PEOPLE: INFRINGE meets the late artist’s son and visits his former studio in Rio de Janeiro

Words: Katharina Lina

Art: Tunga

Photography: Panos Damaskinidis, Tunga’s Archive provided by Instituto Tunga

Video: Antonio Celotto

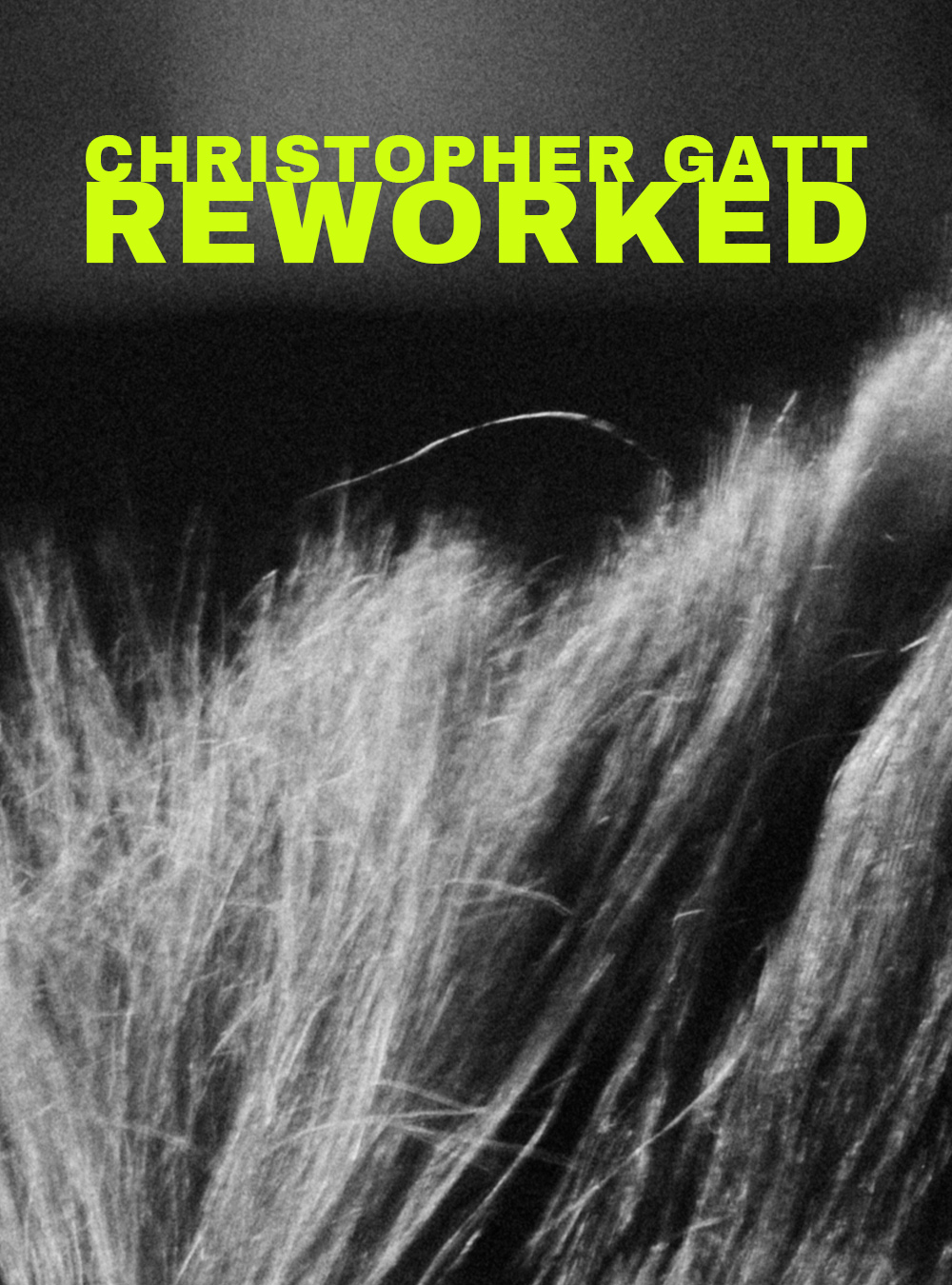

Tunga was one of Brazil’s most cherished artists, known for his surreal and alchemistic sculptures, installations and performances that often involved unorthodox material combinations like teeth, bones, and hair.

In 2005, he displayed a hanging installation of hammocks, skulls and hair in the Louvre in Paris, which was the museum’s first ever contemporary art installation. “Most of his life he worked from home” Antônio Mourão, Tunga’s son told INFRINGE. “He used to say that the hammock was his office. He would stay in the hammock swinging and swinging, and everyone thought that he was being lazy. But actually he was having these amazing ideas for sculptures, performances, and drawings.”

“It’s always funny when people come to me and say ‘I was a twin in the 80s’ or ‘I was a twin last year’”

Tunga, also known as Antônio José de Barros de Carvalho e Melo Mourão was born in 1952 to the writer and poet Gerardo Melo Mourão and social activist Léa Barros. He had initially studied to become an architect when he decided to go down a more artistic path — although his structural and spatial understanding continued to be put into use in his work.

One of his most recognisable works Capillary Xiphopagus Among Us is a performance piece of two twins who are conjoined by their hair. “Capillary Xiphopagus is my favourite work of Tunga’s” visual artist and performer Andressa Cantergiani tells us enthusiastically. “The dreamlike and psychedelic narrative of the twins, this myth that the twins were born fused at the hair. It is not the belly bottom, it’s the hair. It is this umbilical idea of hair. The hair comes from a place that is connected to the universe and to the earth. It loses its human aspect and assumes a mythological status.” Tunga’s son Mourão recalls meeting multiple sets of twins over the years: “He first showed this performance in the early 80s. It’s interesting because there have been several twins during my dad’s career. So today there are twins nearly in their 50s and then there are twins that have just performed at the Tate Modern in London. It’s always funny when people come to me and say ‘I was a twin in the 80s’ or ‘I was a twin last year.’”

Some of Tunga’s favourite recurring media and motifs were organic matter such as teeth and hair. Hair is not static, it carries and grows out of its own history. Tunga’s former assistant and the production director Instituto Tunga Fernando Sant’Anna elaborates: “Hair has to be modified and cut, as it grows all the time. For us humans, and for our rational lifestyles, we deal with something that never stops growing — it’s a completely irrational thing.” Sant’Anna goes on to tell a chilling story about a body that had been dug up, and to everyone’s shock all the flesh had been eaten or decomposed except for the scalp with all the hair still attached. “It’s a fantastic story. And it fits like a glove in this universe of Tunga.”

Teeth were another aspect of Tunga’s fascination. Mourão remembers his father taking an interest in collecting his milk teeth. “He was always looking for new ideas to do with teeth. I had started losing my baby teeth and he wanted to collect my teeth to use them in his artworks. Both hair and teeth are memorable moments in my childhood with him.” The transition from milk teeth to adult teeth holds a similar significance to Tunga’s interest in organic human aspects that undergo drastic change, albeit for a more rational reason than ever-growing hair. “Teeth and nails have other peculiarities. They’re our only parts of our entire surface which are rigid, because the rest of our skin is soft when coming into contact with things that are too hot or too hard; so we can only use nails or teeth. So we started to develop tools, to even this deficiency.”

A giant tuft of hair made out of lead could be seen as one of those tools to even the body’s deficiency in rigidity, or to compensate for Tunga’s perceived irrationality of hair. But as per usual in the art scene, the viewer is welcomed to come to their own conclusions when looking at the work. “One one hand, my dad’s work is very simple, in the sense that you can be delighted, or not, when you see his work. On the other hand, it is also very complex because there are all these thoughts behind it, usually involving psychoanalyses, mathematics, physics, chemistry.” Mourão explains. “Now and then I used to ask him: ‘Dad, what does it mean? Why this?’ And he would answer teasing me: ‘I don’t know. Help me. I also want to understand what I have done.’ Of course he had an explanation for all of it. But I think what he wanted most was that people could develop their own thoughts about what he had done. And perhaps then he would come to new conclusions that he had not seen before.”

“Hair has to be modified and cut, as it grows all the time — it's a completely irrational thing”

This idea of making your own sense of the things that you see, whether it was his work, or anything you’re confronted with in the world, it was important to Tunga to have your own thoughts and conclusions, and to speak them freely without being afraid to say the wrong thing. “Everything is stagnant” Sant’Anna explains passionately. “Institutions, the audience, the press, the academy, all stagnant, stagnant, stagnant. It’s just that we don’t perceive it. Tunga studied things like physics, psychology and mixed these topics with themes like astrology, or anything that got onto his radar. He combined topics and provoked thought without being an expert and created new conversations. The problem in our society now is that we have stopped talking about things we’re not experts on. But if I were to only talk about the things I studied, I will always be under the shadow of the institution that taught me.”

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR