- The Hair Portraits

- The Hair Portraits

- The Hair Portraits

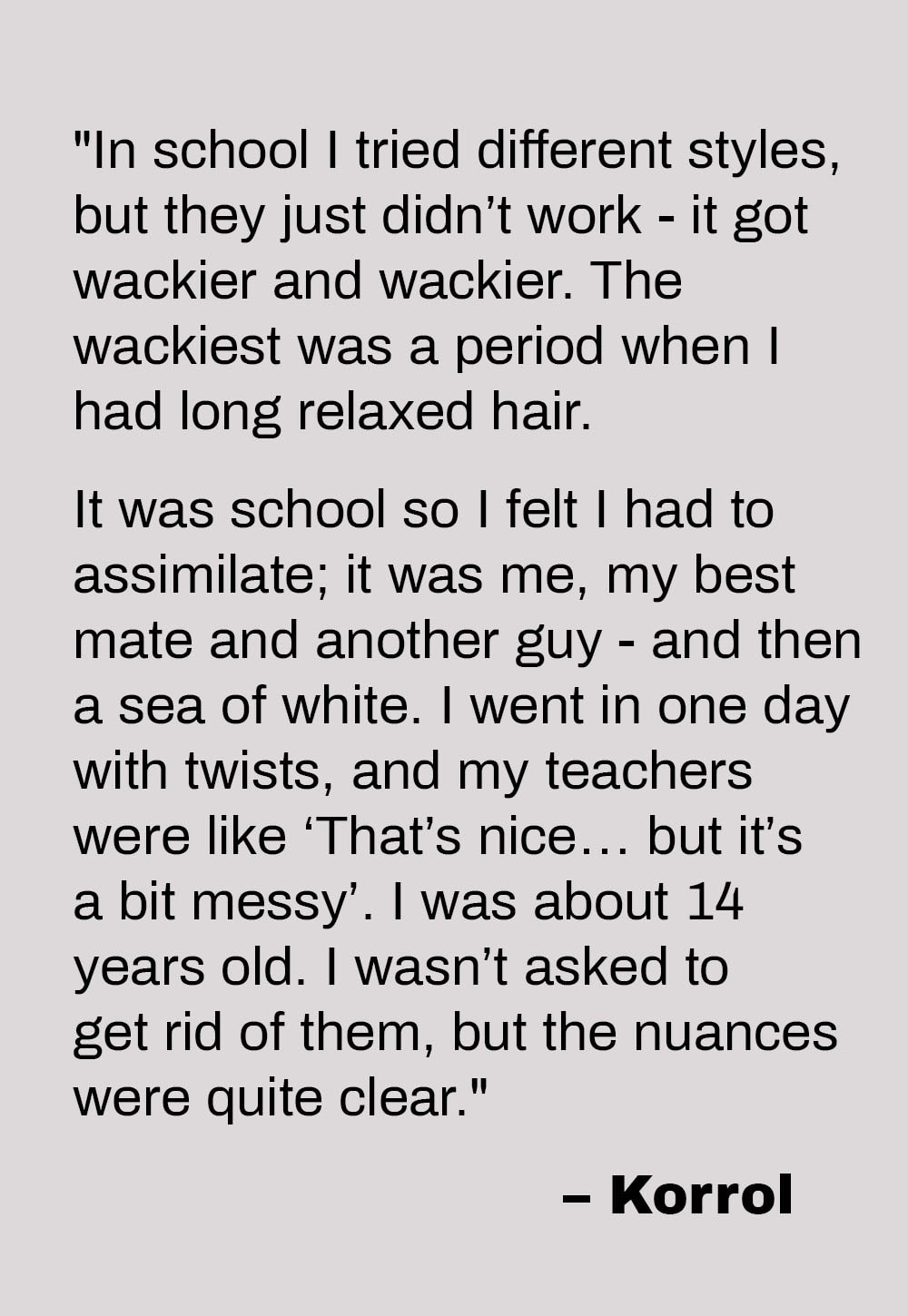

PEOPLE: In her photography series The Hair Portraits, Clara Watt interviews her subjects to document personal insights into what it means to have black hair today

Photography + Interviews: Clara Watt

Clara Watt is a London-based documentary photographer. Originally from Switzerland, Canada and Senegal, she started #theHAIRportraits to highlight the wide spectrum of black hair, and to document the experiences of men, women, and non-binary people navigating the politics of living with black hair. It’s Watt’s hope that these portraits spark conversations about long-standing Eurocentric beauty standards, but above all, that it gives some of you the confidence to explore your own relationship with your hair.

“My hair makes me feel like a queen, my afro is my crown.

I haven’t always liked my hair. It has taken me many years to get to a place where I accept my natural hair for what it is. I think it was mainly because I didn’t know how to handle it. I used to always try to straighten my hair to fit in with the other girls at school so I guess you could say I used to wish I had straight hair. I didn’t like standing out. After many years of growth, understanding and acceptance I now embrace my natural afro hair.

I wish people would understand that black hair is political. We are judged constantly by the way we choose to wear our hair – at school, in the workplace etc. People make unnecessary comments and I wish they’d just keep quiet instead. Don’t get me wrong, I love a compliment but leave it at that.

My hair definitely represents my identity. It’s a part of who I am. I wrote a whole play about how I struggled with my hair and how accepting my afro hair led me to accept and understand my identity.”

– Lekhani

- The Hair Portraits

- The Hair Portraits

- The Hair Portraits

- The Hair Portraits

“I used to always straighten my hair. I can’t believe that I was putting in so much time and effort to essentially ‘kill’ my hair. Because I straightened it for so long, I didn’t even know my hair’s natural state, so I couldn’t see how it could look beautiful. Looking back now, I can’t see myself ever going back – I love my natural hair. It takes up space, and I’m making this space my own.

Shaving my head was a bold move made at 2 am on a Monday morning – of course, I was slightly apprehensive. Will I look like an egg? Does my head have a weird shape? Will I regret it? The answer is no to all of these questions. I feel like this hairstyle suits me better than any other.

I identify as non-binary/ genderqueer/ gender fluid… whatever you want to call it. I loved my long hair but I felt uncomfortable being immediately classed as ‘feminine’. I feel more like myself when I adopt an androgynous aesthetic… and hair grows back!”

– Ari

“I grew my afro out for about a year and a half. One day, my school in Costa Rica did a hair donation for Cancer Research, where they were auctioning off people’s hair. Those that could donate their hair would, but I couldn’t donate mine. In my case, the person who bid the highest got to shave my hair off. I had two of my ex-girlfriends bidding against each other, and I ended up getting the second highest bid in the school.

In Ghana, a lot of people aspire to have straighter hair and loser curls, instead of kinky hair. I feel I had ‘privileged’ hair. I was never made to feel like I wanted to change my hair, especially as a guy. I know girls had a different experience. A lot of half-Ghanaian, half-Japanese girls want to have really straight hair, being heavily influenced by Anime culture, especially when everyone in Japan has extremely straight hair.

I didn’t grow up doing a lot of hair care stuff. My mom’s Japanese, she didn’t know what to do with my hair. My dad’s Ghanaian. So I never learned all that stuff. With dreadlocks, they’re gonna do what they’re gonna do. Let them be. Take care of them, but you can’t be too bothered about how you want them to look. I’ve started to get more into dreadlock philosophy and self-love. Appreciation for being yourself. I feel my dreads have made me feel more free, so they match my personality.”

– Pele

“Even my own dad, who’s white, who has four mixed race children, doesn’t understand the political side of black hair. He’s very open and understanding, and he’s willing to listen, but it just doesn’t hit home. Hair is something that’s so overlooked — people don’t see it as something that’s deep but for black people it very much is, because it’s our reality.

My hair was relaxed for me without me knowing. I was dropped off at the hairdressers by my mom, and usually she would stay with me but this time she had to run some errands so she left me there. The women were telling me how difficult my hair was to manage, and suggested a treatment that would make it nice and slick. I saw the relaxer box and didn’t know what it was, I was 11 years old. I said “Yeah I want this, the girl on the package looks cute!”. It was a terrible experience, my scalp was burning. They washed it out, and I was like ‘Wait, my hair doesn’t look like the girl on the pack’ and they said ‘Of course not, you have to style it’. I felt scammed. My mom came back and she said ‘oh, did you relax her hair?’ And she looked at me asking if I had wanted that, but I was 11 years old. I didn’t know what I wanted.

It’s weird that the hair on my head is political, but it is, and it shouldn’t be. Race is political. There are certain hair types that are deemed more acceptable than others. In certain professions you can’t have braids, you have have your natural fro out. In school they told me I couldn’t have my natural hair out. I had to have it back. I couldn’t be bothered to argue, but if it was me now, it’d be a different story.”

– Ester

- Clara Watt

- Clara Watt

- Clara Watt

- Clara Watt

“I once had a weave… it didn’t go well. My scalp couldn’t breathe. I had it as a bob cut, so I looked like a ‘Karen’. I thought ‘Well I paid for it, I may as well wear it’, but I remember my mom coming after me with a pair of scissors going ‘We’re cutting it out, it’s terrible!’

My mother’s white, and she loves my hair when it’s fluffy. She used to puff it up and stick a bow in front of it. She thought it was amazing. I looked like a Bishon Frise. Everyone wanted to touch it, because they had never seen it before, since it was just the three of us in school. I’m used to being different and the only black person in a crowd.

I can make my curls more defined, it just takes so long and requires me twirling each curl around my finger. When I was younger my mom would do it for me, but it had to be done in the morning, because if I slept on it, it would flatten the curls. So I remember waking up at the crack of dawn to curl each strand on my head. People wake up that early to do their make-up for the day, I’d have to do it to not look like a pom-pom.

The last place I worked, this girl from Guadeloupe was like “Oh! now I have someone to speak to about hair!” and I was like “I don’t know anything about hair”. She thought because I was black that I should know everything there is to know about how to manage black hair. I was raised by a white woman.”

– Amelia

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR