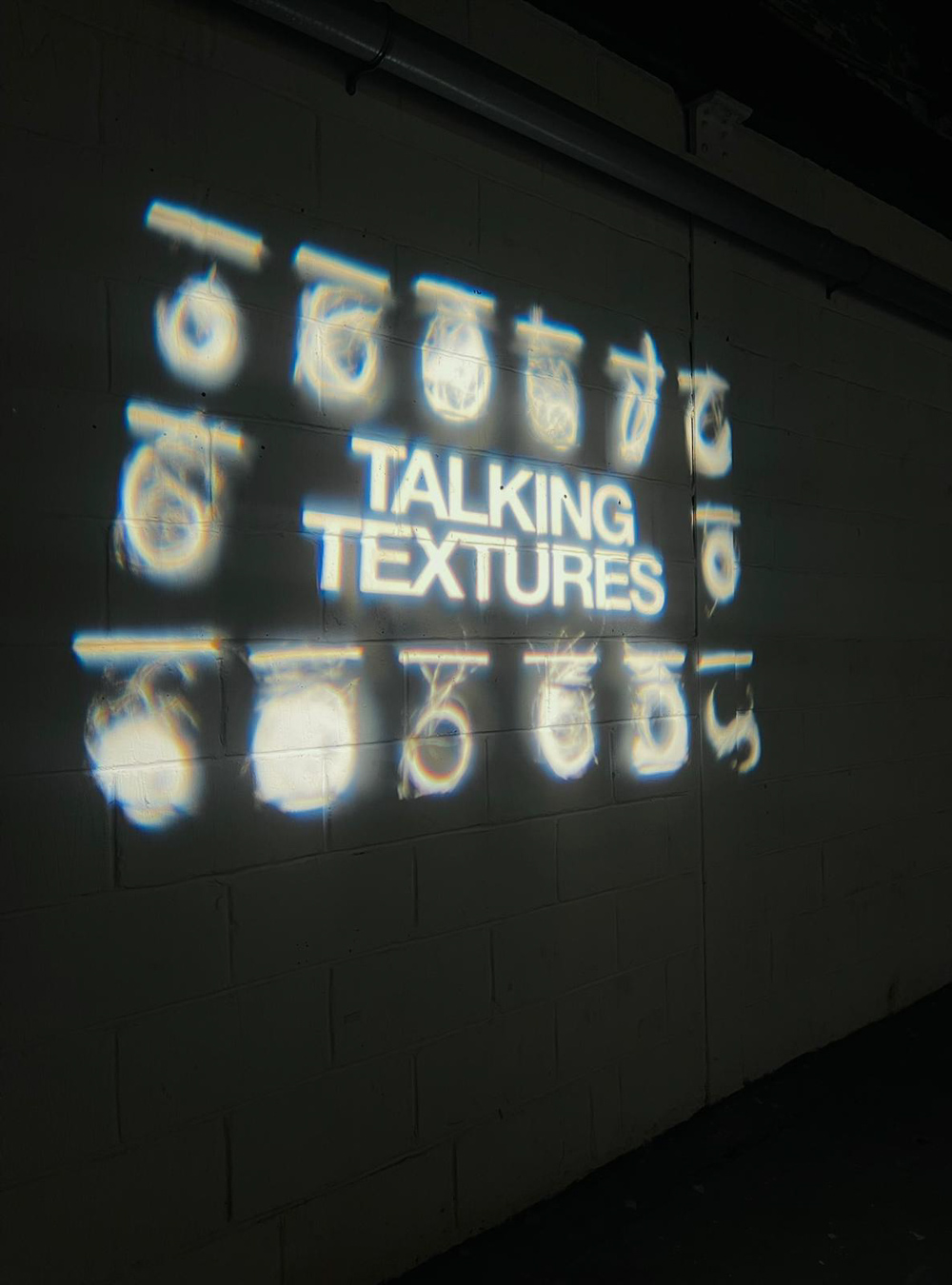

ART + CULTURE: INFRINGE catches up with Yasemin Hassan and the rest of the team behind Talking Textures, an immensely collaborative exhibition highlighting hair histories and experiences within SWANA communities

“I’m just warning you, my public speaking skills are a bit iffy.” Yasemin Hassan says by way of introduction at the opening night of Talking Textures, before her panel discussion. “I’m a hairdresser, so I’m much better one-on-one.” Almost immediately, she also notes that the film we’re watching, Barbershop Chat, a forum-style discussion inside a hair shop created in collaboration with videographer ABDULISMS to tap into the sense of community lost in Western salons, is played on a 1-hour loop–“the length of a haircut,” she points out, proudly.

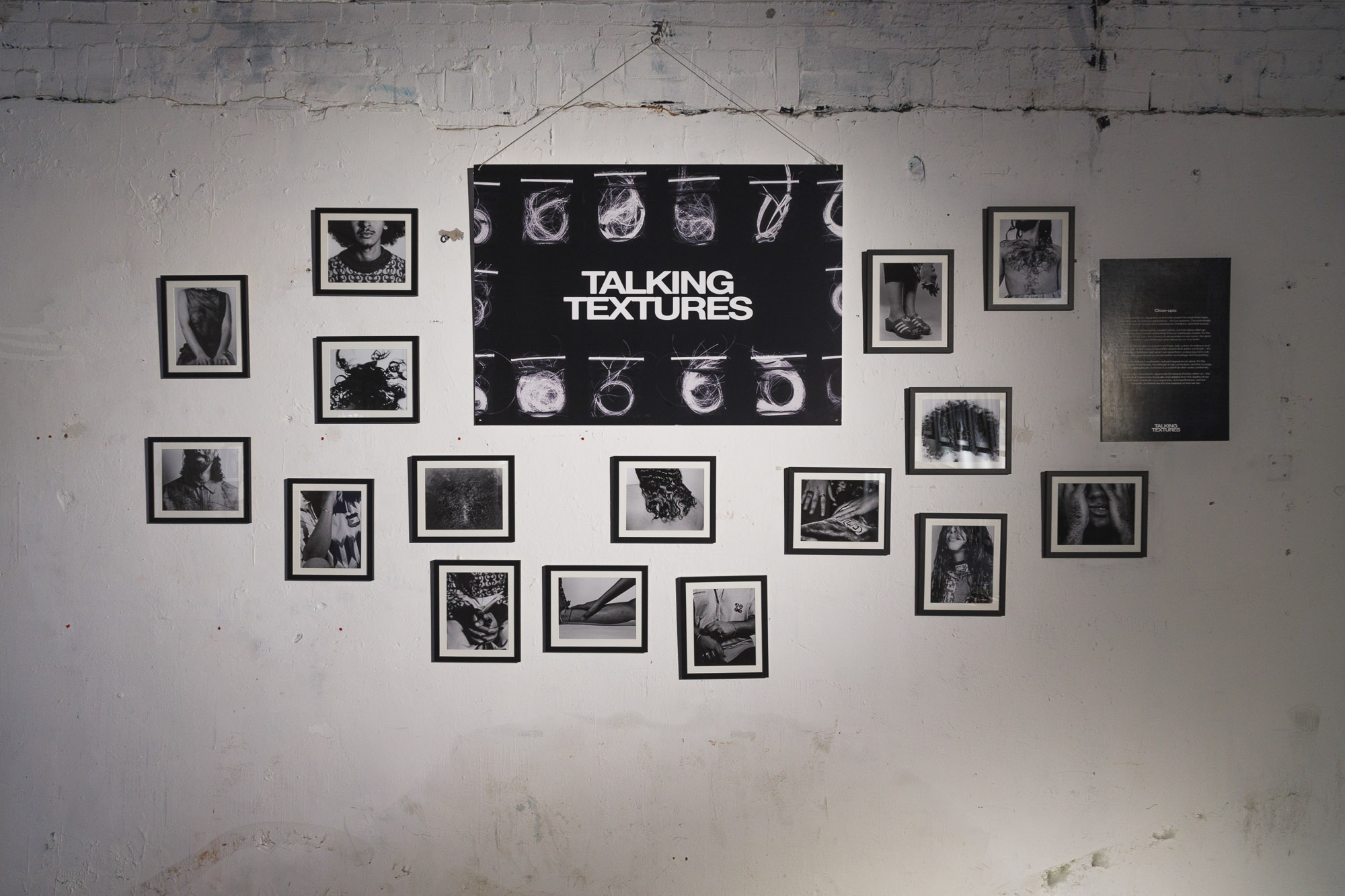

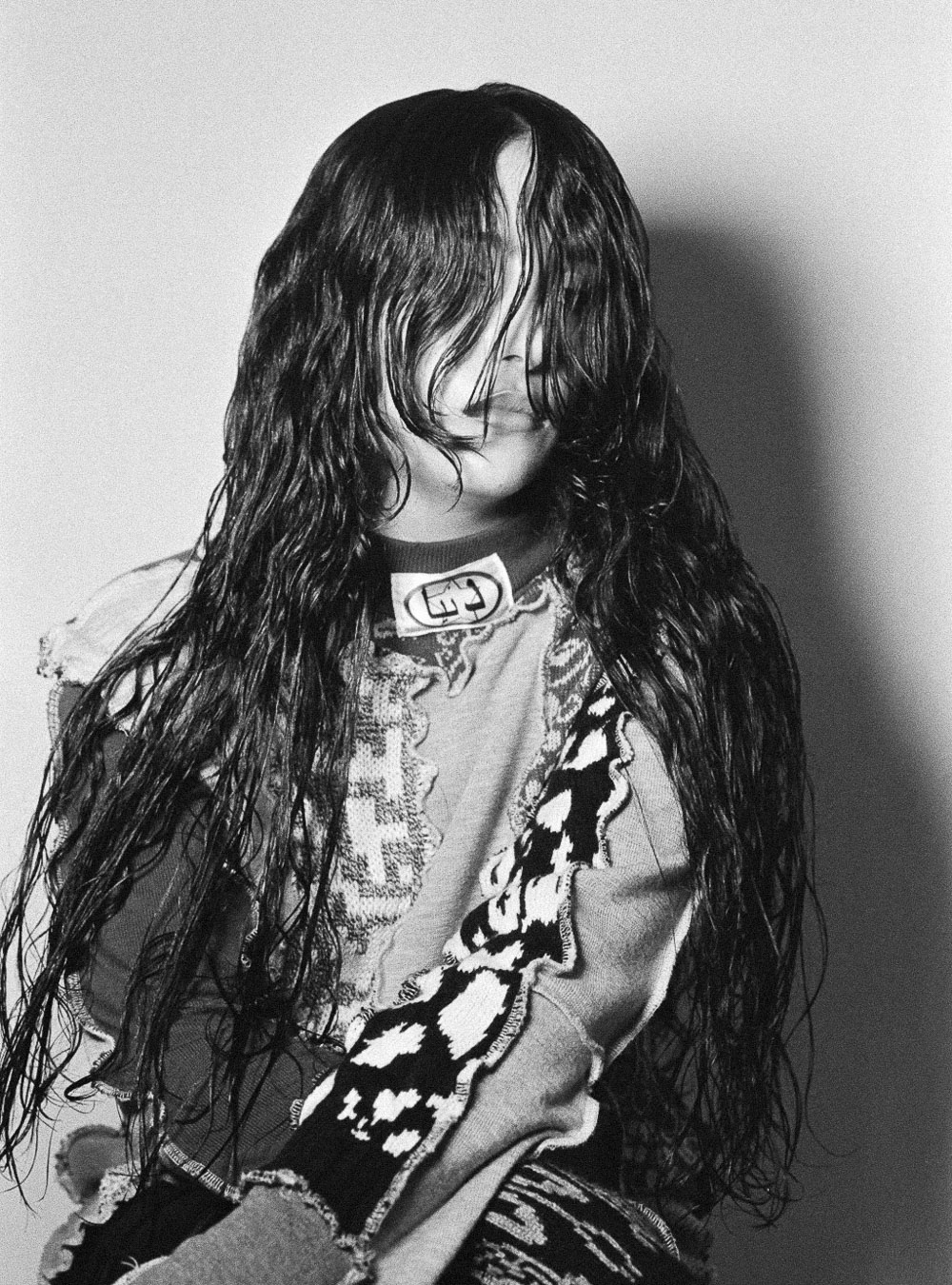

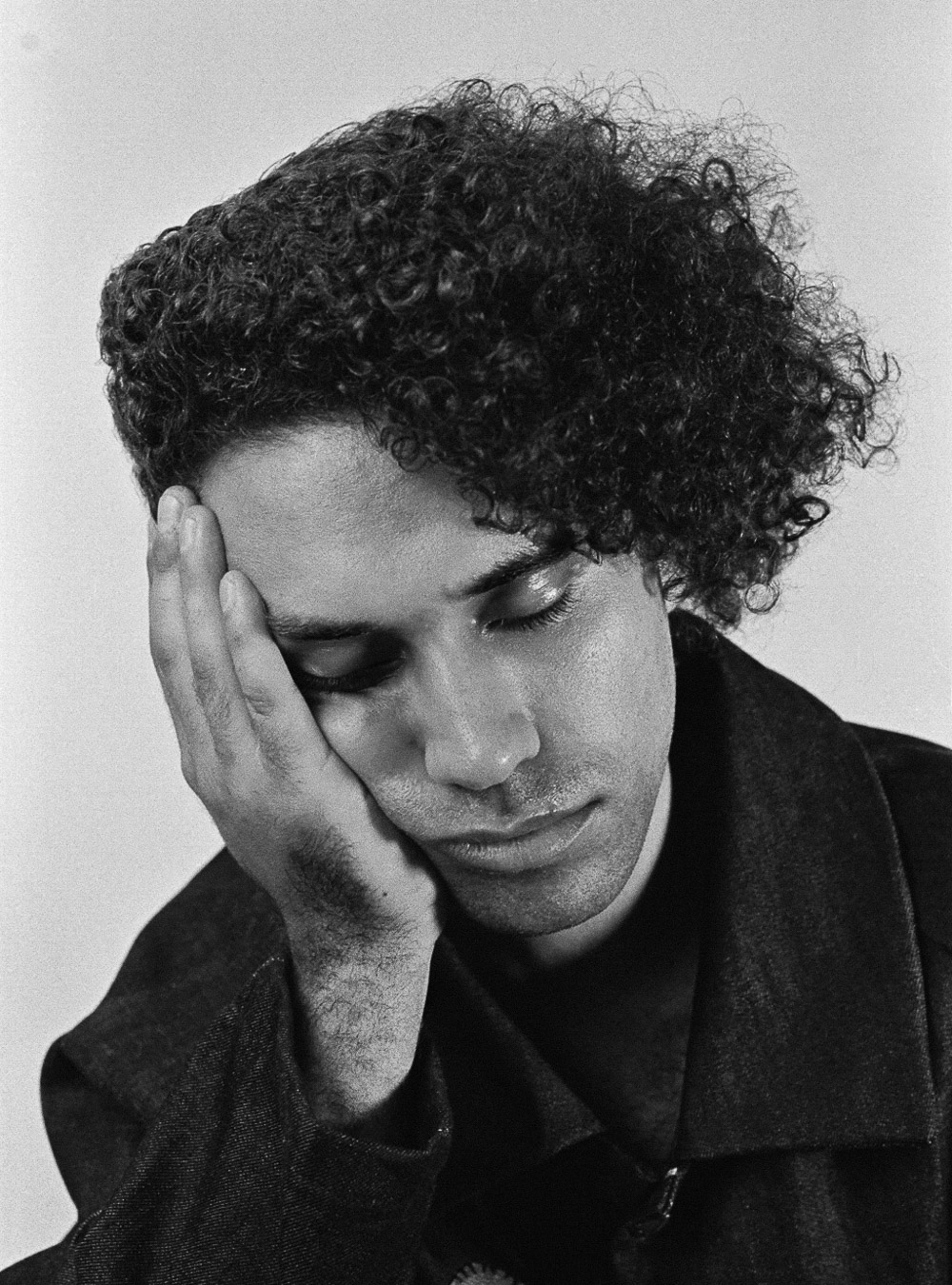

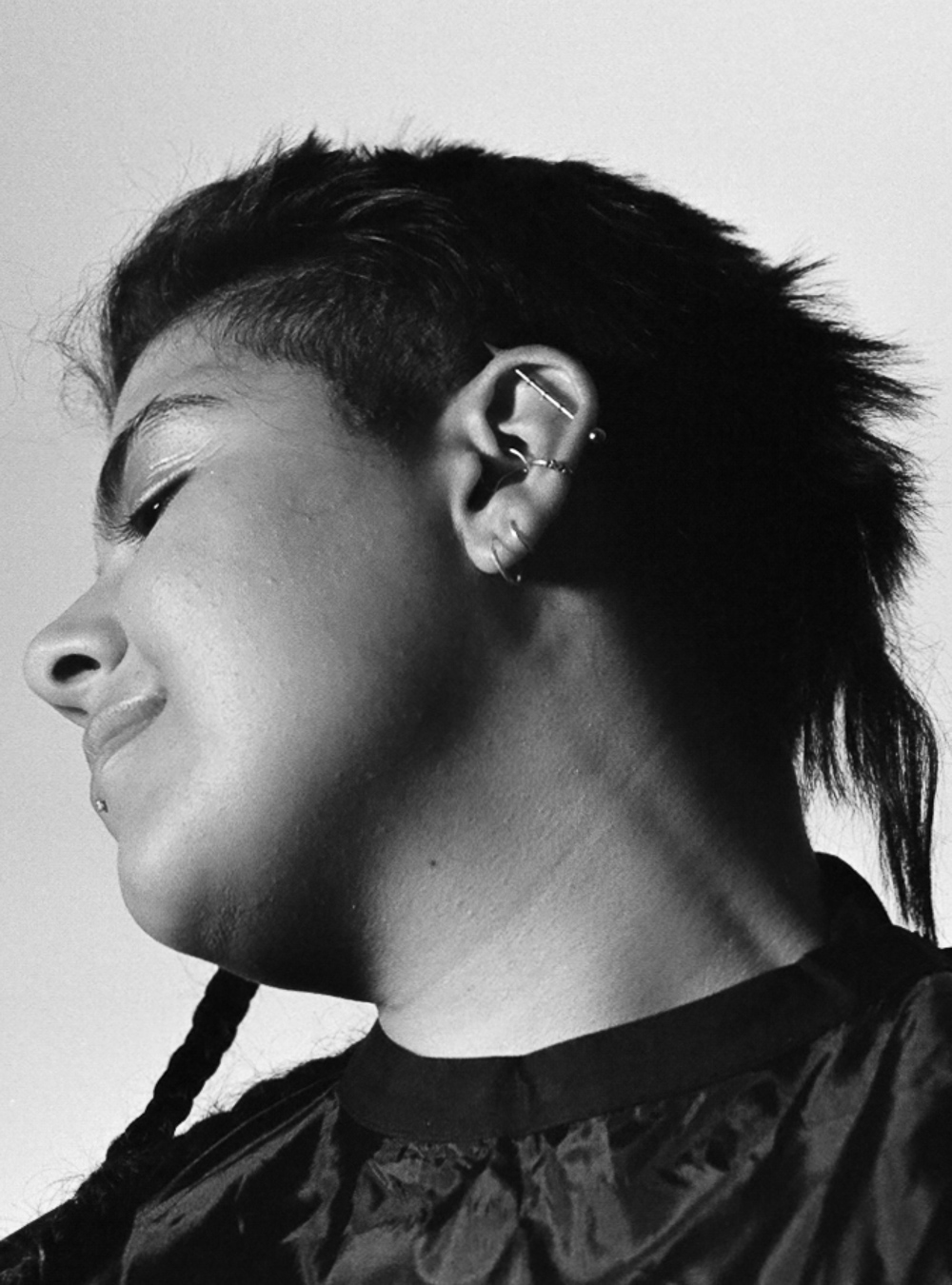

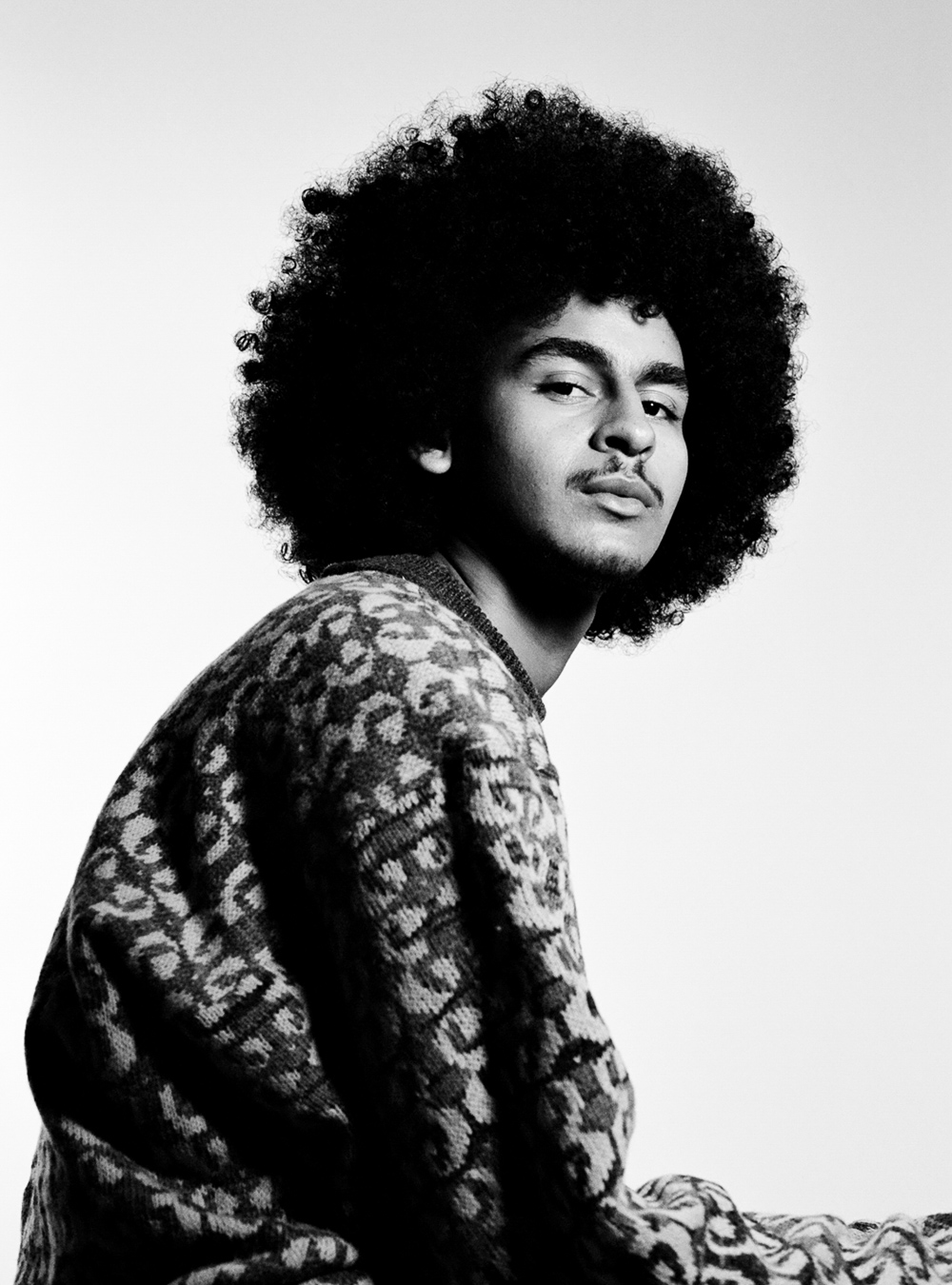

While hair is certainly the genesis of the exhibition, which seeks to amplify discussion around what Hassan calls the diverse “in-between” textures prevalent within SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) communities, the final product of two years of work culminated this past weekend in a veritable who’s who of up and coming voices in SWANA fashion, hair, art, and media. Collaboration abounds–whether it’s tagging in stylist Dania Arafeh and her platform 3EIB, a fashion platform dedicated to promoting and presenting SWANA designers, or tapping Dalia Al-Dujali, the founder and editor of The Road to Nowhere magazine covering “culture through diaspora” to lead the enlightening panel discussion around which the party unfolds. And we can’t forget photographer Yeliz Zaifoglu, who breathes tenderness into each careful image, or writer and panelist Alya Mooro, whose cheerful curiosity invites newcomers despite her own highly educated background in journalism. “I just discovered the term ‘global majority’ the other day,” she mentions during the panel. “And we are the majority…so why does it feel like [our hair] is treated as a niche?” There’s also the punky Trina, whose client-first mindset and conversation-starting observations about intra-community hair judgement calls back to the discussions looping on video in the exhibition room. “[As a hairdresser], if I can’t do my mom’s hair, what am I doing?”

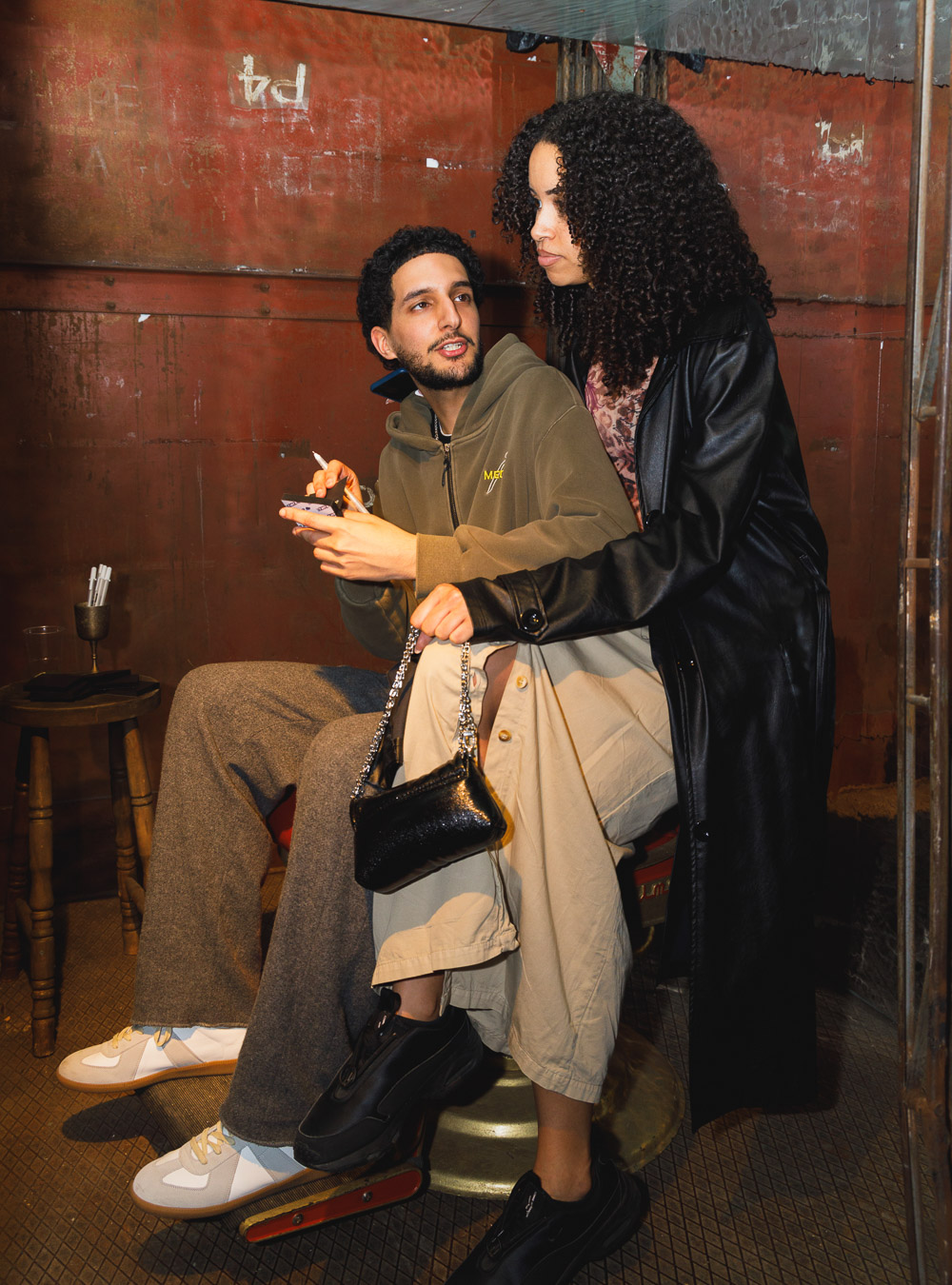

The exhibit itself is detail-oriented, but the teams’ aesthetic approach could be encapsulated in the seating: most places to take a seat are on carpets boasting traditional designs, or in a salon chair. ‘Fine’ and ‘craft’ art approaches are also intertwined, with the sterility of single channel video booths, projection video, and cleanly mounted photography softened by red lighting, carpets, couches, and pillows (a welcome break from the blockish gallery bench), beaded curtains, and a spread of SWANA delicacies, in addition to a mix of live performances from musicians berkeğim and Rama Alcoutlabi and club tunes from DJ and sonic archivist ZAYTOONA. Attendees have their tarot read by Ayshe-Mira Yashin or henna applied by mehndi painter and creative healer Jenna Anne Nathan, and the night culminates in an effervescent performance by drag performer Tahini Molasses. It’s experiential, with artistry from the region on full, unbothered, display.

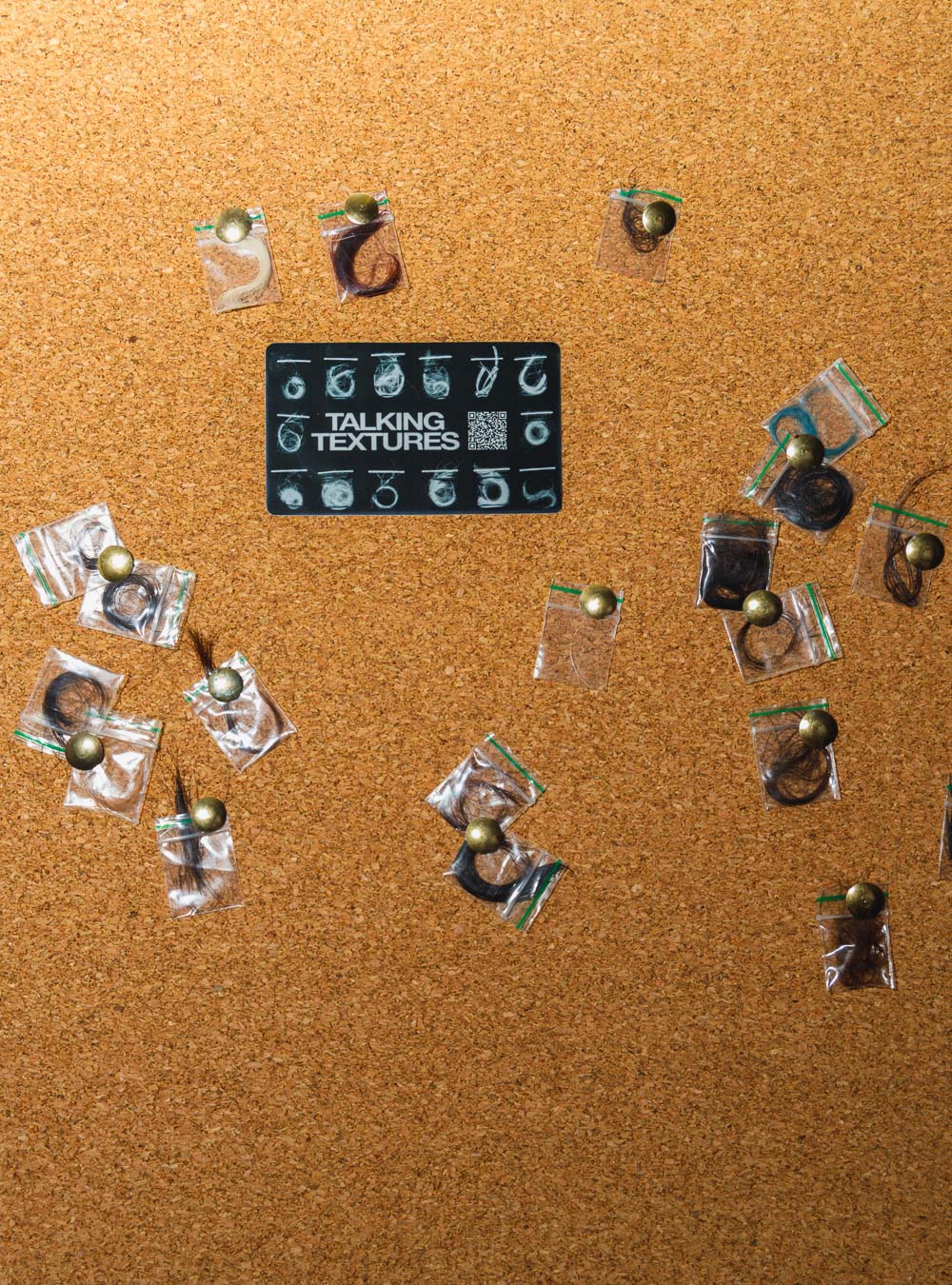

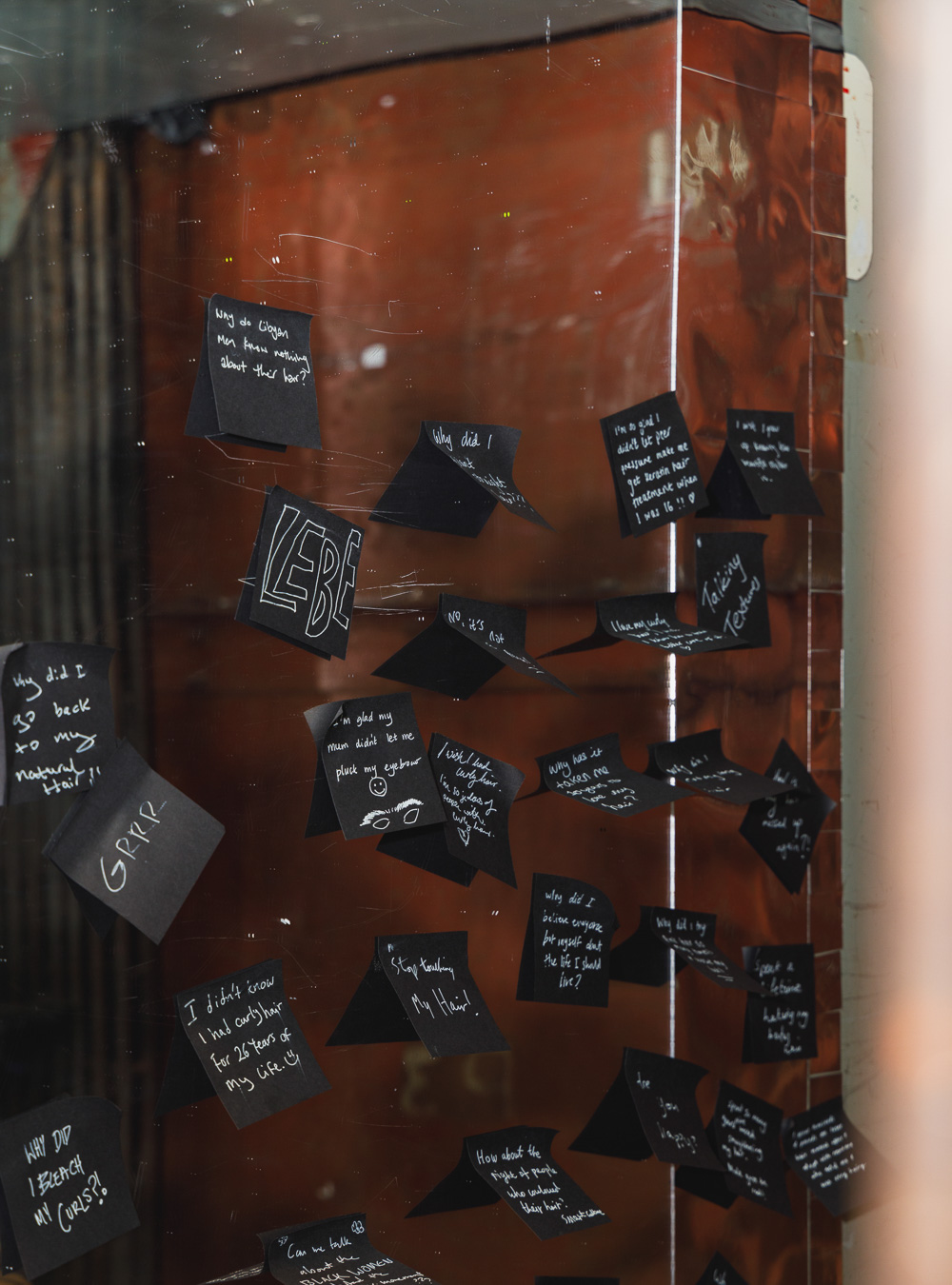

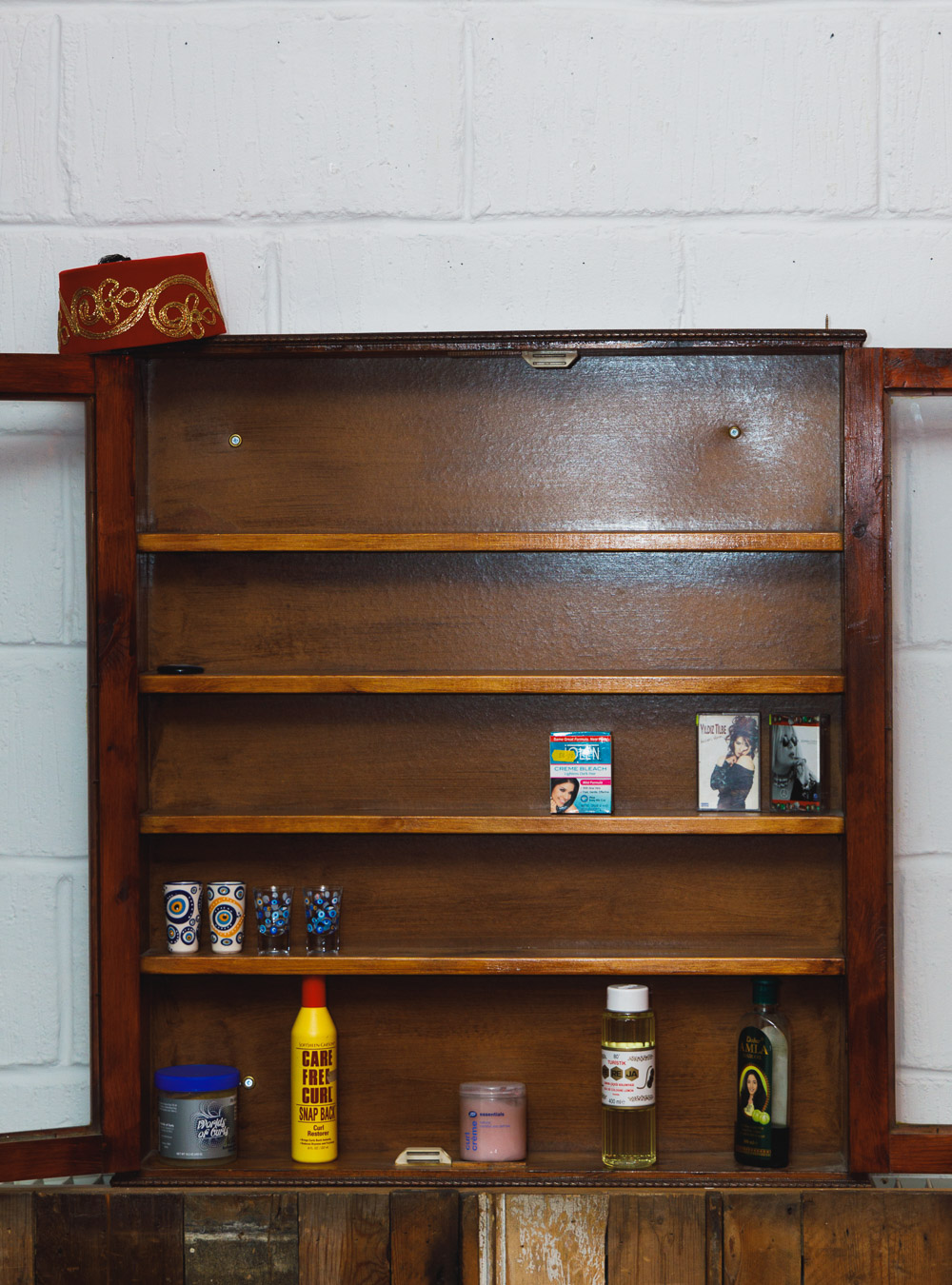

As Dania mentions during the panel, “you never want to get to the point where you’re checking boxes,” but instead work towards an ongoing praxis of ‘representation’ as an effect of the curatorial approach. The clever use of the space, down to a ‘confessions’ booth in Ugly Duck’s abandoned elevator shaft where guests can privately leave a hair secret, or the display of Jolen Creme Bleach alongside Amla Hair Oil, and even the salon-chair recreation where guests can cut off a piece of their own hair to leave behind—it all works to navigate what representation really means, and the effect of supporting a curatorial team as detailed-oriented and dedicated to the future of its community as this one is certainly felt. As Alya mentions, “the beauty of community is that they all know what it feels like.” Yas and Trina echo the sentiment: “We didn’t go on a course, or start doing it because it was making money and we could upcharge, we just said, ‘we’re cutting curly hair because we care about it.’”

But the best visual experience of the night? It’s hard to say, but the range of curl textures amongst the attendees themselves, atop tatreez patterns and keffiyehs in all colourways adorning shoulders about the room, amid cries for a Free Palestine and praise for the Palestine that is freeing us, give insight into the powerful space these creatives are working to carve out by uplifting SWANA artistry. Unabashedly “by us, for us” but deeply inviting to anyone who wants to experience and support the cultural richness on display, Talking Textures is a monument to the voices of this curly community.

Yasemin, you’ve been described as a go-to hairstylist for people from the SWANA region and her diasporic communities. What do you find to be unique about the beauty practices from these regions? How do you feel the beautification rites and standards differ from the Eurocentric ones your series hopes to deconstruct? As a hairstylist, one significant observation I’ve had is the diverse range of curl patterns, which challenges the common tendency to categorize hair types based on region. Many individuals from these communities often feel they don’t fit into the traditional categories represented in salons—they may feel uncomfortable in Caucasian salons due to unfamiliarity with their hair type, yet also feel out of place in Afro salons. This highlights the need to consider the diversity within these communities and cater to the “in-between” hair types.

We also have to contend with the influence of Western standards on beauty ideals, leading many to feel the need to alter their natural hair texture to conform. This pressure to conform stems from advertising and societal conditioning, resulting in a desire to fit into Western beauty norms by straightening hair to avoid perceived frizz or curl. My journey into the hairdressing industry (despite coming from a family of hairdressers) revealed gaps in my understanding of my own hair. This lack of knowledge led me to constantly straighten my hair and overlook its natural texture. Through my journey, I discovered a deeper appreciation for my cultural identity and heritage.

In creating the Talking Textures series, I aimed to provide representation and amplify diverse voices within the community, acknowledging shared struggles and experiences. I noticed a lack of representation for those with hair types between Afro-textured and Caucasian hair, leading many clients to feel marginalized. My series aims to bridge this gap by exploring various styling practices and their cultural significance, ultimately fostering unity and celebration within the community.

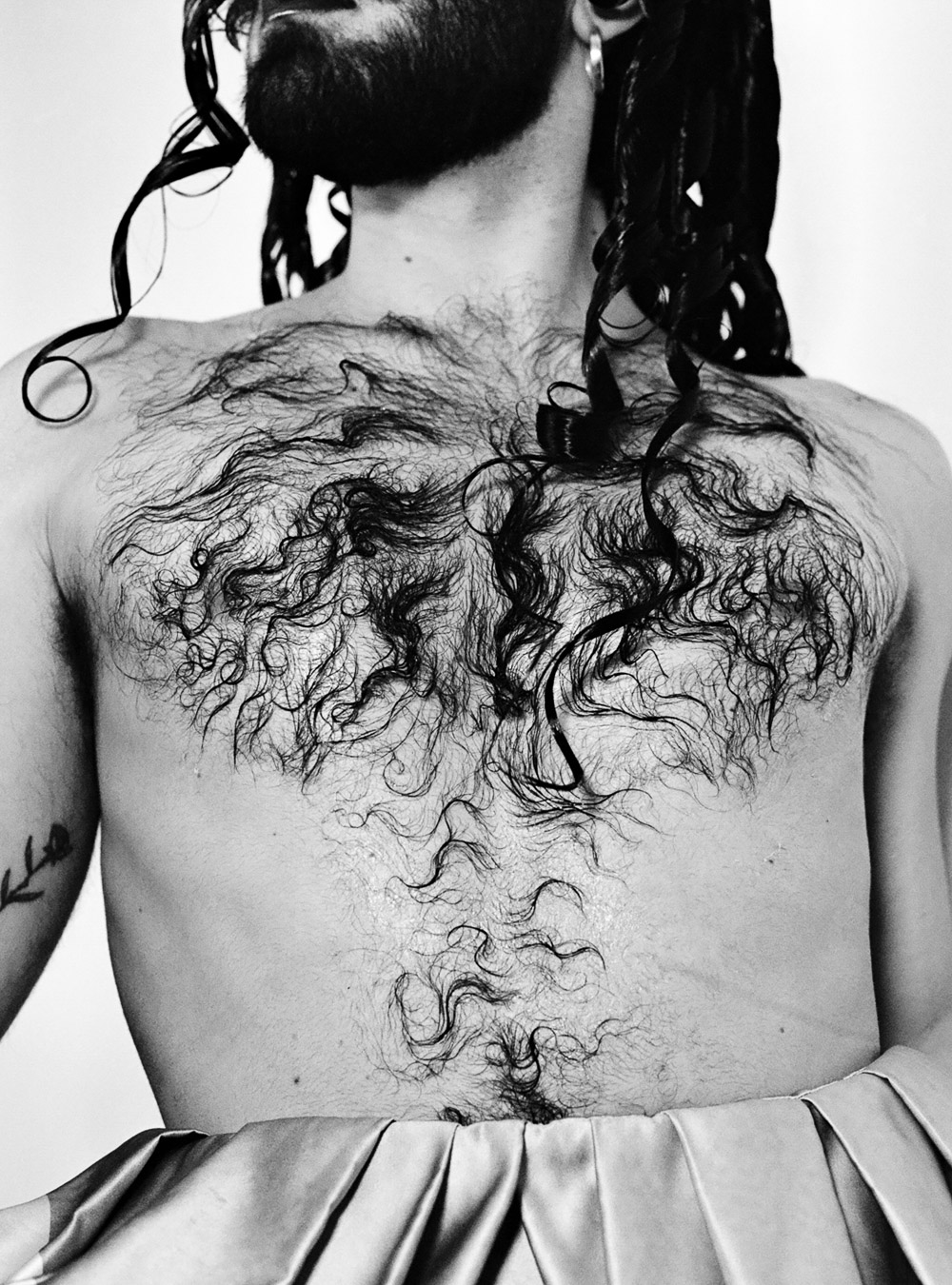

Yeliz, what approach did you take to representing these dialogues in your photographs? Your photographic practice extends beyond the hair & beauty or the editorial space—what was it like to capture hair and cultural textures? How do you feel this exhibition builds upon your other work as a photographer? In all aspects of my practice, I prioritise a comfortable environment. I work best in spaces that feel free and open, and that was especially important to me on this shoot, as hair is already such an intimate topic. It meant having a chat with the model before we took anything, or just having a bit of a joke during the shoot, so the set didn’t feel too rigid. At the end of the day, it’s daunting to be in front of a camera with 8 pairs of eyes staring back at you, so for the dialogues to really come through that relaxing atmosphere was key. How I feel about hair has fluctuated throughout my personal journey, so to be able to capture it in cultural contexts that match my own felt really special. It was also amazing just to see how much you can really do with textured hair that a lot of other editorials refuse to show in campaigns. Thankfully I was given a lot of freedom in these shoots, so even the little moments of capturing arm and leg hair was something I really loved.

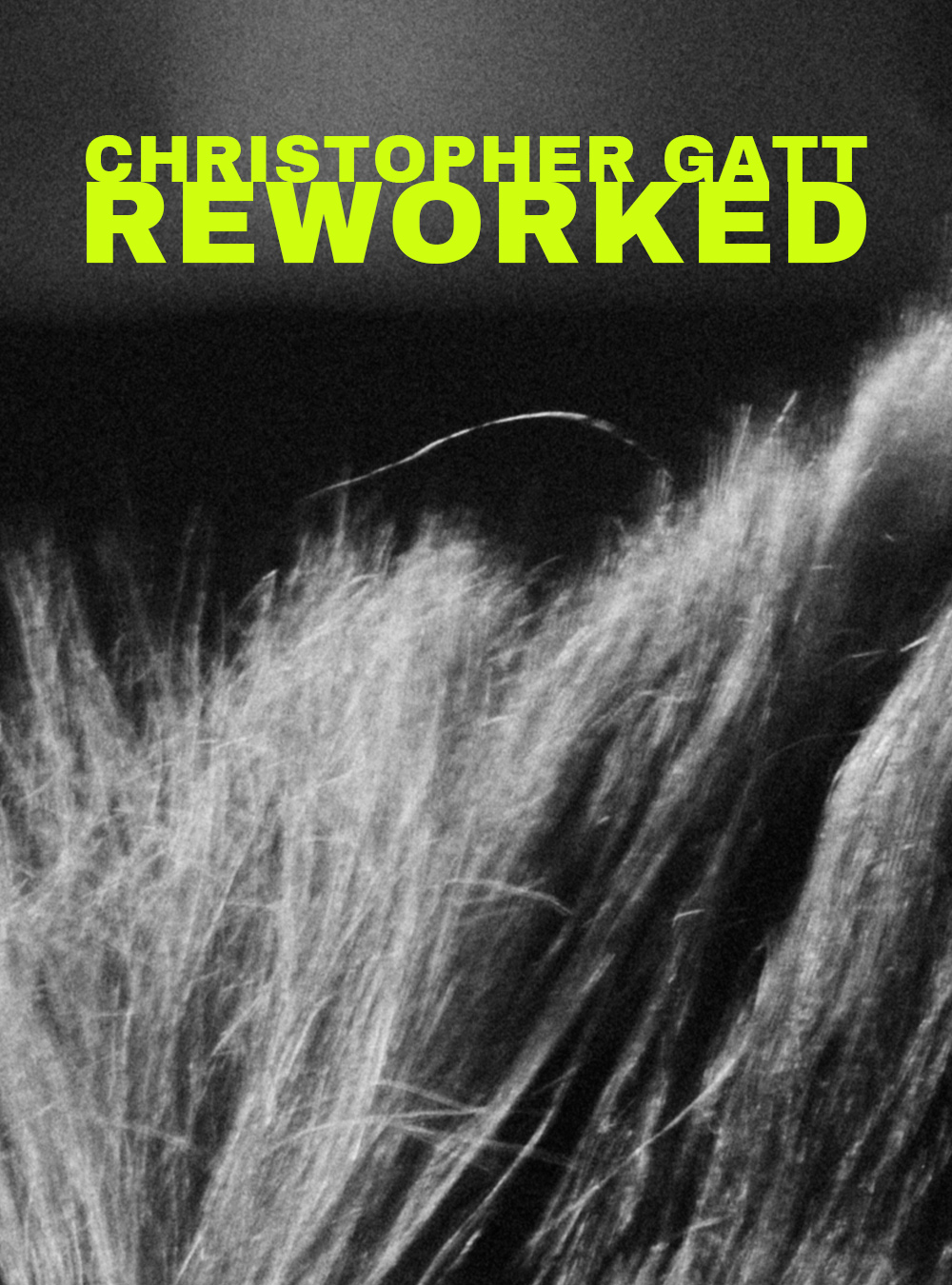

Choosing to shoot this on film as well was a huge reflection on what its meant to be about: no hiding, no shame–just raw moments of real people and real hair captured on something tangible. This body of work is quite different from the rest of my collections due to its editorial essence, so that to have in my portfolio as a photographer is always great. I like to think I have a running theme of championing different identities throughout my practice, and this definitely extends that thread within my body of work.

Dania, you’ve named creativity crucial in the process of decolonisation. You’ve also talked about “increasing the financial share of the SWANA creative community” to support that anti-colonial art process. Both strata figure into your acknowledgement of your own privilege, as a member of the diaspora with access to powerful Western institutions. How do you feel you leverage this privilege to increase attention and revenue for SWANA artists through your platform 3EIB, while not relying solely on Western audiences and their aesthetic ideals? Do these foci ever come into conflict? In a world that profits off our oppression, where governments fund genocide and genocide funds governments, creativity is crucial in the process of reimagining radically better futures for ourselves. That’s the only way we can wield our power and be a force for positive change.

My privilege lies in the fact that I’m able to navigate two cultures, speak two languages and understand two peoples. Because I am both. But my privilege is not tied anymore to my western upbringing than my Palestinian heritage. The idea that the West is more advanced is a colonial trope far from reality. The foundation of modern science, mathematics and astrology came from our communities – modernity would not exist without the advancements our ancestors made. And today, the world is waking up to the fact that we are not freeing Palestine, Palestine is freeing us!

3EIB does not rely on Western institutions or validation from the Western gaze – although we compete within this cultural landscape. We are an inclusive platform and welcome audiences from every corner of the world, but first and foremost, we are building this for our own community, and core to our practice is bridging a connection between the diaspora and those rooted in their homeland. It’s a space for us, by us, open to everyone.

Dalia, your magazine The Road to Nowhere, currently on its third issue, sharpens the focus on diaspora communities and cultures. Too often those building and living in diasporic communities and those living in their native countries are lumped as one by the powers that be on the basis of ethnicity or race, glossing over complex debates, struggles, and conversations. What conversations do you think need to be had between members of diasporic communities and those from the same region living in their native countries? What dialogues do you find commonly arising? Crucially, how do different standards and cultures of beauty present and figure into these conversations? The conversations that really need to be had are more to do with how to interact with class, gender, sexuality, and power, rather than blanketing over everyone from a certain country as being the same ‘race’, as you say. Iraqis, for example, are an extremely diverse group of people and as Iraqis in the diaspora, we need to be very aware of the differentiated privileges we hold. to speak freely and seek out creative initiatives from a western country.

I started the magazine from the basis that everyone I knew from any diaspora had this universal feeling that they didn’t belong neither here nor there. But after a few years of us having these conversations and this becoming a widely discussed phenomenon, I’m more interested now in the conversations we’re not having. I want to fill those missing gaps in our dialogues. Mainstream beauty and Eurocentric beauty standards are something so many of us in the diaspora struggled with all our lives—and still do.

I think creativity has been crucial in allowing us a space to share our common experiences, our shared struggles, and also begin to heal from the trauma of having to conform endlessly to the west’s idea of beauty. For example, I used to keratin blow dry my hair for so long until I started reading the accounts of Arab and Black women who had begun to reject the pin straight hair of noughties TV as the ideal.

Through creativity, emerging photography, writing, and more, the diaspora began to reclaim their own ancestry and heritage and labelled it as beautiful. This was such a crucial turning point in my self-reclamation journey and since transitioning back to my curls in 2020 when I first launched the magazine, I haven’t gone back to straight hair. I adore my curls.

What is your relationship to your own hair?

I am so protective over my hair, constantly trying to maintain the length, but I am genuinely starting to like my hair and appreciate it for what it is. This has been a journey throughout doing the Talking Textures series. Yasemin Hassan

It’s always been a mixed bag and my hair has changed so much in every way through the years. I’ve gone from hate to confusion to [positive] obsession with it. I love it all, from my curls to my arm hair and even my snail trail. Loving my body hair more, when I used to hate it so much growing up, is real strength and growth to me. My arm hair deserves to breathe just as much as the hair on my head, so why should I compulsively get rid of it? Yeliz Zaifoglu

My relationship with my hair is super intimate. I have shaved most of my hair in an attempt to help cope with my own trauma. Now it’s a sort of Chelsea cut. It’s been freeing, and a beautiful ever-evolving journey! Tina Khatri – Makeup Artist

It’s been a complicated relationship for years and there are still things I struggle with, but I’ve really come a long way since the days when I would chemically straighten my hair. I am really enjoying embracing the beautiful frizzy curls my ancestors have passed down to me. Dalia Aldu

It’s a complicated one because I do love my hair and am grateful for how thick and wild it is, but at the same time I rarely have it open, because it’s just so much. Either it’s in my face and in my way or it hasn’t dried quite right and looks funny, so usually I have it tied. I’m learning to appreciate and deal with it open more, and in a way I feel most free when it is open and down. Riyam Salim – Model

My relationship with my own hair is constantly a revelation. It feels like a neighbor I’ve lived next to my whole life, but only recently started saying hello to last week. ABDULISMS – Videographer

My relationship to my own hair is not great, but for opposite reasons to most people in the interview! I have very fine, straight hair – contrary to the women in my family who have thick, wavy, luscious locks. But Yasemin recently gave me a bouncy bob, which I absolutely love! Dania Arafeh

How did this confluence of collaborators come about? What has it been like to work with this specific team of women, and has it differed from your other experiences within the exhibition/ editorial space? It all happened organically, driven by everyone’s shared passion and commitment to the project. When I initially reached out for collaborators, I was so surprised by the overwhelming response from the community, eager to contribute in any way they could. Their enthusiasm and support were instrumental in bringing the project to life, and I am incredibly grateful for their involvement.

Working with this specific team of women has been a refreshing and rewarding experience.

Unlike other projects within the exhibition/editorial space, our collaboration felt natural and relaxed. Everyone involved was deeply invested in the series and understood its importance to the community. This shared understanding created a supportive and inclusive environment where each collaborator could contribute their unique insights and expertise.

The collaborative process was characterized by a sense of creative freedom and flexibility. Each team member had ownership over their respective roles, from styling to makeup, allowing for a seamless and harmonious workflow. This laid-back approach fostered creativity and innovation, resulting in a final product that truly resonated with the vision of the project.

Overall, working with this team of women has been a transformative experience, highlighting the power of collaboration and shared purpose in creating meaningful and impactful work.

There are heavy debates within the editorial sphere about ownership. Often, photographers have ownership over the images from a collaborative project, and hair and beauty creatives can often take on a secondary role when it comes to attribution and credit. Did this figure in your experience? Contrary to typical shoots where hair and beauty prep may take a secondary role, on our shoots the hair and beauty teams required and were allowed significant time—up to 3-4 hours for preparation—to ensure the hair was captured perfectly in each shot. Surprisingly, this preparation resulted in quicker shooting times than a traditional editorial approach, as we didn’t need to constantly check and adjust hair and beauty.

I’ve observed the issue of proper crediting among creatives in various projects. As both the curator and a member of the beauty team, it’s important for me to credit everyone involved, including models who often don’t receive enough recognition despite being integral to the images. They contribute significantly to the storytelling and execution of concepts.

This project owes much to the models, as their input has shaped the concepts and vision. Shooting in our salon studio at Woolf Kings Cross allowed us to create a non-corporate atmosphere conducive to creativity. The ability to wash the models’ hair afterward—a luxury not often afforded to models in editorial shoots—enhanced the overall experience. Yasemin Hassan

I think it’s important the whole team is credited when possible. I understand there are limitations, but I love knowing, for example, who was running production, or if there was an army of assistants. The credits tell their own story! But barring my name getting a cheeky mention I don’t care excessively for credit, personally. It can be common to see people fighting for various direction credits, but the people on set will always remember how much weight which crew members pulled. While crediting plays an important role in acknowledging the different voices involved, IYKYK is my approach. Tina Khatri

What stories did your contributors lend to your final exhibition, and what led you to include them? The contributors to the final exhibition of Talking Textures brought diverse and meaningful stories that enriched the project. Yeliz, a photographer I connected with through a SWANA community chat, shared her passion for capturing authenticity, which aligned perfectly with the project’s vision. Despite our differing backgrounds—Yeliz primarily worked in film photography, while I was more accustomed to digital shoots—our collaboration seamlessly combined both approaches, creating a relaxed and non-invasive environment for our models.

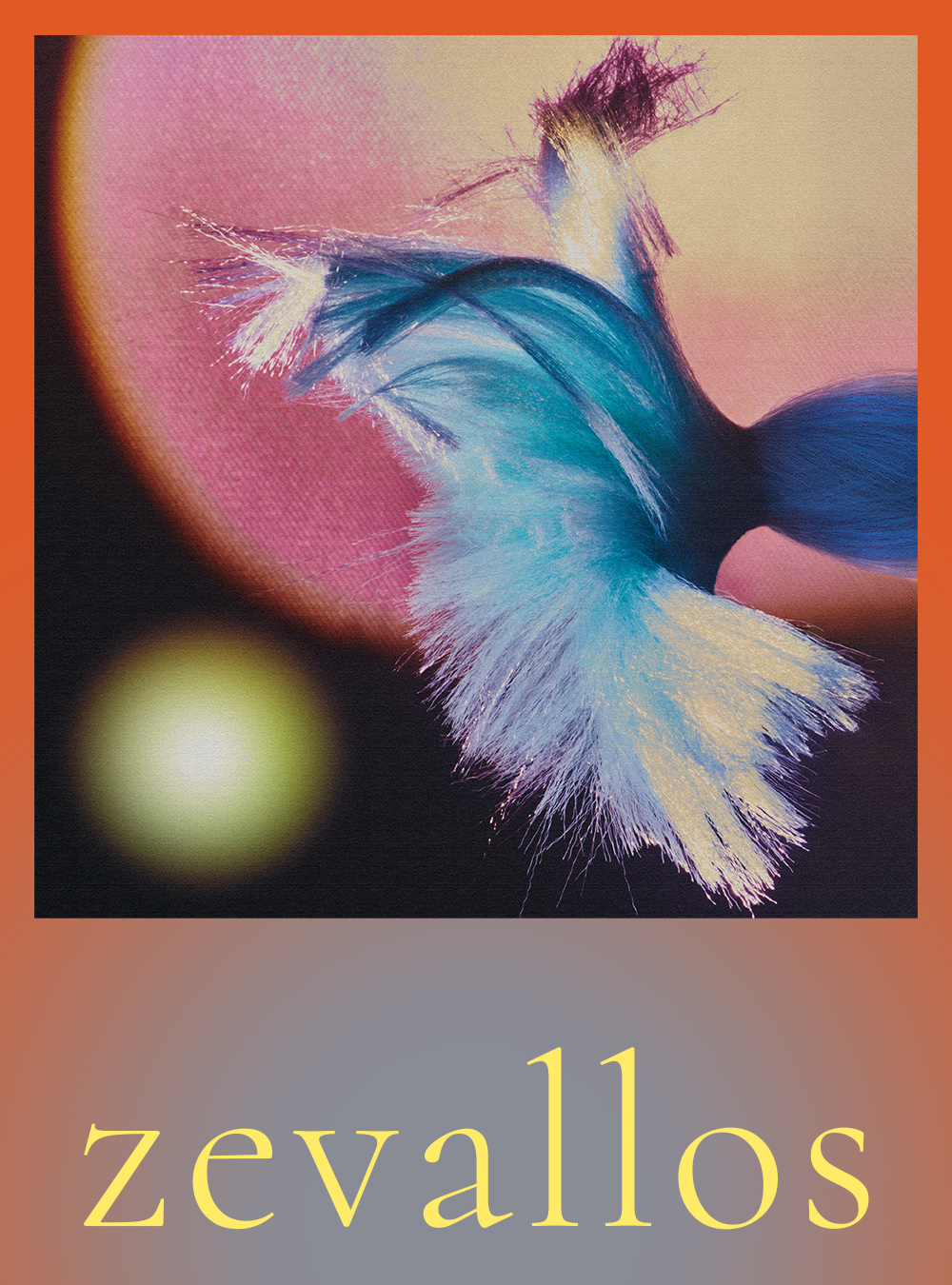

Dania Arafeh, on the brink of launching her brand 3EIB, contributed a unique perspective. Her brand reclaims the word عيب, or “shame” in Arabic. This led me to reflect on the shame we have surrounding hair within the community, and the complex struggle of challenging Eurocentric beauty standards. Her brand resonated deeply—when I saw the textures of the fabrics from the designers she represented, I know it would speak volumes to have that approach represented within Talking Textures.

The models who volunteered for the series played a crucial role, as our existing relationships allowed for open conversations about their hair journeys, informing the concepts of the shoots. For example, model Aasiya Kara’s reluctance to part with her long hair inspired the concept of “Embracing Femininity,” highlighting societal ideals of beauty and femininity from a non-traditional perspective.

After the initial shoots, I received numerous messages from individuals interested in participating, which led to the creation of “Barbershop Chat” in collaboration with ABDULISMS. This series aimed to capture the sense of community often found in barbershops, providing a platform for conversations around hair and heritage that often occur in these spaces. Yeliz and I also decided to extend the project by shooting video footage in people’s homes, delving deeper into their relationships with their hair and expanding the scope of the photo series.

Overall, the diverse contributions from these collaborators enriched the Talking Textures project, adding depth and authenticity to the exhibition. When reflecting on the whole series, I know it really couldn’t have come together without all of the contributors. I have no experience in running a team, organising a shoot, or planning an exhibition; it’s all through community connections and people reaching out, offering to help how and where they can, that this project has taken off the ground.

Why was it important for you to present these photographs alongside a panel discussion? What are the conversations you believe need to be had around the cultures represented in this series? The panel format allows for community engagement, feedback, and storytelling, fostering a space for reflection and connection with industry experts dedicated to challenging Eurocentric standards across various fields. Conversations surrounding the cultures represented in this series are vital.

We need to delve into the community’s relationship with their hair, examining how Eurocentric advertising has influenced their hair care practices and perceptions. As hairdressers, we must explore ways to accommodate all hair types and promote inclusivity within our industry. This includes advocating for changes in the education system to ensure comprehensive training on textured hair and discussing strategies for decolonizing hair standards.

Ultimately, our goal with this series is to ignite dialogue, amplify diverse voices, and showcase the skills and contributions of collaborators who are actively challenging norms within our region.

Direction, Curation, + Lead Hair: Yasemin Hassan

Photography: Yeliz Zaifoglu

Videography: ABDULISMS

Makeup: Tina Khatri

Styling: Dania Arafeh with 3EIB

Hair Assistants: Matthew Tharp, Shaun Birmingham, + Amy Clarke

Contributors: Ali Nasreldin, Jalal Sajan, Khadija El Kharroubi, Eman Alali, Adam Ghellache, Peyam Zangana, Alex Shabib Hoggett, Tuka Mohammed, Dalia Al-Dujaili, Micheala Mousicous, Sheniz Hassan, Jenna Anne Nathan, Riyam Salim, Aasiya Kara, Trina, Alya Mooro, berkeğim, Rama Alcoutlabi, ZAYTOONA, Ayshe-Mira Yashin, + Tahini Molasses

Designers: Zoubida, MEHDI, MOMS, Nöl Collective, Isis Dünya, Ziyad Buainain, Leena Sobeih Studio, Studios Abz, HYPEPEACE, + merxury.myriad

Graphic Design: Jake Richardson

Event Photography: Esteshhad Quisay + Amelia Sonsino

Special Thanks: Ugly Duck + Woolf Kings X

Words + Interview: Hasadri Freeman

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR