ART + CULTURE: The British Museum’s extraordinary exhibition shines a light onto the Victorians’ most beloved accessory trend

Words: Katharina Lina

Special Thanks: Judy Rudoe

Photography & Jewellery Captions: Courtesy of British Museum

What was initially thought to be a first display of some of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert’s rare etching prints amounted to an even more intimate perspective into the Victorian life when the British Museum received a sophisticated collection of Victorian hair jewellery from Ann Louise Luthi, author of Sentimental Jewellery (1998).

Most of us have heard of keeping a lock of hair of a loved one inside a locket, but during the Victorian era, skilled artisans took the concept of hair jewellery to the next level. When her beloved husband Prince Albert died, Queen Victoria famously mourned for a prolonged time, created a mourning culture and popularised hair jewellery. And although the queen carried locks of Albert’s hair in her pendants while she grieved, her interest in hair as a keepsake turned out to be equally about love as death. She adored exchanging freshly cut hair with members of her family on birthdays and anniversaries, as hair symbolised a corporeal presence of the beloved and was used for friendship tokens as much as for memorialising the dead.

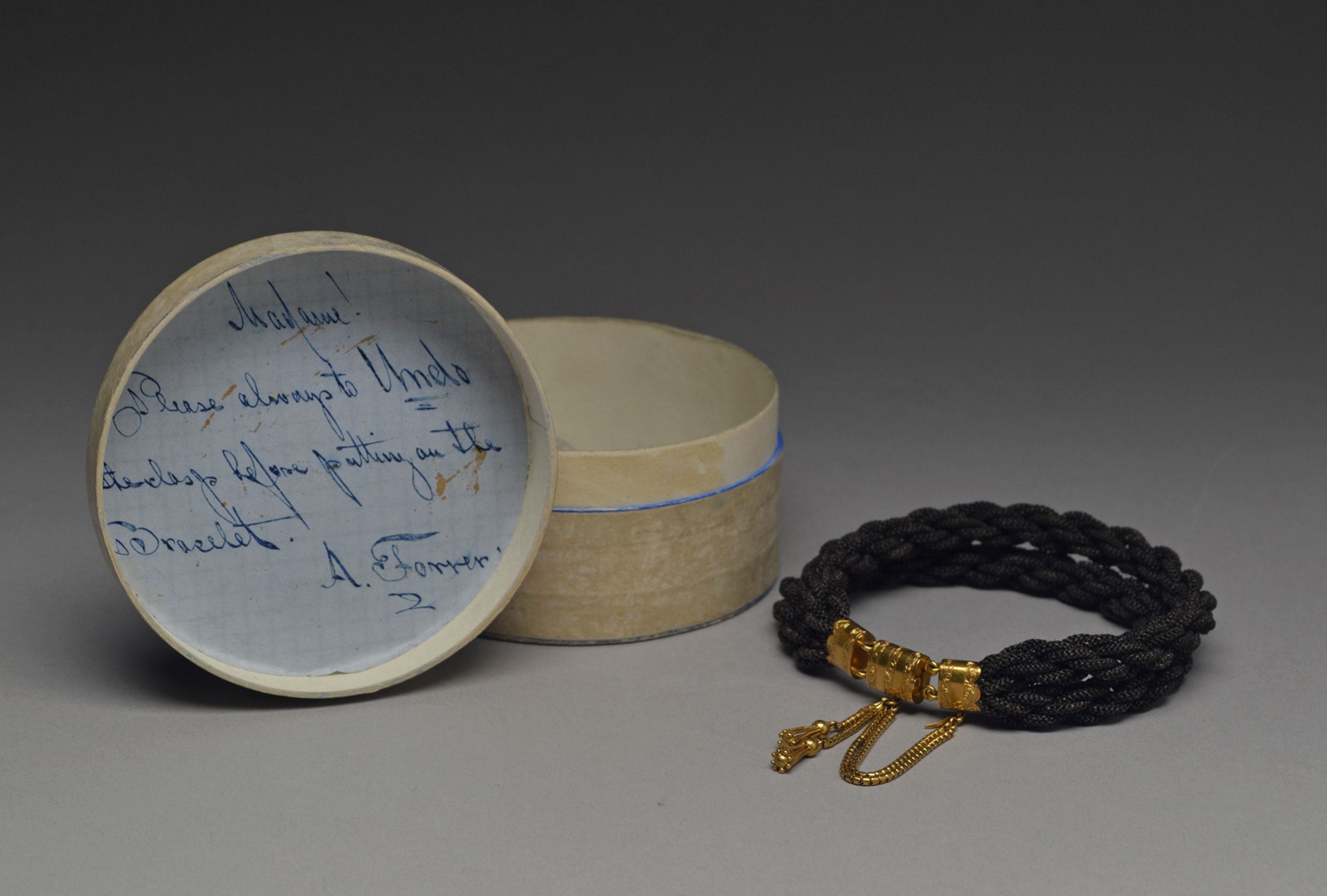

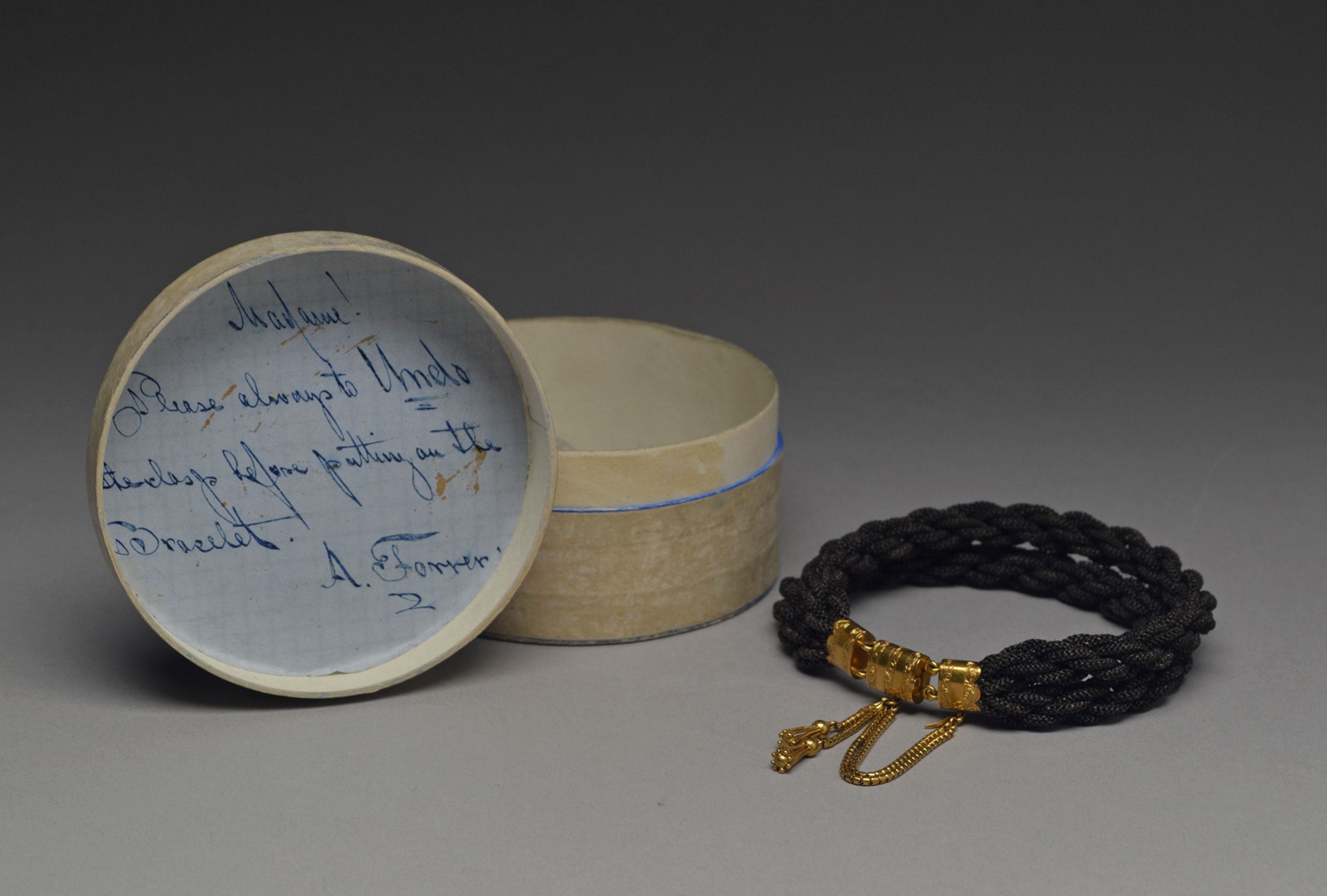

As Judy Rudoe, a specialist in the history of jewellery and also the curator of the Woven In Hair exhibition tells me over the phone, since the 17th century, hair of the deceased had been worn in lockets as part of a mourning process. But it wasn’t until the 1820s and ‘30s, and thanks to the queen’s infatuation with hair memorabilia, that hair jewellery became an in-demand fashion trend. Smart jewellers quickly picked up weaving techniques and developed ways to utilise hair as strings or chords, making jewellery that was made of hair rather than jewellery that carried hair in a locket. The designs started to become absolutely extraordinary as hair was braided and woven into intertwining textures and three-dimensional lace sculptures.

Contrary to the notion that hair jewellery is ‘creepy’ because it involves cutting hair from a dead person, it was actually impossible to weave hair from a head that wasn’t alive anymore because it would lose its flexibility almost instantly. For any jewellery that was made of hair, as opposed to a locket that carried hair inside, the hair had to come from a living and breathing body; so it clearly wasn’t as macabre a practice as it is sometimes made out to be.

As the hair jewellery trend manifested and the pressure in turnover time increased, some hair artists would, unbeknownst to the client, use artificial hair when the given loved one’s hair was insufficient in amount, or difficult to work with in texture. To avoid these kinds of schemes, women started braiding and weaving the hair jewellery at home.

Ladies’ magazines started publishing step-by-step manuals and patterns for homemade hair jewellery and women wove their own hair designs only bringing it to a jeweller or hair artist to get the finishing gold clasps inserted. But as Rudoe explains to me: “It became so much of a trend, emotional attachment or not, that those who really wanted it weren’t necessarily concerned about whose hair it was.” And since many of the hair artists were actually wig makers who created hair jewellery as a side hustle, access to shinier or sturdier hair was a given.

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR

- ANTHROPOLOGY OF HAIR